A portrait of Levi Coffin (1798-1877) – “President” of the Underground Railroad.

The Underground Railroad was the name given to a 19th century hidden network of routes by which African-Americans escaped from slavery to freedom – for the most part, to the north and to Canada. Abolitionists aided the escaping African-Americans and established a series of safe-houses or hiding places along the way as well aiding the escapees to move from one stop to another – either under the cover of darkness, or hidden among cargo moving north, or in broad daylight disguised as travelers who normally would not be stopped. The term “railroad” was used to describe the operation of moving “passengers” from “station” to “station” (or “depot” to “depot”). The abolitionists who assisted were called “conductors.” The “stationmasters” were those who assisted by providing hiding places in their homes or barns. The state coordinators were referred to as “superintendents” and the overall national head was referred to as the “president.” Many historians agree that the “president” of this operation was Levi Coffin (1798-1877) a Quaker abolitionist who was born in the south, but made his home in Indiana and Ohio while the Underground Railroad was at its peak.

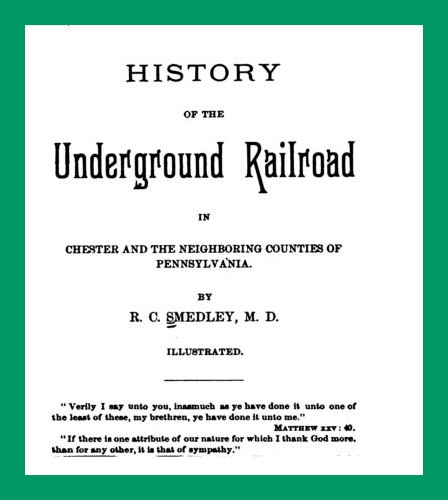

The name “Underground Railroad” was believed to have been first used in Columbia, Pennsylvania. In his book The History of the Underground Railroad in Chester and the Neighboring Counties (1883), R.C. Smedley states the following:

In the early part of concerted management slaves were hunted and tracked as far as Columbia [Pennsylvania]. There the pursuers lost all traces of them. The most scrutinizing inquiries, the most vigorous search, failed to educe any knowledge of them. Their pursuers seemed to have reached an abyss, beyond which they could not see, the depths of which they could not fathom, and in their bewilderment and discomforture they declared there must be an underground railroad somewhere. This gave origin to the term by which this secret passage from bondage to freedom was designated thereafter.

The Smedley book is a free download from Google Books.

Of course, other sources differ on the term’s origin – some claiming the origin occurred in the Kentucky-Ohio area and others giving the credit to Levi Coffin himself. Nevertheless, Columbia’s claim to be the place where the term originated is enhanced by the history of the town as a major stopping place for freedom-seekers on their way north. Columbia is also important to the residents of the Lykens Valley area as it is a town on the Susquhanna River south of Harrisburg and was the object of a Civil War incident, the burning of the Wrightsville-Columbia Bridge, which took place in June 1863, days before the Battle of Gettysburg. Credited with saving the town of Wrightsville after the bridge was set on fire, was Confederate General John Brown Gordon (see post entitled Naked Man Visits Rebs on Rabidan). Many believe if the bridge had not burned, the Confederate objective would have been the town of Columbia along the Susquehanna’s eastern bank, and with nothing to stop the rebel advance between Columbia and Harrisburg, the course of the war would have changed to a Union disaster.

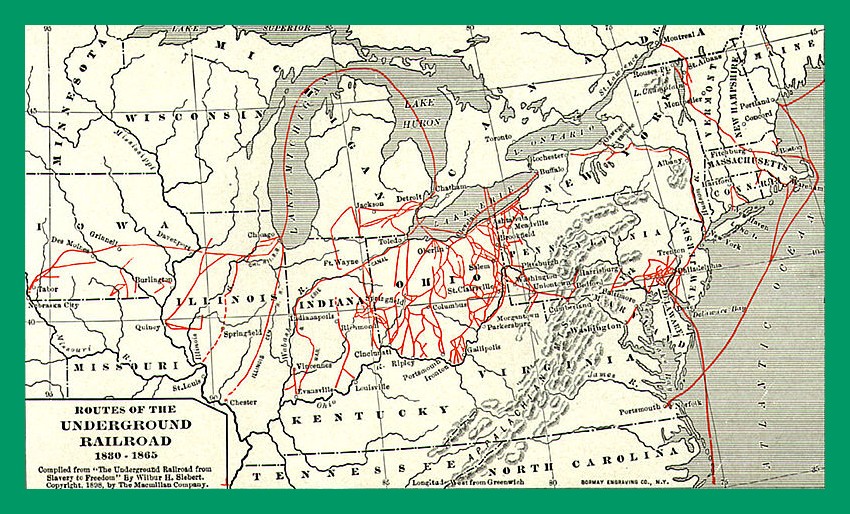

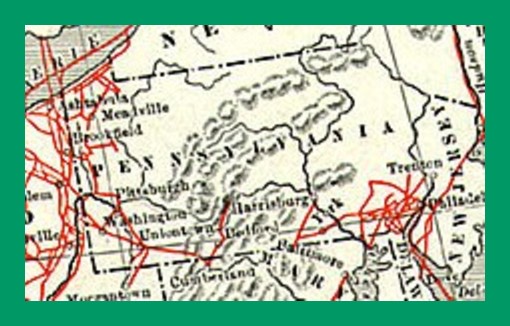

The above map shows some of the major routes that escapees used to go north. But the map only tells part of the story as far as Pennsylvania is concerned. The “cut” of the map shown below gives Harrisburg as a destination but does not show where the “railroad” continued north from Harrisburg.

To the right of the “g” in Harrisburg is a vertical line representing the Susquehanna River. And, to the right of the Susquehanna River and slightly above the “g” in Harrisburg is a peanut-shaped mountain which is presumably Peter’s Mountain, the dividing line between upper and lower Dauphin County. The presumption from this map is that the Underground Railroad ended in Harrisburg. The red lines on the map that appear to go north and into New York or Canada are in western Pennsylvania. Another concentration of lines appears in southeastern Pennsylvania around the city of Philadelphia with an escape route through New Jersey, near New York City, and into New York State. This map provides no clues to the role of central Pennsylvania in the Underground Railroad – or the role of Harrisburg, other than a final destination.

No one knows for sure how many African-Americans escaped to freedom via the Underground Railroad. Some Civil War estimates give numbers in the hundreds of thousands. Canadian records could give some clue, but only by breaking down the total number of blacks into categories of native-born Canadians vs. those who emigrated there can some sense be made of the figures. No one has yet done this with any degree of certainty. Thus we are left with speculation.

In addition to those who fled into Canada, many settled in welcoming communities along the way in the United States – Harrisburg included. The Crabb family that arrived in Gratz in the early part of the 19th century is still of unknown origin. Perhaps they were escapees from slavery and found in Gratz a welcoming community where they could practice their trade of blacksmith. Sons of this early Lykens Valley area settler, Peter Crabb (1787-?) were born in Gratz and fought in the Civil War.

Adding to the difficulties of the escapees were the notorious slave-catchers who were operating in both south and north under the auspices of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850. Many escapees never made it to freedom. Some were killed or died along the way. Others were captured and were returned to slavery.

In Part 2, the role of Harrisburg in the Underground Railroad will be discussed.

___________________________________

The portrait of Levi Coffin is from Wikipedia and is in the public domain because its copyright has expired. The map of the Underground Railroad routes is also from Wikipedia.

Previously posted on The Civil War Blog on April 10, 2011.

Corrections and additional information should be added as comments to this post.

[African American]