A brief “official” history of Tower City and Porter Township , Schuylkill County, Pennsylvania, was produced for the centennial celebration in 1968. Included was a section on the history of bootleg coal mining.

___________________________________

COAL BOOTLEGGING BECAME ILLEGAL BUSINESS

About 1923, an economic collapse was evident in the anthracite region.

During World War I, the United States Government, in order to avoid a disastrous strike, nationalized the railroads and restricted the transportation of domestic cola to the metropolitan areas. Many home owners were without fuel over the winter months and converted to oil and gas. The lengthy 1922 anthracite strike extended over the winter and again the coal supply was restricted and more conversion to other fuels resulted.

Mine owners failed to develop automatic heaters and stokers although they were then extensively used by the oil and gas industry. Coal prices continued to advance to such a point that oil and gas were in a favorable position with the former “king” of fuels.

The operator then resulted to the open pit or strip mining method to cheapen the price but this resulted in the abandonment of many deep mine operations, throwing thousands of men out of work.

in southern Schuylkill County, there was only one large land owner and producer in 1927 – the Philadelphia and Reading Coal and Iron Company which then had ten mines in full production yet two years later only four were in operation. Good Spring Colliery, with a daily production of 2,000 tons, was closed in 1929, idling 900 men. The same year, Lincoln Colliery, with an 1800 daily ton capacity, was also abandoned, leaving 800 more idle. Only East Brookside and West Brookside survived, although production and manpower were gradually reduced. Coal production ceased at East Brookside in 1936 but the water shaft continued to operate to prevent the flooding of the West Brookside workings. In that year West Brookside had only 500 men employed and that workforce was gradually reduced until 1938, when it too was abandoned.

The resulting unemployment was a terrific blow to the community. Good Spring, Lincoln, and the two Brooksides at full capacity employed almost 3,000 men. Finding employment for so great a number seemed impossible, especially during the world-wide great depression then at its height.

The destitute circumstances called for desperate measures, and they were not long in coming. The only work these men had ever known was mining, and in the thousands of acres of mountain land lay millions of tons of the finest domestic fuel in the world, the veins outcropping within a few feet of the surface. It seemed only natural to them to avail themselves of this buried treasure, so they helped themselves.

Initially, they dug coal to supply their own fuel needs, but soon it became a business and the illegally mined product was sold locally and transported by truck to surrounding areas.

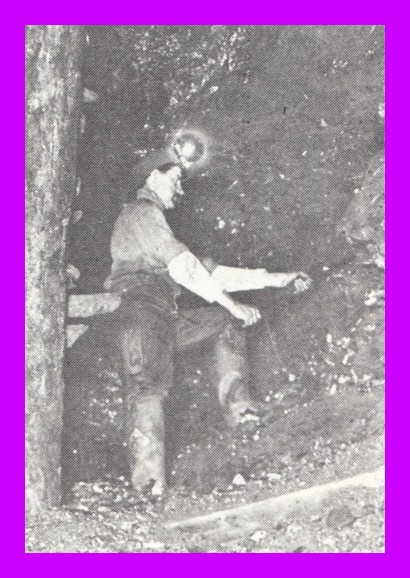

The first operations was crude, employing the same hand methods used 100 years before when coal was mined. A shaft was sunk to the vein outcropping, shored with timber cut from the operator’s lands, the coal brought to the surface by a hand-operated windlass, cracked by a hammer, run over a crude screen, placed in bags, and carried away in the dark of night.

A FLEA BITE

At the outset coal operators did little to stop this practice, for, as one operator said, “It is but a flea bite so far as total production is concerned.” But the flea bite grew to be a festering boil and in 1934 bootleg mining was an established industry with an estimated total production in the anthracite area of two and one half million tons. Ten thousand tons were shipped to Philadelphia weekly with thousands more to Baltimore and New Jersey points. By 1935, about 20,000 people were dependent upon this illegitimate trade for a living — mining, cleaning, preparing and trucking the material to market.

The mine at last realized that they were faced not only with serious competition from oil and gas, but by the cheaper anthracite taken from their own lands. The coal company police forces were augmented and patrolled the mountains to ferret out the bootleg operations, with orders to arrest all miners as trespassers. This did not prove successful as the magistrates and courts were sympathetic to the men eking out a precarious living to feed themselves and their families, and most of those prosecuted were freed on legal technicalities.

The operators then issued orders to close all illicit workings by explosives, but by then the miners were fairly well organized and developed a system of alerting all miners of the presence of the company police and the direction in which they were proceeding. All in the vicinity hastened to the danger spot when the signal was given, gathered around the workings and prevented any danger thereto.

In 1939, the Philadelphia and Reading Coal and Iron Company, under bankruptcy proceedings, obtained permission from the Federal District Court to dispose of all its unproductive land, reserving to itself all coal banks and land where coal could be mined by the cheap strip-mine method. Since most of the company’s land was concentrated in the west end of Schuylkill County, our community was most seriously affected by this transfer. Thousands of dollars in taxes on which the boroughs, townships and school districts depended were unpaid and chaos ensued.

Teachers and municipal employees were unpaid for months at a time and municipalities and school districts were virtually bankrupt. The ire of all citizens was justifiably aroused and all hope the landowners ever had of wiping out the so-called bootleg industry was now abandoned.

So bitter had feelings become that on July 10, 1941, when the landowners attempted to remove a stripping shovel into an area east of Good Spring, a crowd of 1800 independents was rapidly assembled and prevented the movement of the equipment. The coal police were unable to cope with the situation and the sheriff was called, who in turn appealed to the State Police for help. But still the men refused to disperse and bloodshed followed. Thirteen miners were wounded by gunfire and twenty others were injured in the numerous skirmishes which occurred. Both sides eventually withdrew from the battlefield but the event proved to be a unifying force to the independent miners.

In 1940, a movement to organize the men was begun under the leadership of Clyde L. Machamer of Reinerton, and within two years it had a membership of 2500. A non-profit corporate charter was secured from the local courts under the name of Miners, Breakermen and Truckers Association but in 1957, the name was changed to Independent Miners and Associated.

In 1942, the membership had increased to 4,000 and in West Schuylkill County and excess of four and one half million tons was produced and processed. This association was instrumental in securing leases from the owners for its members on a royalty basis and effectively insisting that taxes be paid from the royalties.

COAL SLIDES AGAIN

By 1967, the membership had fallen to 2,000, and production to one and three-quarter tons. This was due to the tremendous demand for anthracite as a fuel for energy production. Coal production in the entire anthracite dropped from a high of almost 100,000,000 tons during World War I to 12,000,000 tons in 1967, and of the latter total, almost one-third was produced by independents and 65 percent of all deep-mined coal was produced by independents and most of that in the West End. During the peak years of independent mining there were 112 operators in Porter Township employing 1800 men with at least 800 more indirectly benefited by employment in the breakers and as truckers. Today [1968] there are only 12 active mines employing but 250 men.

_______________________________________

Text above is from the West Schuylkill Herald (Tower City), June 26, 1968, via Newspapers.com, and was also printed in the souvenir book for the Tower-Porter Centennial in 1968.

Corrections and additional information should be added as comments to this post.