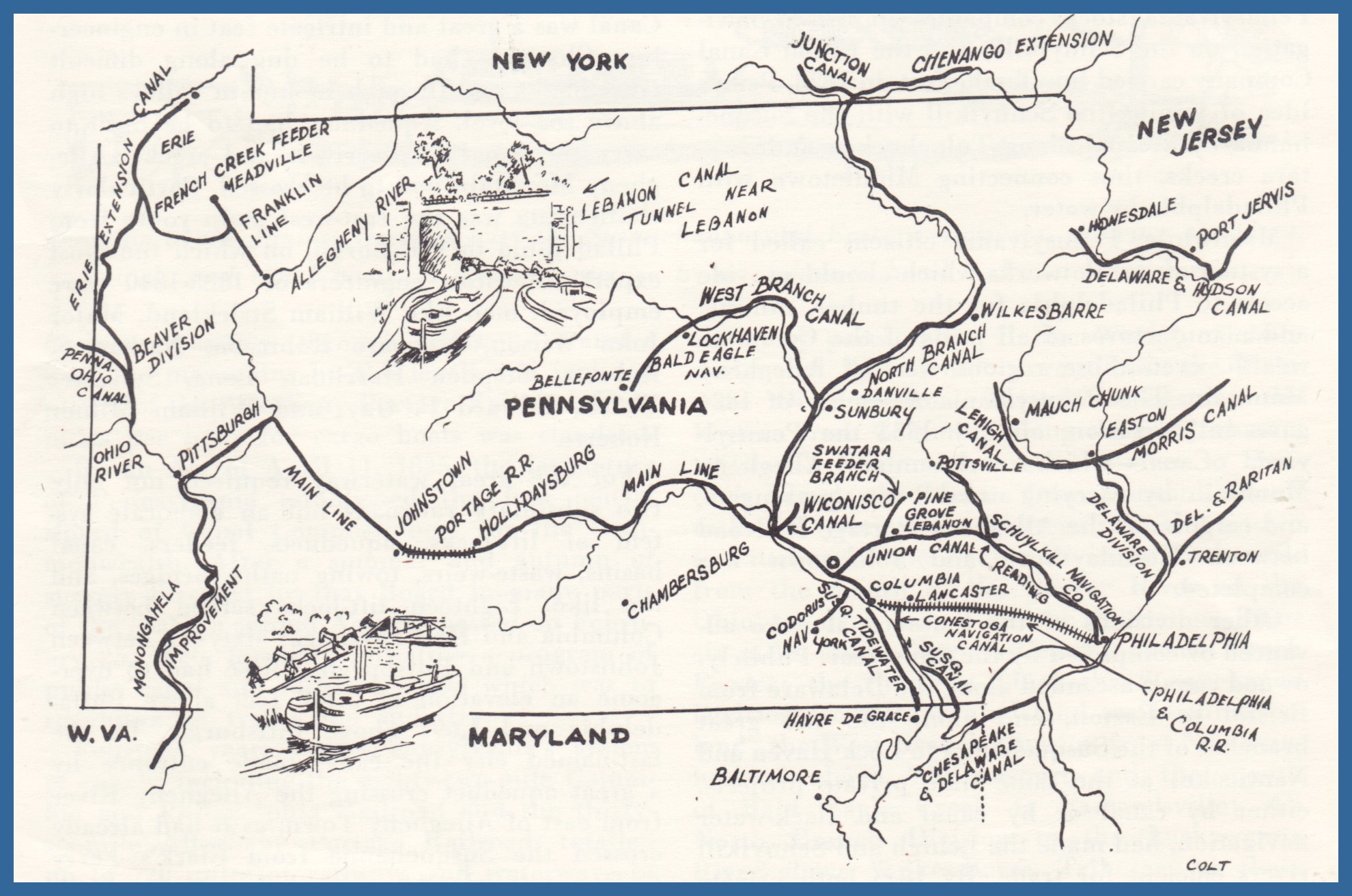

In a four page pamphlet published in 1969 by the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission, a brief story of the history of Pennsylvania canal system is told. The above map is from that publication, and shows how much of the Commonwealth’s canal system used the trajectory of the Susquehanna River in the mid-state, although the location of one of the feeders, the Wiconisco Canal, appears to be slightly off as to location.

On the first page of the pamphlet, the author acknowledges that nature itself played a role on the development of the canals in that the rivers provided a “piercing” of the mountains. While the first canal was proposed by William Penn as early as 1690, it was not until more than a century later that a canal was actually built. This canal, the Conewego, was built in 1797 on the west bank of the Susquehanna River just below York Haven to allow boats to avoid the rapids of the Conewego Falls.

New York State was next to get into the canal business with the famed Erie Canal built between 1817 and 1825, and thereafter, with the urging of Pennsylvania citizens to call for “public works” that would enable the products of the interior to get to all parts of the Commonwealth, a boom in canal construction took place. This boom lasted slightly more than 25 years, and by the mid 1850s, the canals were in full-blown competition with corporate railroads. Eventually, the railroads purchased the canals from the state and put most of them out of business.

The Wiconisco Canal was built as a feeder canal to connect the Lykens Valley and the Wiconisco Creek with the so-called Eastern Division of the Pennsylvania canal system. The Wiconisco Canal meandered down the east bank of the Susquehanna River down to Clark’s Ferry Dam, Dauphin County. If the entire Eastern Division had been completed as planned, a route of 934 miles of navigable waterway would have resulted in an easily traversed route from the mid-state to the ocean, and from the Susquehanna River to the Schuylkill and Delaware Rivers.

The pamphlet concludes with the following on the demise of the system:

Canal operation ceased earliest in western Pennsylvania. East of the Alleghenies the canals in private possession were rather more prosperous. The Pennsylvania Canal Company maintained most of its waterways until 1901. After the floods of 1889, it is true, use of the old Juniata Division became impracticable except for a few mile above Duncan’s Island; and, after the flood of 1894 hopelessly damaged the Susquehanna and Tidewater Canal, cargoes could no longer be “boated” onwards from the Eastern Division to Atlantic ports. The Union Canal had closed ten years earlier in 1884.

However, from the days of the Civil War into the twentieth century, the canals of eastern Pennsylvania prospered from the movement of coal. The Schuylkill Navigation Company operated until 1922, the Lehigh Coal and Navigation Company, embracing its Lehigh and Delaware canals, until 1931.

Perhaps the most notable of Pennsylvania canal achievements was the “”boating” until 1894 of millions of tons of anthracite coal annually from the Nanticoke on the North Branch of the Susquehanna to Jersey City and New York.

These boats pursued their leisurely way from lock to lock, over aqueducts, and along towing paths and towing path bridges, frequently with the captains’ families aboard. Mules drew them on their long inland passage, but side-wheelers and steam tugs towed them on the rivers. They passed by Northumberland, Clark’s Ferry, Middletown, Wrightsville, and Havre de Grace to the Chesapeake and Delaware Canal. Then they went up the Delaware River to Philadelphia, or further by way of the Delaware and Raritan Canal in New Jersey past New Brunswick and Perth Amboy to the Hudson River and wharves of New York.

The days of canal transportation in Pennsylvania are over. Historical markers still point out the traces of former canal beds, ruined locks, and other reminders of the canal age….

___________________________

Corrections and additional information should be added as comments to this post.