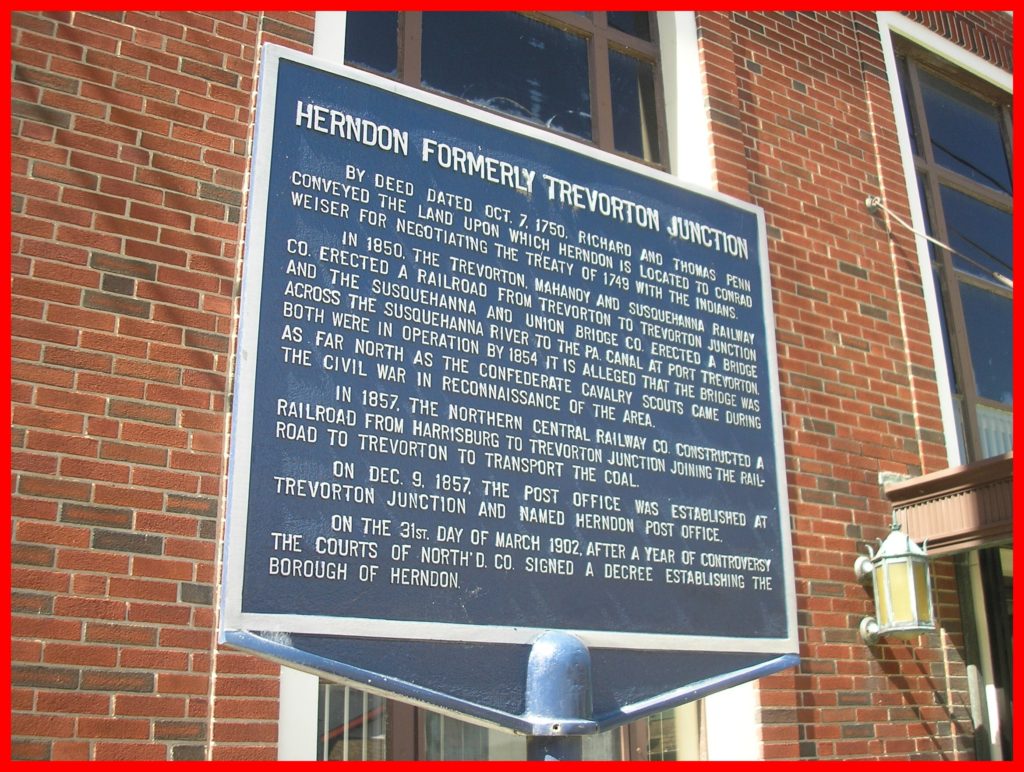

At the side of the old Herndon National Bank building in Herndon, Northumberland County, Pennsylvania, is an historical marker. The text of the marker reads:

Herndon Formerly Trevorton Junction

By deed dated October 7, 1750, Richard Penn and Thomas Penn conveyed the land upon which Herndon is located to Conrad Weiser for negotiating the Treaty of 1749 with the Indians.

In 1850, the Trevorton, Mahanoy and Susquehanna Railway Company erected a railroad from Trevorton to Trevorton Junction and Susquehanna and Union Bridge Co. erected a bridge across the Susquehanna River to the Pennsylvania canal at Port Trevorton. Both were in operation by 1854. It is alleged that the bridge was as far north as the Confederate cavalry scouts came during the Civil War in reconnaissance of the area.

In 1857, the Northern Central Railway Company constructed a railroad from Harrisburg to Trevorton Junction joining the railroad to Trevorton to transport the coal.

On 9 December 1857, the post office was established at Trevorton Junction and named Herndon post office.

On the 31 March 1902, after a year of controversy the courts of Northumberland County signed a decree establishing the Borough of Herndon.

This marker contains a statement that needs further exploration – that Confederate scouts conducted reconnaissance as far north as Trevorton Junction or Herndon.

In June 1863, as the Confederate army moved into Pennsylvania, the Northern Central Railroad moved its locomotives and cars north to Sunbury to avoid them being captured or destroyed by the enemy – or trapped on rails between burned bridges. The Sunbury Gazette of June 20, 1863 reported:

The railroads and sidings about our town are filled with the cars and locomotives of the Northern Central Railroad. They were brought here to keep them out of the hands of the rebels, the lower part of the road being in danger of a raid by them.

The Harrisburg Weekly Patriot and Union on June 25, 1863 presented the following blurb as part of an article on the advance of the rebels toward Gettysburg:

Gen. Jenkins, with a force of mounted infantry 1100 strong, is said to be moving towards Gettysburg, and doing much mischief. He is said to have designs on the Northern Central Railroad.

But the Philadelphia Inquirer, on June 29, 1863, noted that the rolling stock at the southern end of the Northern Central Railroad was being moved to Baltimore:

BALTIMORE, June 28th – Midnight – All the rolling stock… has been brought to Baltimore for safety, as has also much of the Northern Central.

The Philadelphia Inquirer of June 29, 1863 presented the following report:

HARRISBURG, June 27, 10 P.M. [Special to the New York Herald]….

It is reported that the Northern Central Railroad has been destroyed at York Haven….

All the citizens of Harrisburg are armed and will cross the river tomorrow.

The Rebel cavalry scouts are seven miles this side of Carlisle, and a battle is expected here on Sunday….

About six hundred Rebel cavalry are in Carlisle….

York has been occupied, and a portion of the bridges on the Northern Central Railroad, this side of that place have been burned.

Then on July 5, 1863, the Sunbury American reported:

The engines of the Northern Central Railroad are nearly all at this place, and have been kept fired up day and night. Among them are eleven of Baldwin’s ten wheeled engines. A few nights since, some twenty-five engines were blowing off steam simultaneously. The screeching roar of escaping steam was awful to delicate nerves.

Nowhere in any of these reports was it noted that Confederate cavalry or scouts had gone as far north as Trevorton Junction or Herndon.

From the Proceedings of the Northumberland County Historical Society, Vol. VIII, p. 173, comes the following story:

In June 1863, eight men on horseback came across the Herndon bridge, rode about on the eastern side of the Susquehanna and after a short stay rode back and sent down the western side of the river. The local telegraph operator, who was the uncle of the late John D. Bogar, of Herndon telegraphed his suspicion to authorities at Harrisburg stating that he thought the men were rebels. It subsequently turned out that the men were General Early and his staff, reconnoitering for Lee’s army prior to the Battle of Gettysburg.

This was the high-water mark of the Rebellion. No known rebel enemy came further north than the town of Herndon.

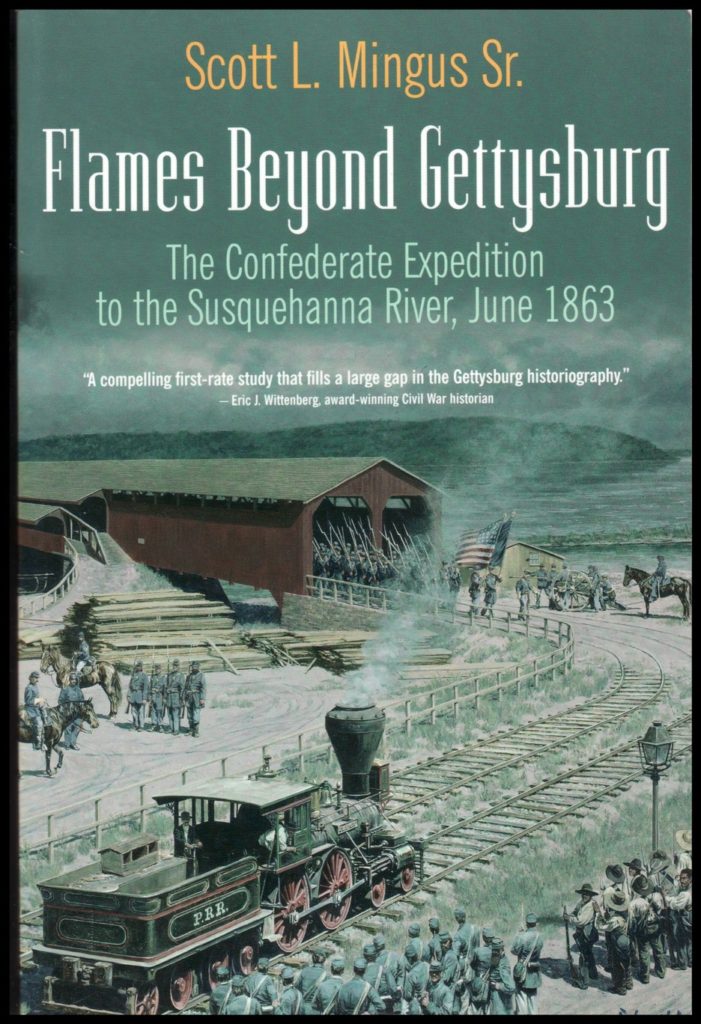

Did Gen. Jubal Early cross the Susquehanna Bridge into Trevorton Junction? To determine if Early had an opportunity to go that far north, an e-mail was sent to Scott L. Mingus Sr., author of Flames Beyond Gettysburg. Mingus has written the definitive work on the activities of the Confederate army along the Susquehanna River in the days preceding the Battle of Gettysburg.

On April 29, 2011, Mingus responded:

Early’s personal movements are very well known after he entered Pennsylvania, and they form the backbone of my book, Flames Beyond Gettysburg.

Early and his division arrived in Pennsylvania on June 23 and marched north in the Cumberland Valley to Greenwood, where they camped for 2 days.

Early then followed today’s US 30 from the Chambersburg region across South Mountain into Gettysburg on June 26, and then on to York on the 27th. He rode to Wrightsville the night of June 28, and stayed in York on the 29th. The 30th he and his men headed west to Heidlersburg and then south to Gettysburg on July 1, arriving about 2 p.m. during the first day of the battle.

He nor any of his staff ever went to Herndon.

Gen. Jubal A. Early (1816-1894) – Definitely not in Herndon!

If not Early, then who crossed the bridge? Was it Gen. J. E. B. Stuart? Mingus continues:

No, it wasn’t Stuart. The scouts would have been from Albert G. Jenkins‘ Brigade of Ewell’s Corps. Jenkins’ men are known to have roamed through the area in late June scouting the region. They fought two small battles near Mechanicsburg and Camp Hill.

Who was Albert G. Jenkins? From Wikipedia:

Jenkins was born to wealthy plantation owner Capt. William Jenkins and his wife Jeanette Grigsby McNutt in Cabell County, Virginia, now West Virginia. At the age of fifteen, he attended Marshall Academy. He graduated from Jefferson College in Canonsburg, Pennsylvania [about 30 miles south of Pittsburgh], in 1848 and from Harvard Law School in 1850. Jenkins was admitted to the bar that same year and established a practice in Charleston, before inheriting a portion of his father’s sprawling plantation in 1859. He was named a delegate to the Democratic National Convention in Cincinnati in 1856, and was elected as a Democrat to the Thirty-fifth and Thirty-sixth United States Congresses….

During the Gettysburg Campaign, Jenkins’ brigade formed the cavalry screen for Richard S. Ewell‘s Second Corps. Jenkins led his men through the Cumberland Valley into Pennsylvania and seized Chambersburg, burning down nearby railroad structures and bridges. He accompanied Ewell’s column to Carlisle, briefly skirmishing with Union militia at the Battle of Sporting Hill near Harrisburg. During the subsequent Battle of Gettysburg, Jenkins was wounded on July 2 and missed the rest of the fighting. He did not recover sufficiently to rejoin his command until autumn.

According to Wikipedia‘s history of Mechanicsburg:

On June 28, 1863, Confederate troops led by Brig. Gen. Albert G. Jenkins raided Mechanicsburg, and two days later, met with Union forces in the Skirmish of Sporting Hill, just east of town. It is known as the northern most engagement of the Civil War. Following the Skirmish of Sporting Hill, the Confederate forces retreated south into the little town of Gettysburg where the Battle of Gettysburg would be fought.

Further information on Jenkins can be found in John A. Miller’s A Short History of Jenkins’ Brigade During the Pennsylvania Campaign:

On June 28th, General Jenkins marched into the town of Mechanicsburg. After skirmishing with Federal Cavalry, Jenkins’ Brigade occupied Mechanicsburg. General Jenkins divided his brigade into two columns. He sent Colonel Milton Ferguson with the 16th Virginia, the 36th Virginia and Jackson’s Artillery along the Carlisle Pike. The rest of the Brigade moved along Trindle Spring Road and advanced toward the Susquehanna River, about four miles from Harrisburg, Pennsylvania….

On June 29th, a portion of Jenkins’ Brigade engaged the Federal troops from Oyster Point. General Jenkins ordered a concentration of rifle and artillery fire to cover his reconnaissance of the Union defenses of Harrisburg. The entrenchment consisted of Fort Washington and Fort Couch that were located on Hummel Heights. While General Jenkins’ men were engaged at Oyster Point, General Richard S. Ewell ordered General Rodes to move his infantry east for an attack on Harrisburg….

It seems that Jenkins’ movements can also be accounted for during this period. However, one clue in the above quotes may indicate that the incident actually did take place. Jenkins was known for dividing his brigade and it is entirely possible that some of his men did ride up the western side of the Susquehanna on Jenkins’ orders and cross the bridge into Herndon. However, no contemporary accounts have been found of the incident and the allegation is based on an oral history that has yet to be confirmed with fact.

One final story needs to be noted. This is from an article that appeared in the Selinsgrove Times on 29 November 1940, entitled “The Heroine of Herndon” and is from the “Legends of Col. Henry W. Shoemaker.”

One of Adam Leader’s stories tells how a Confederate patrol, by a daring stroke, had crossed the river bridge on the ties, determined to wreck and burn railroad intersections at Sunbury. The slight nickering of their horses caused the hired girl of the old posting inn in her tiny room under the roof, to peer out, hearing them say, “We dare not ask anybody the way, but if we can make out the weather vane, we known that Sunbury lies to the North.

Quick as a flash the dark-eyed girl reached for the pivot, just above her bed on which was embossed the direction of the compass, and she pointed the north arrow east, up Schmalz Hill and into the wilds of the Fishback regions and Klingerstown Gap.

Not a moment too soon, as they struck their flint and steel and saw the vane on the cupola of the hotel, the arrow which surmounts that curious sign preserved to this day – ‘Herndon Ho’ – then a gold horseshoe, then SE.’ It was a lucky horseshoe for Sunbury and the Northern cause, as putting spurs to their horses, they rode up the steep street in a cloud of dust, past the present post office and what is now J. Paul Garrett’s general store, Leader’s old livery and Editor Zeigler’s office. And what became of them and where they got to, no one can tell, but the dark-eyed girl had saved Sunbury.

We may never know for certain whether Confederate scouts entered Herndon in June 1863. The historical marker correctly uses the word “alleged” when telling of the incident. If anything, it makes a good story and certainly is part of the lore and legend of the area within the greater Lykens Valley area. Anyone knowing anything further about this alleged incident is urged to contribute it.

____________________________________________

Some of the information for this post was taken from Wikipedia, including the portrait of Jubal Early. The news “clippings” are from the on-line resources of the Free Library of Philadelphia. The stories from the Northumberland County Historical Society Proceedings, the Selinsgrove Times, and the Sunbury newspapers were reported in The Trevorton, Mahanoy and Susquehanna Railroad, available from Sunbury Press; they were also told in the centennial book, The Borough of Herndon Pennsylvania, 1902-2002, Memories Last a Lifetime. Permission to quote the e-mails was obtained from Scott L. Mingus Sr. His book, Flames Beyond Gettysburg is available from Savas Beatie.

This post was first published on the Civil War Blog, May 20, 2011.

Corrections and additional information should be added as comments to this post.