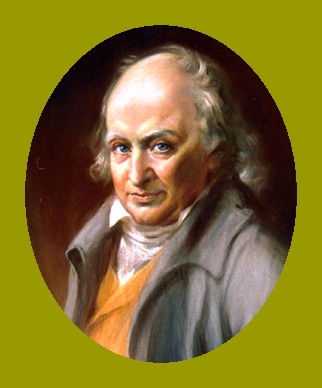

A portrait of Michael Gratz (1740-1811) of Philadelphia, the father of Simon Gratz (1773-1839), the founder of Gratz, Dauphin County, Pennsylvania.

The following story was taken from B. & M. Gratz Merchants in Philadelphia, 1754-1798. It is available as a free download from Google.

The father and grandfather of Simon Gratz were both well established in business by the outbreak of the Revolutionary War. In fact, they had been very active in supplying needs to troops during the French and Indian War. Both men had become well acquainted with individuals who had high positions in the Continental Government as well as the Continental Army. That advantage may have given them special advantages in trade during the Revolutionary War.

Simon’s father, Michael Gratz, was a merchant in Philadelphia, and had a fleet of ocean-going ships. His grandfather, Joseph Simon had been settled in Lancaster. He had a few enterprises going – trading with the Indians (furs and other items), a shop in Lancaster, and he acted as a middle man selling and trading goods to other merchants. Both had many other interests.

There are a number of accounts which give first-hand information concerning the type of goods these two men supplied and there were some interesting circumstances surrounding their business deals.

In September 1776, Col. Mackay contacted the Gratz brothers for a quantity of blankets and leggins-stuff He wanted to buy them to be distributed to the companies of soldiers. Of the price he “expected it to be as reasonable as possible.”

A friend of the family wrote from Swedes Ford in December 1777 requesting some fine blue cloth… “enough as will make a coat, and as much buff or white as will make a tucket and breeches, with the trimmings…” he was in need of a new Continental uniform for the holidays. “If you can get it and send me the bill, I will return you the money is I can raise so much. If not, you can wait will my father returns, as he is my banker.

Because of their close association with the officers of the Continental Army, news of the war reached the Gratz family quickly. Business correspondence usually included news of many of the battles – some meager details, other more in depth. Two letters received by Michael Gratz in September 1776 described how the Battle of Long Island began. The first was written by Alexander Abrahams on September 2:

“Our people are obliged to evacuate Long Island with considerable loss on both sides. Generals Sullivan and Sterling are taken prisoners. The number of slain is unknown.”

The next day, September 3, Nathan Bush gave this account:

“Thursday evening late, the Regulars landed on Long Island, 10,000 men within tow miles of our line. About midnight our advanced guard noticed two men in a watermelon patch, which they fired on, when a number of the men who lay concealed returned the fire. This brought on a general fire from our line. The enemy retreated and our people pursued with three battalions under the command of Colonel Miles, Atlee and Smallwood of the Maryland forces. The Regulars continued their retreat near half-a-mile and our people pursued until they got to where the field pieces were, when they rallied and having a re-enforcement and artillery and a number of light horse, they made a great havoc among our men. After taking General Sterling and Col’s Miles and Atlee prisoners, they put our men to flight and many of the men and officers were killed. I am told the loss on our side is between eight and nine hundred, but the loss on their side is much greater.

“The next night being foggy, our people retreated from Long Island with all their cannon excepting two large ones which they left spiked up, and in the morning, the Regulars took possession of them. I am just now told that they have landed a number of men at Harley. If so, I imagine they’ll soon be in possession of New York. He hear say, that if the General is forced to leave New York, he has orders to set fire to it.”

Note: Capt. Albright Deibler, and his company of men from our area fought, and many died or were taken prisoner in that battle. Capt. Deibler himself was lost and Capt. Hoffman took his place.

The Gratz brothers had problems in their foreign trade. There was always a danger that their ships would be seized while crossing the ocean. At least one was “taken by the enemy.” Another incident involved a ship partly owned by Michael Gratz. This time, the Phenix, with Capt. Cunningham, began a privateering cruise, having orders to capture any Portuguese ships which showed hostility. Portugal was expected to take sides with England. Accordingly, Capt. Cuningham returned to port with the Portuguese ship, Our Lady of Carmel. A suit followed, and in the end, Congress wishing to appease the Portuguese government forced the ship owners to pay for the value of the ship and its contents.

When Philadelphia was seized by the British, many of the residents left. Most of the Jewish families fled to Lancaster. It is not surprising that Michael Gratz had his family removed to that place, since her parents were still living there. They left Philadelphia before June 1777, and did not come back until late July 1778.

Joseph Simon had a large general store in Lancaster. He also had a friend who made guns, and in fact they were partners in business for a few years. They sold guns, gunpowder, blankets, clothing, and drums to the Continental Congress for the use of the army.

In a letter to Major Ephraim Blaine who was in Carlisle in June 1776, Joseph Simon‘s clerk and partner apologized because there is a short supply of blankets and shoes:

“If I had known that the country-made blankets, which are thin and light, would have done, I might have got a few; others not to be had. As I told you when you were here, a collection had been made in this town [Lancaster] for blankets for the Continental troops. I cannot get any quantity of good shoes, and those the tanners have are very ordinary.”

Another letter written in April 1777 to a Colonel who wanted to supply two companies of men with rifles, speaks of 120 new rifles that Mr. Simon wanted to sell for a bit more than six pounds each.

Joseph Simon played another role during the war. in 1778, he contracted with the Board of the War of the Continental Congress to supply British prisoners with their every day needs. Those needs were: wood, straw, tobacco, soap, candles, etc., along with clothing and food. There were five different prison camps: Lancaster, Easton, Fredericktown, Winchester, and Fort Frederick. Mr. Simon sometimes experienced delays in receiving compensation for the supplies, and at least one time, he “took the liberty to trouble his Excellency, General Washington” about the problem.

______________________________________

Corrections and additional information should be added as comments to this post.