This story was previously posted on The Civil War Blog on 1 July 2016 and then updated on 19 July 2017:

__________________________________

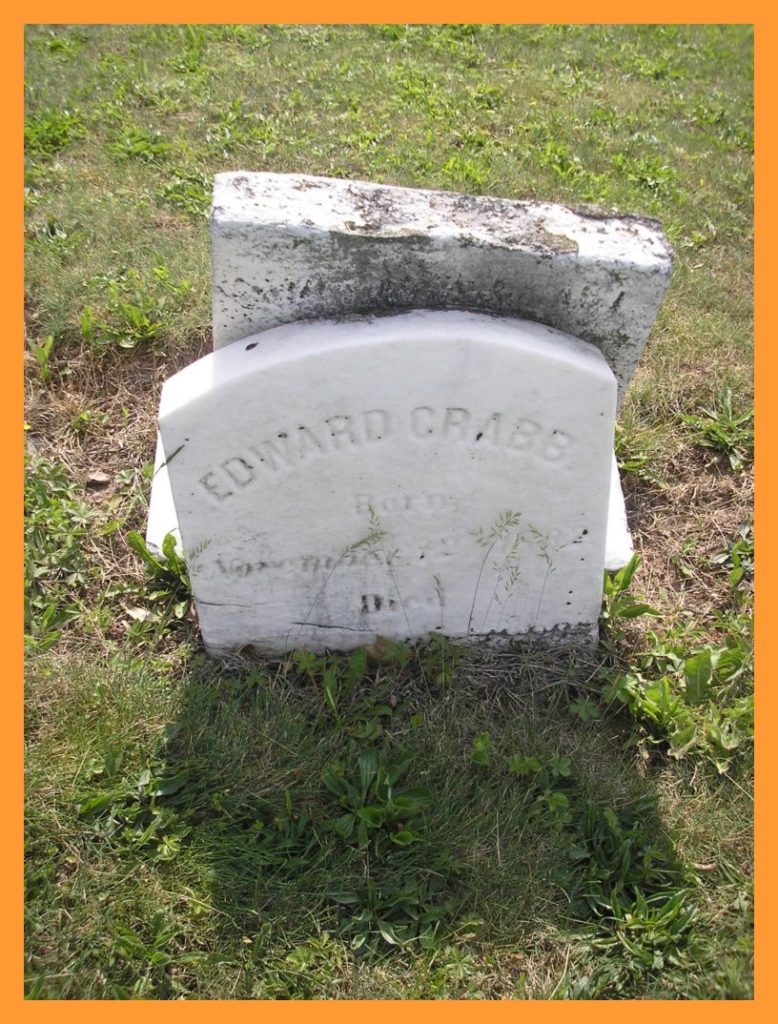

Another Memorial Day has gone by and the grave of Edward Crabb, an African American Civil War soldier buried in Gratz Union Cemetery, continues to be un-decorated [no G.A.R.-Star-Flag-Holder and Flag]. In addition to being un-decorated, the Crabb family plot is one of the worst maintained in a cemetery which is known for its manicured grave sites and magnificent views of the Mahantongo Mountains to the north. In the family plot photograph above, taken on Memorial Day 2016, two of the stones are broken and one is tipped so that it can not be easily read. The broken stone at the left is for Lydian [Schoffstall] Crabb, later Witman, who was married to Henry Crabb (1817-1856), brother of Edward Crabb, and was the mother of a Civil War soldier, William P. Crabb.

The stone at the right, shown below in detail (also taken on Memorial Day 2016), is for Civil War soldier Edward Crabb.

These broken stones have been evident for many years. Could it be that these grave sites were desecrated by vandals who knew that this was an African American burial plot?

It is not surprising that this has happened in a community that for at least the last 20 years has denied that this was an African American grave site.

Following a history of the honorable record of this Civil War veteran.

Edward Crabb was born on 12 November 1832 in Gratz. He was the son of Peter Crabb (1787-1860), an African American who was one of the first settlers in Gratz shortly after the town was laid out by Simon Gratz in the early part of the 19th Century. The descendants of Peter Crabb were numerous. By the time of the Civil War, Gratz had one of the highest populations of free Blacks in the Lykens Valley area. Some of the sons and daughters of Peter Crabb married into the White families of the area, but others chose to marry into the numerous other African American families in a broader region – to Line Mountain in the north and to Peter’s Mountain in the south. Most of the descendants who married White ended up passing, while those who married Black were usually unable to do so. Edward Crabb was one of those who married Black and did not pass.

William P. Crabb, the Civil War soldier mentioned in the first paragraph of this blog post, was the grandson of Peter Crabb, the African American pioneer settler of Gratz, because his mother was White and he was light-skinned enough to pass, he and his descendants chose to refer to themselves as White.

In 1850, Edward Crabb, a laborer, is found in the household of Samuel Umholtz, a farmer of Lykens Township. In that census, he was listed as mulatto.

By 1863, Edward had learned the craft of shoemaking and registered twice for the Civil War draft – once in Coal Township, Northumberland County, and once in Lykens Township, Dauphin County. In both cases, he was listed as colored.

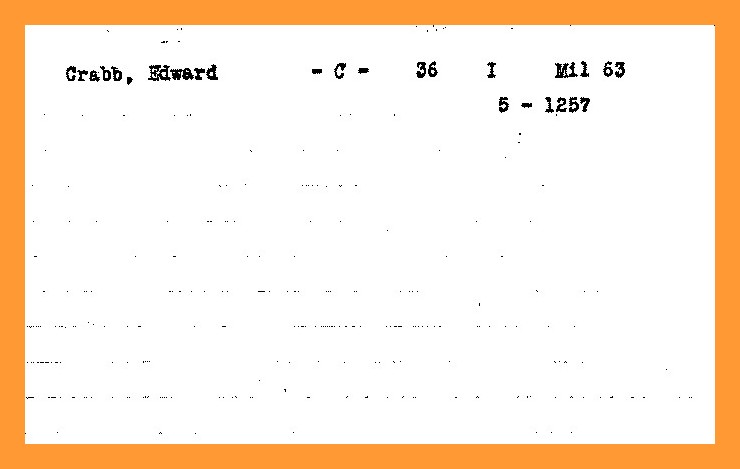

A few days after the draft registration, Edward Crabb was in Harrisburg with his company and regiment, ready to serve for the Emergency of 1863, Lee’s invasion of Pennsylvania. The 36th Pennsylvania Infantry Militia, Company C, was composed primarily of men from Lykens Township and Gratz and served from 4 July 1863 through 11 August 1863. Prior to the Civil War, both Edward Crabb and his brother John Peter Crabb were listed among the members of the Gratztown Militia, a home guard unit that was organized under the Second Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. It was this Gratztown Militia that became Company C. Edward and his brother John Peter were the only known African Americans in the company that consisted of about 76 men. It is important to note here that these emergency forces were under Pennsylvania command, not Federal command and therefore there were no racial restrictions on the service of African Americans. Most of the men knew each other from their “home guard” militia service and no evidence has been seen to suggest that there was any discrimination against the brothers who served in Company C. Note: The Pennsylvania Veterans’ File Card, shown above, is from the Pennsylvania Archives.

The brief history of this militia regiment in the war is recorded in Bates, Volume 5, page 1257, Pennsylvania’s official Civil War history, and therein is included the name of Edward Crabb. The responsibilities of the 36th Pennsylvania Infantry Militia included the cleaning up of the Gettysburg Battlefield, which was hazardous due to the large number of decomposing bodies that needed to be properly buried as well as the un-exploded shells remaining there. Bates reports specifically on the activity of the 36th Pennsylvania Infantry Militia beginning on page 1228 of Volume 5:

So rapid were the movements of the armies, and so soon after call for the militia was made the decisive battle fought, that the men had scarcely arrived in camp [at Harrisburg], and been organized, before the danger was past….

The militia was, however, held for some time after this, and was employed on various duty. The Thirty-Sixth Regiment was sent to Gettysburg, and its commanding officer, Colonel H. C. Alleman, was made Military Governor of the district, embracing the battle-ground. It was engaged in gathering in the wounded and stragglers from both armies, in collecting the debris from the field and sending away the wounded as fast as their condition would permit. Colonel Alleman, in his official report, gives the following schedule of property as having been collected from the battle-field: “Twenty-six thousand six hundred and sixty-four muskets, nine thousand two hundred and fifty bayonets, one thousand five hundred cartridge boxes, two hundred and four sabres, fourteen thousand rounds of small-arm ammunition, twenty-six artillery wheels, seven hundred and two blankets, forty wagon loads of clothing, sixty saddles, sixty bridles, five wagons, five hundred and ten horses and mules, and six wagon loads of knapsacks and haversacks.” The ordinance stores he shipped to the Washington Arsenal, and the remainder of the government property he turned over to an agent of the War Department. From the various camps and hospitals on the battle-field, and in the surrounding country, he reports having collected and sent away to northern cities, “twelve thousand and sixty-one wounded Union soldiers, six thousand one hundred and ninety-seven wounded rebels, three thousand and six rebel prisoners and one thousand six hundred and thirty-seven stragglers….”

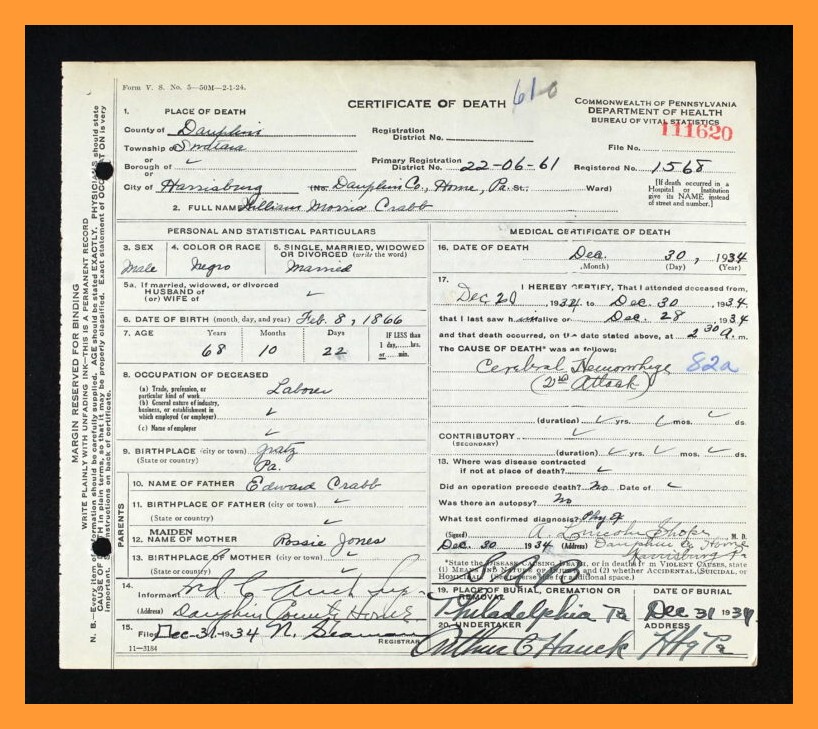

Following the Civil War, Edward Crabb returned to Gratz where he married Catherine “Rossie” Jones and began raising a family. Rossie was a descendant of another of the many African American families of the Lykens Valley area. Their first son, William Morris Crabb, was born in Gratz on 8 December 1866. His death certificate, 30 December 1934, shown below, confirms his birthplace as Gratz, his race as Negro, and the names of his parents as Edward Crabb and Rossie Jones.

In the Census of 1870, the family appears in Gratz. Edward is a shoemaker and his race is mulatto.

In the Census of 1880, the family is in Hubley Township, Schuylkill County, where Edward was then working as a coal miner. His race was given as Black. It is not known at this time when the Edward Crabb family moved from Gratz to Hubley Township or why they moved. In the post-Civil War years attitudes of the dominant population of Whites toward Blacks began to change in the Lykens Valley area and gradually, those Black families who had pioneered in the region, began to disappear, or if they were able to pass, some chose to remain. Thus today, there are descendants of the pioneer Peter Crabb still living in the Lykens Valley, but all as White. The erroneous view that African Americans never lived in Gratz could not have developed until after the last African Americans lived there – perhaps some time just after Edward Crabb moved to Hubley Township in the 1870s.

Following his death on 26 October 1886 in Hubley Township, Edward Crabb was buried in Gratz Union Cemetery (also known as Simeon’s Cemetery). Two of his children are also buried in the same plot. There is no evidence to suggest that he was ever recognized at his grave site as a Civil War veteran – by the G.A.R. (which in Gratz did not permit Blacks as members), by the American Legion, or by the current V.F.W. More research must be done to determine when this racial discrimination first occurred and who was involved in promoting it.

So, the question now is, “Why isn’t Edward Crabb recognized as a Civil War soldier?” He is recognized by the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania as such. He also is recognized as such in the “official” history of Gratz, page 341, which was published in 1997. However, that Gratz history does not mention any race or national origin for the the Crabb family.

It can now be stated unequivocally that Edward Crabb is not recognized because he was an African American. There has been a deliberate effort on the part of the Gratz Historical Society to hide and erase the fact that some of the earliest settlers of Gratz were African Americans and their sons and grandsons served honorably in the Civil War.

_________________________________

The update will be presented tomorrow.

This post was first published,in part, on The Civil War Blog on 1 July 2016.

Corrections and additional information should be added as comments to this post.

Posts such as this grieve me, yet the truth must be told, and I appreciate your willingness to do so and all the time and effort you put into researching this information.

Can a fund be established to repair/replace the gravestones for these individuals?

I am related to the Crabbs, and am annoyed by this attempt to make this into a racial incident, where non probably exists. Most people know that the Crabb family was partly colored, or, in more comtemporary terms, black. It was a secret to nobody. Why has this person chosen to try to inflame everyone, and make the whole community appear racist, when that’s probably not even so? Was this person so desperate to find racism that he had to invent it?