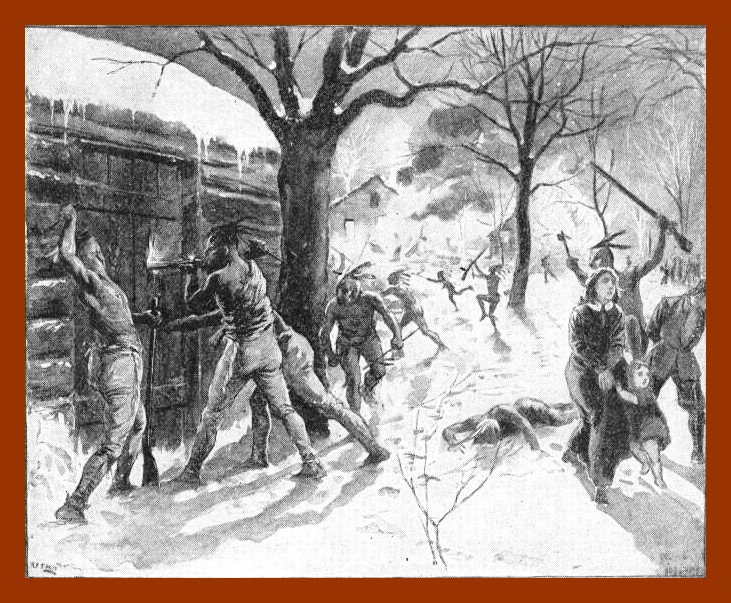

A graphic image made in 1900 by William Henry Lippincott of an Indian raid on a colonial settlement at Deerfield, Massachusetts. While the artist attempted to depict an event that occurred over a half century before the French and Indian War, so-called first-hand accounts of incidents that occurred in the area presently known as Dauphin County were remarkably similar.

The text below is from George H. Morgan‘s Centennial of the Settlement, Formation and Progress of Dauphin County, Pennsylvania, from 1785 to 1876, published in 1877 by the Telegraph Steam Book and Job Printing House. The book is available as a free download from the Internet Archive.

The chapter on “The French and Indian War” is presented in this post. In the chapter the author focuses on Indian raids, the Paxton Boys and the Conestoga Massacre, the conflict between the pacifist Quakers and Moravians and the frontier settlers’ perceived need for defense, the development of the forts along the Susquehanna River (including Fort Halifax), and other aspects aspects of the war that specifically related to Dauphin County. The chapter is filled with transcripts of letters and other documents.

_______________________________________________

THE FRENCH AND INDIAN WAR

With the exception of occasional personal or individual disputes, a friendly feeling had existed between the Indians and the inhabitants of Pennsylvania for a period of nearly seventy years. In 1753, however, a different spirit manifested itself in the conduct of some of the Indians in the western part of the colony. They united themselves with the French against the English, many of whom, at the instigation of their new allies, they murdered most cruelly. The inhabitants of the frontiers were in a panic, for the Indians, true to their character, when enemies, struck wherever an opportunity presented itself, sparing neither sex nor age.

The settlers in the region comprising this county, partook in the prevailing alarm, and sent the following petition to Governor Hamilton:

The humble petition of the inhabitants of the townships of Paxton, Derry and Hanover, Lancaster County [now Dauphin County], humbly sheweth, that your petitioners being settled on and near the river Susquehanna, apprehend themselves in great danger from the French and French Indians, as it is in their power several times in the year to transport themselves, with ammunition, artillery and every necessary, down the said river — and their conduct of late to the neighboring provinces, increases our dread of a speedy visit from them, as we are as near and convenient as the provinces already attacked, and are less capable of defending ourselves, as we are unprovided with arms and amunition [sic], and unable to purchase them. A great number are warm and active in these parts for the defence of themselves and country, were they enabled so to do, (although not such a number as would be able to withstand the enemy). We, your petitioners, therefore humbly pray, that your Honor would take our distressed condition into consideration, and make such provision for us as may prevent ourselves and families from being destroyed and ruined by such a cruel enemy; and your petitioners, as in duty bound, will ever pray.

Dated, July 22, 1754.

Thomas Forster, James Armstrong, John Harris, Thomas Simpson, Samuel Simpson, John Carson, David Shields, William McMullen, John Colt, William Armstrong, James Armstrong, William Bell, John Daugherty, James Atkins, Andrew Cochran, James Reed, Thomas Rutherford, T. McCarter, William Steel, Samuel Hunter, Thomas Mays, James Coler, Henry Renicks, Richard McClure, Thomas Dugan, John Johnson, Peter Fleming, Thomas Sturgeon, Matthew Taylor, Jeremiah Sturgeon, Thomas King, Robert Smith, Adam Reed, John Crawford, Thomas Crawford, John McClure, Thomas Hume, Thomas Steene, John Hume, John Craig, Thomas McClure, William McClure, John Rodgers, James Peterson, John Young, Ez Sankey, John Forster, Mitchell Graham, James Toalen, James Galbraith, James Campel, Robert Boyd, James Chambers, Robert Armstrong, John Campbell, Hugh Black, Thomas Black.

________________________________________

The petition was read in Council August 6, 1754.

Shortly after the defeat of Gen. Braddock, July 9, 1755, the French and their Indian allies, encouraged by their success, pushed their incursions into York, Cumberland, the northern part of Lancaster (now dauphin), Berks and Northampton counties, and the massacres which followed were horrible beyond description. King Shinges, as he was called, and Captain Jacobs were supposed to have been the principal instigators of them, and a reward of seven hundred dollars was offered for their heads. It was at this period, that the dead bodies of some of the murdered and mangled were sent from the frontiers to Philadelphia, and hauled about the streets, to inflame the people against the Indians, and also against the Quakers, wo whose mild forbearance was attributed a laxity in sending out troops. The mob surrounded the House of Assembly, having placed the dead bodies at its entrance, and demanded immediate succor. At this time the above reward was offered.

The condition of affairs in the interior and western part of the Province are thus described by Gov. Robert Morris in his message of July 24, 1755, to the Assembly, in relation to Braddock’s defeat:

This unfortunate and unexpected change in our affairs deeply affects every one of his majesty’s colonies, but none of them in so sensible a manner as this province; while having no militia, is thereby left exposed to the cruel incursion of the French and barbarous Indians, who delight in shedding human blood, and who make no distinction as to age or sex — as to those that are armed against them, or such as they can surprise in their peaceful habitations –all are alike the objects of their cruelty — slaughtering the tender infant, and frightened mother, with equal joy and fierceness. To such enemies, spurred by the native cruelty of their tempers, encouraged by their late success, and having now no army to fear, are the inhabitants of this province exposed; and by such must we now expect to be overrun, if we do not immediately prepare for our own defence; nor ought we to content ourselves with this, but resolve to drive to, and confine the French to their own just limits.

On the 23d of October, 1755, forty-six of the inhabitants about Harris’ Ferry (now Harrisburg) went to Shamokin, to enquire of the Indians where who they were, who had so cruelly fallen upon and ruined the settlement on Mahahony Creek. On their return from Shamokin, they were fired upon by some Indians who lay in ambush, and four were killed, four drowned, and the rest put to flight.

_______________________________________________________

The following is the official report of this expedition:

I, and Thomas Forster, Esq., Mrs. Harris, and Mr. McKee, with upwards of forty men, went up the 2d inst., (October, 1755) to Captain McKee, at New Providence, in order to bury the dead, lately murdered on Mahahony Creek; but understanding the corpse were buried, we then determined to return immediately home. But being urged by John Sekalamy, and the Old Belt, to go up to see the Indians at Shamokin [now Sunbury], and know their minds, we went on the 24th, and staid there all night — and in the night I heard some Delawares talking — about twelve in number — to this purpose: “What are the English come here for?” Says another: “To kill us, I suppose; can we then send off some of our nimble young men to give our friends notice that can soon be here?” They soon after sang the war song, and four Indians went off in two canoes, well armed — the one canoe went down the river, and the other across.

On the morning of the 25th, we took our leave of the Indians, and set off homewards, and were advised to go down the east side of the river, but fearing that a snare might be laid on that side, we marched off peaceably on the west side, having behaved in the most civil and friendly manner towards whem while with them; and when we came to the mouth of the Mahahony creek, we were fired on by a good number of Indians that law among the bushes; on which were were obliged to retreat, with loss of several men; the particular number I cannot exactly mention; but I am positive that I saw four fall, and one man struck with a tomahawk on the head in his flight across the river. As I understand the Delaware tongue, I hear several of the Indians that were engaged against us, speak a good many words in that tongue during the action.

Adam Terrance

The above declaration was attested by the author’s voluntary qualification, no magistrate being present, at Paxton, this 26th October 1755, before us:

John Elder, Michael Graham, Michael Teaff, Thomas Black, Samuel Pearson, Thomas McArthur, Alexander McClure, William Harris, Samuel Lenes, William McClure

N. B. Of all our people that were in the action, there but nine that are yet returned.

______________________________________________

Conrad Weiser, an Indian interpreter and a prominent man in the province, thus writes to James Read, Esq.,, of reading, about this period.

Heidleberg, October 26, at 11o’clock Sunday night, 1755

Loving Friend:

About an hour ago I received the news of the enemy having crossed the Susquehanna, and killed a great many people, from Thomas McKee‘s down to Hunter’s Mill.

Mr. elder, the minister of Paxton, wrote to another Presbyterian minister, in the neighborhood of Adam Reed, Esq., that the people were then in a meeting, and immediately desired to get themselves in readiness to oppose the enemy, and lend assistance to their neighbors. Mr. Reed sent down to Tulpehocken, and two men, one that came from Mr. Reed’s, are just now gone, that brought in the melancholy news. I have sent out to alarm the townships in this neighborhood, and to meet me early in the morning, at Peter Spicker‘s, to consult together what to do, and to make preparations to stand the enemy, with the assistance of the Most High.

I wrote you this that you man have time to consult with Mr. Seely, and other well-wishers of the people, in order to defend our lives and others. For God’s sake let us stand together, and do what we can, and trust to the hand of Providence. Perhaps we must, in this neighborhood.

Pray, let Sammy have a copy of this, or this draft for his Honor, the Governor. I have sent him, about three hours ago, express to Philadelphia, and he lodges at my son Peter’s. Despatch him as early as you can. I pray, beware of confusion; be calm, you and Mr. Seely, and act the part of fathers of the people. I known you are both able; but excuse me for giving you this caution — time requires it. I am, dear sir,

Your very good friend and humble servant,

Conrad Weiser

__________________________________________

The near approach of the enemy created the utmost consternation among the outer settlements. The only safety was to flee and leave all to the enemy. They had in vain looked for effectual relief from the colonial government. Homes that had been occupied; barns filled with the fruits of a rich and plenteous harvest; newly sowed fields, standing corn, and cattle, sheep, etc., were all abandoned by the hardy and industrious frontier settlers, in order to save themselves from being cut off by the barbarous enemy. Even John Harris and his family were threatened with death, as stated by Mr. Harris himself in the following letter:

Paxton, October 29, 1755

Sir:

We expect the enemy upon us every day, and the inhabitants are abandoning their plantations, being greatly discouraged at the approach of such a number of cruel savages, and no present sign of assistance. I had a certain account of fifteen hundred French and Indians being on the march against us and Virginia, and now close upon our borders, their scouts scalping our families at Shamokin, desired me to take care, that there was a party of forty Indians, o9ut many days , and intended to burn my house and destroy myself and family. I have this day cup loop-holes in my house, and am determined to hold out to the last extremity, if I can get some men to stand by me. But few can be had at present, as every one is in fear of his own family being cut off every hour. Great part of the Susquehanna Indians are no doubt actually in the French interest, and I am informed that a French officer is expected at Shamokin [Sunbury] this week, with a party of Delawares and Shawanese, no doubt to take possession of our river. We should raise men immediately to build a fort up the river to take possession, and to induce some Indians to join us. We ought also to insist on the Indians to declare for or against us, and as soon as we are prepared for them we should bid up their scalps, and keep our woods full of our people upon the scout, else they will ruin our province, for they are a dreadful enemy. I have sent out two Indian spies to Shamokin; they are Mohawks.

Sir, yours, &c.,

John Harris

Edward Shippen, Esq.

___________________________________________

In the latter part of October, 1755, the enemy again appeared in the neighborhood of Shamokin [Sunbury], and in November of that year they committed several murders upon the whites under circumstances of great cruelty and barbarity. Not only the settlers on the immediate frontier, but those residing far towards the interior, were kept in constant alarm, as will be seen by the following address, or appeal, to the inhabitants of the province, issued from the present site of Harrisburg:

Paxton, October 31, 1755

(From John Harris, at 12 P. M.)

To all His Majesty’s subjects in the Province of Pennsylvania, or elsewhere:

Whereas, Andrew Montour, Belt of Wampum, two Mohawks, and other Indians, came down this day from Shamokin [Sunbury], who say the whole body of Indians, of the greatest part of them in the French interest, is actually encamped on this side of George Gabriel’s [about thirty miles north of Harrisburg, on the west side of the river], near Susquehanna, and we may expect an attack within three days at farthest; and a French fort to be begun at Shamokin in the ten days hence. Tho’ this be the Indian report, we, the subscribers, do give it as our advice, to repair immediately to the frontiers with all our forces, to intercept their passage into our country, and to be prepared in the best manner possible for the worst events.

Witness our hands:

James Galbraith, John Allison, Barney Hughes, Robert Wallace, John Harris, James Pollock, James Anderson, William Work, Patrick Henry.

P. S. — They positively affirm that the above named Indians discovered a party of the enemy at Thomas McKee‘s upper place on the 30th of October last.

Mona-ca-too-tha, The Belt, and other Indians here, insist upon Mr. Weiser’s coming immediately to John Harris‘ with his men and to counsel with the Indians.

Before me.

James Galbreath

____________________________________________

Fortunately, the reports conveyed in Mr. Harris’ letter, as well as in the above address, proved to be premature, the enemy confining his depredations to the regions of the Susquehanna, about Shamokin [Sunbury], and the Great or Big Cove, in the western part of Cumberland County, a detailed account of which would not come within our province to write.

It was not until the middle of the following year that the Indians, incited, and in some instances officered, by their allies, the French, extended their incursions into the interior of the colony, and imagination fails to conceive the peril and distress of the settlers of Paxton, Hanover, and other townships then in Lancaster (now Dauphin and Lebanon Counties). Some idea, however, may be formed of their condition from the subjoined letters.

Derry Township, 9th August, 1756.

Dear Sir:

There is nothing but bad news every day. Last week there were two soldiers killed and one wounded about two miles from Manady Fort; and two of the guards that escorted the batteaus were killed; and we may expect nothing else daily, if no stop be put to these savages. We shall all be broken in upon in these parts. The people are going off daily, leaving almost all behind them; and as for my part, I think a little time will lay the country waste by flight, so that the enemy will have nothing to do but take what we have worked for.

Sir, your most humble servant,

James Galbreath.

Ed. Shippen, Esq.

___________________________________________

Derry Township, 10th August, 1756

Honored Sir:

There is nothing her, almost every day, but murder by the Indians in some parts or other. About five miles above me, at Manada Gap, there were two of the Province soldiers killed and one wounded. There were but three Indians, and they came in among ten of our men and committed the murder and went off safe. The name, or sight of an Indian, makes almost all in these parts tremble — their barbarity is so cruel where they are masters; for, by all appearance, the devil communicates, God permits, and the French pay, and by that the back parts, by all appearance, will be laid waste by flight, with those who are cone and going; more especially Cumberland County.

Pardon my freedom in this wherein I have done amiss.

Sir, your most humble servant,

James Galbraith.

_________________________________________________

The above murders are corroborated by the following:

Hanover, August 7, 1756.

Sir:

Yesterday Jacob Ellis, a soldier of Capt. Smith’s, at Brown’s, about two miles and a half over the first mountain, just within the Gap, having some wheat growing at that place, prevailed with his officers for some of the men to help him to cut some of the grain; accordingly ten of them went, set guards and fell to work. At about ten o’clock they had reaped down, and went to the head to begin again; and, before they had all well begun, three Indians, having crept up to the fence, just behind the,. fired upon them and killed the Corporal, and another who was standing with a gun in one hand and a bottle in the other, was wounded; his left arm broken in two places, so that his gun fell, he being a little more down the field than the rest. Those who were reaping, had their fire-arms about half-way down the field, standing at a large tree. As soon as the Indians had fired, and without loading their guns, they leaped over the fence right in amongst the reapers — one of them had left his gun on the outside of the field — they all ran promiscuously, while the Indians were making a terrible haloo, and looked more like the devil than Indians. The soldiers made for their fire-arms, the Indian that came wanting his gun, came within a few yards of them and took up the wounded soldier’s gun, and would have killed another, had not one perceived him, fired at him, so that he dropped the gun. The Indians fled, and in going off, two soldiers standing about a rod apart, an Indian ran through between them, they both fired at him, yet he escaped. When the Indians were over the fence, a soldier fired at one of them, upon which he stooped a little — the three Indians escaped. Immediately after leaving the field, they fired one gun and gave a haloo. The soldiers hid the one that was killed, went home to the fort, found James Brown who lives in the fort, and one of the soldiers missing.

The Lieutenant accompanied by some more, went out and brought in the dead man; but still Brown was missing. Notice was given on that night; I went up next morning with some hands. Capt. Smith had sent up more men from the other fort; these men went out next morning; against I got there, word was come in that they had found James Brown, killed and scalped. I went over with them to bring him home. He was killed with the last shot, about twenty rods from the field — his gun, his shoes and jacket carried off. The soldiers who found him said they tracked the three Indians to the second mountain, and they found one of the Indians’ guns a short distance from Brown’s corpse, as it had not been worth much. They showed me the place where the Indians fired through the fence, and it was just eleven yards from the place where the dead man lay. The rising ground above the field, was clear of standing timber and the grubs low, so that they kept a look out.

The above account you may depend on. We have almost lost all hopes of everything, but to move off and lose our crops that we have cut with so much difficulty.

I am your Honor’s servant,

Adam Reed.

To Edward Shippen, Esq., at Lancaster.

______________________________________________

Some time in the latter part of October, the Indians again visited Hanover Township, where they murdered, under circumstances of much cruelty, several families, among whom was one Andrew Berryhill. on the 22d of October, they killed John Craig and his wife, scalped them both, burned several houses, and carried off Samuel Ainsworth, a lad about thirteen years old. The next day they scalped a German, whose name has not been given.

From entries made in their duplicates by the tax collectors of east Hanover and West Hanover Townships for the year 1756, it is shown that the following settlers had fled from their houses in that year. The whole duplicate contains the names of about one hundred taxables. The names of those who deserted their “clearings,” in East Hanover, now principally in Lebanon County, have come down to us as follows:

Andrew Karsnits, John Gilliland, John McCulloch, Walter McFarland, Robert Kirkwood, William Robeson, Valentine Staffolbeim, Andrew Clenan, Rudolph Fry. Peter walmer, John McCulloch, James rafter, Moses Vance, John Bruner, Frederick Noah, Jacob Moser, Philip Maurer, Barnhart Bashore, Jacob Bashore, Matthias Bashore, William McCulloch, Philip Colp, Casper Yost. Conrad Clerk, Christian Albert, Daniel Moser, John McClure, John Anderson, Thomas Shirley, James Graham, Barnet McNett, Andrew Brown, William Brown, Andrew McMahon, Thomas Hume, Thomas Streau, John Hume, Peter Wolf, Henry Kuntz, William Watson, John Stewart, John Porterfield, David Strean, John Strean, Andrew McGrath, James McCurry, Conrad Rice, Alexander Swan, John Green.

In West Hanover, all of which is in the present limits of this county [Dauphin County], we have a lost of those driven from their farms, containing the following, which is as complete as possible:

John Gordon, Richard Johnston, Alexander Barnet, James McCaver, Robert Porterfield, Philip Robeson, John Hill, Thomas Bell, Thomas Maguire, William McCord, Robert Huston, Benjamin Wallace, William Bennett, Bartholomew Harris, John Swan, James Bannon, William McClure, Thomas McClure, John Henry, James Riddle, Widow Cooper, David Ferguson, Widow DeArmond, James Wilson, Samuel Barnett, James Brown, Widow McGowen, Samuel Brown, Thomas Hill, James Johnston (killed).

________________________________________

Adam Reed, under date of Hanover, October 14, 1756, thus addresses Edward Shippen and others , on the situation of affairs in his neighborhood:

Friends and Fellow Subjects:

I send you in a few lines, the melancholy condition of the frontiers of this county. Last Tuesday, the 12th inst. [October 12, 1756], ten Indians came to Noah Frederick while ploughing, killed and scalped him, ad carried away three of his children that were with him — the oldest but nine years old — and plundered his house, and carried awat everything that suited their purpose; such as clothes, bread, butter, a saddle, and a god rifle gun, &c., it being but two short milers to Capt. Smith’s fort at Swatara Gap, and a little better than two miles from my house.

Last Saturday evening an Indian came to the house of Philip Robeson, carrying a green bush before him — said Robeson’s son, being on the corner of his fort, watching others that were dressing flesh by him; the Indian perceiving that he was observed, fled; the watchman fired, but missed him; this being about three-fourths of a mile from Manady Fort; — and yesterday morning, two miles from Smith’s Fort at Swatara, Mt. Bethel Township, as Jacob Farnw3ell was going from the house of Jacob Meylin to his own, was fired upon by two Indians and wounded, but escaped with his life; — and a little after, in said township, as Frederick Hewly and Peter Sample were carrying away their goods in wagons, were met by a parcel of Indians and all killed, lying dead in one place, and one man at a little distance. But what more has been done, has not come to my ears — only that the Indians were continuing their murders.

The frontiers [people] are employed in nothing else than carrying off their effects, wo that some miles are now waste. We are willing, but not able, without help — you are able, if you be willing, (that is, including the lower parts of the county,) to give such assistance as will enable us to recover our waste land. You may depend upon it, that, without assistance, we, in a few days will be on the wrong side of you; for I am now on the frontier, and, and I fear that by to-morrow night I will be left two miles.

Gentlemen: Consider what you will do, and don’t be long about it; and don’t let the world say that we died as fools died! Our hands are not tied, but let us exert ourselves and do something for the honor of our country and the preservation of our fellow subjects. I hope you will communicate our grievances to the lower part of our county, for surely they will send us help, if they understood our grievances.

I would have gone down myself, but dare not; my family is in such danger. I expect an answer by the bearer, if possible.

I am, gentlemen,

Your very humble servant,

Adam Reed.

Edward Shippen and others.

P. S. — Before sending this away, I have just received information that there are seven killed and five children scalped alive, but have not the account of their names.

___________________________________________

May 16, 1757. Eleven persons killed at Paxton by the Indians.

August 19, 1757. Fourteen people killed and taken from Mr. Finley’s congregation, and one man killed near Harris Ferry, (now Harrisburg). At this period negotiations for peace commenced with the powerful chieftain of the Delaware and Shawanese tribes, when the barbarities of the Susquehanna Indians somewhat abated. But the French, and western Indians, still roamed in small parties over the country, committing many depredations.

The following extracts are from the Pennsylvania Gazette, of 1757:

We hear from Lancaster, that six persons were taken away by the Indians, from Lancaster County, on the 17th August.

________________

Since our last, we learn from Lancaster, that there was nothing but murdering and capturing among them by the Indians. That of the 17th of August, one Beatty was killed in Paxton — that the next day James Mackey was murdered in Hanover, and William Barnett and Joseph Barnett wounded. That on the same day were taken prisoners a son of James Mackey, a son of Joseph Barnett, Elizabeth Dickey and her child, and the wife of Samuel Young and her child, and that ninety-four men, women and children were seen flying from their places in one body, and a great many more in smaller parties. So that it was feared the settlements would be entirely forsaken.

________________

Our accounts in general from the frontiers, are most dismal; all agree that some of the inhabitants are killed or carried off — houses burned and cattle destroyed daily — and at the same time, they are afflicted with severe sickness and die fast. So that in many places, they are neither able to defend themselves when attacked, nor to run away.

A letter from Hanover Township, dated October 1st, 1757, says that the neighborhood is almost without inhabitants, and on that day, and the day before, several creatures were killed by the enemy in Hanover.

On the 25th of November, Thomas Robeson and a son of Thomas Bell were killed and scalped by the Indians in Hanover Township; but the Indians immediately went off after committing other murders.

The following letter was written to Governor Denny by the commandant at Fort Hunter, a few miles north of the present site of Harrisburg:

Fort Hunter, the 3d of October, 1757.

May it please Your Honor:

In my coming back from ranging the frontiers, on Saturday, the 3d inst., I heard that the day before, twelve Indians were seen not far from here. As it was late and not knowing their further strength, I thought to go at day-break next morning, with as many soldiers and battaux men as I could get; but in a short time heard a gun fired off, and running directly to the spot, found the dead body of William Martin, who went into the woods to pick up chestnuts, where the Indians were lying in ambush. I ordered all the men to run into the woods, and we ranged until it got dark. The continued rain we have had, hindered me from following them. A number of the inhabitants had come here to assist in pursuing the Indians, but the weather prevented them. There were only three Indians seen by some persons who were sitting before Mr. Hunter’s door, and they way all was done in less than four minutes. That same night I cautioned the inhabitants to be on their guard; and in the morning I ranged on this side of the mountain; but the next day, my men being few in number by reason of fourteen of them being sick, I could not be long from the garrison; and it seems to me, there is a great number of the enemy on this side of the river.

The townships of Paxton and Derry have agreed to keep a guard some time in the frontier houses, from Mandy to Susquehanna; and I expect that your Honor will eb pleased to reinforce this detachment.

If these townships should break up the communication between Fort Augusta and the inhabitants, they would be greatly endangered.

I am, with great respect, etc.,

Christian Busse

We have advices, says the Pennsylvania Gazette, October 27, 1757, from Paxton:

On the 17th inst., as four of the inhabitants near Hunter’s Fort, were pulling their Indian corn, when two of then – Alexander Watt and John McKennet — were killed and scalped, their heads cut off; the other two scalped. That Captain Work of the Augusta regiment, coming down with some men from Fort Halifax (the present site of the town of Halifax), met the savages on Peter’s Mountain, about twenty of them, when they fired upon him at about forty yards distance; upon which his party returned the fire and put the enemy to flight, leaving behind them five horses, with what plunder they had got; and that one of the Indians was supposed to have wounded by the blood that was seen in their tracks. None of Captain Work’s men were hurt.

_____________________________________________________

The treaty of peace and friendship between the English and Indians, at Easton in 1758, in some measure calmed the apprehensions of the people, and for a time the settlers of this region enjoyed a period of rest. But the English and French were still at war, and cruel murders still continued among the outer to the close of, and after, the war of 1762. The Shawanese, a ferocious southern tribe of Indians, had formed a secreat confederacy with the tribes on the Ohio and its tributary waters, to attack simultaneously all the English posts and settlements on the frontiers. Their plan was deliberately and skillfully projected. The border settlements were to be invaded during harvest; the men, corn and cattle were to be destroyed, and by thus cutting off the supplies, the out-posts were to be reduced by famine. In accordance with this plan, the Indians fell suddenly upon the traders, whom they had invited among them. — Many of these they murdered, and plundered others of their effects, to a great value. The frontiers of Pennsylvania were again overrun by scalping parties, marking in their hostile incursions the way with blood and devastation. The upper part of Cumberland County, and parts of the present territory of dauphin County, was overrun by savages in 1763, who set fire to houses, barns, corn, hay and everything that was combustible; and some of the inhabitants were surprised and murdered with the utmost cruelty and barbarity.

This well matured onslaught by the Indians, drove the whites to acts of desperation, which only find extenuation from the circumstances, that there were no limits to the atrocities of the savages. Wherever they went, murder and cruelty marked their path, and even professed friendly Indians had fallen under strong suspicions as being, to some extent, concerned in these foul murders.

Jonas Seely, Esq., writing from Reading, September 11, 1763, said:

We are all in a state of alarm. Indians have destroyed dwellings and murdered, with savage barbarity, their helpless occupants, even in the neighborhood of Reading. Where these Indians come from and are going, we know not. Send us an armed force to aid our rangers of Lancaster and Berks.

In another letter from the same gentleman, dated Reading, September, 1763, he writes:

It is a matter of wonder that the Indians, living among us for numbers of years, should suddenly become grum friends, or most deadly enemies. Yet there is too much reason for suspicion. The rangers sent in word that these savages must consist of fifty, who travel in companies of from five to twenty, visiting Wyalusing, Wichetunk, Nain, Big Island, and Conestoga, under the mark of friendly Indians. our people have become almost infuriated to madness. These Indians were not even suspected of treachery, such had been the general confidence in their fidelity. The murders recently committed, are of the most aggravated description.

Similar suspicions of treachery among the professed friendly Indians, alluded to in the above letter, had long been prevalent among the settlers of Paxton and Donegal Township. It was strongly believed by them, that the perpetrators of many of the atrocious murders were harbored, if not encouraged and assisted, by a settlement of friendly Indians at Conestoga, now, as then, in Lancaster County. A deadly animosity was thus raised among the people of Paxton and adjoining townships, against all of Indian blood, and against the Quakers and Moravians — who were disposed to conciliate and protect the Indians — frequently, as the Paxton men thought, at the expense of the lives of the settlers

This feeling among the settlers, finally led to the massacre of the Indians at Conestoga Manor, on the night of the 14th of December, 1763. The accounts of this affair, and of similar murders of defenceless Indians in the prison at Lancaster, on the 27th of December of the same year, are so various and conflicting, that it is almost impossible to form an intelligent historic narrative of them. The act was most probably committed by the younger and more hot-blooded members of the Rev. Col. Elder’s corps of rangers, led by Capt. Lazarus Stewart, a daring partisan, and a man of considerable influence and standing in the Paxton settlement. He soon afterwards joined the Connecticut men, and became very conspicuous in the civil wars of Wyoming. He was once taken prisoner there, and delivered to the Sheriff of York County for safe-keeping; but his rangers rescued him, and he suddenly appeared again with many of them at Wyoming. He was slain near Wilkesbarre [Wilkes-Barre], during the revolution, in the disastrous battle of 3d July, 1778.

The following extracts are from a series of historical papers in the Lancaster Intelligencer & Journal of 1843, written by Redmond Conyngham, Esq.:

Imagination cannot conceive the perils with which the settlement of Paxton was surrounded from 1754 to 1765,. To portray each scene of horror would be impossible — the heart shrinks from the attempt. The settlers are goaded on to desperation; murder followed murder. The scouts brought in the intelligence that the murderers were traced to Conestoga. rifles were loaded and horses were in readiness. They mounted; they called on their pastor to lead them. he was the in the 57th year of his age. Had you seen him then, you would have beheld a superior being. He had mounted, not to lead them on to the destruction of Conestoga, but to deter them from the attempt: he implored them to return; he urged them to reflect: “pause, pause before you proceed!” It was in vain: “The blood of the murdered cries aloud for vengeance; we have waited long enough on Government; the murderers are within our reach, and they must not escape.” Mr. Elder reminded them, that “the guilty and innocent could not be distinguished.” “Innocent!” can they be called innocent who foster murderers?” Mr. Elder rode up in front, and said: “As your pastor, I command you to relinquish your design.” “Give way then,” said Smith, “or your horse dies,” presenting his rifle. To save his horse, to which he was much attached, Mr. Elder drew him aside, and the rangers were off on their fatal errand.

The following narrative was drawn up by Matthew Smith, one of the chief actors in the massacre:

I was an early settler in Paxton, a member of the congregation of the Rev. Mr. Elder. I was one of the chief actors in the destruction of Conestoga, and in storming the work-house in Lancaster. I have been stigmatized as a murderer. No man, unless he were living at the time in Paxton, could have an idea of the sufferings and anxieties of the people. For years the Indians had been on the most friendly terms; but some of the traders were bought by the French; these corrupted the Indians. The savages unexpectedly destroyed our dwellings and murdered the unsuspicious. When we visited the wigwams in the neighborhood, we found the Indians occupied in harmless sports, or domestic work. There appeared to be no evidence that they were in any way instrumental in the bloody acts perpetrated on the frontiers.

Well do I remember the evening when —– —– stopped at my door; judge my surprise when I heard his tale: “Tom followed the Indians to the Big Island; from thence they went to Conestoga; as soon as we heard it, five of us, —–, —–, —–, ——, —–, rode off for the village. I left my horse under their care, and cautiously crawled where I could get a view; I saw Indians armed; they were strangers; they outnumbered us by dozens. I returned without being discovered. We meet tonight at —–; we shall expect you with gun, knife and amunition [sic].” We met, and our party, under cover of the night rode off for Conestoga. Our plan was well laid; the scout who had traced the Indians, was with us; the village was stormed and reduced to ashes. The moment we were perceived an Indian fired at us, and rushed forward, brandishing his tomahawk. Tom cried, “mark him,” and he fell by more than one ball, —– ran up and cried: “It is the villain who murdered my mother.” This speech roused to vengeance, and Conestoga lay harmless before us. our worst fears had been realized; these Indians, who had bee housed and fed as the pets of the Province, were now proved to be our secret foes; necessity compelled us to do as we did. We mounted our horses and returned. Soon were were informed, that a number of Indians were in the workhouse at Lancaster. —– was sent to Lancaster to get all the news he could. He reported that one of the Indians concerned in recent murders was there in safety. Also, that they talked of rebuilding Conestoga, and placing these Indians in the new buildings.

A few of us met to deliberate; Stewart proposed to go to Lancaster, storm their castle, and carry off the assassin. It was agreed to; the whole plan was arranged. Our clergyman did not approve of our proceeding further. He thought everything was accomplished by the destruction of Conestoga, and advised us to try what we could do with the Governor and Council. I, with the rest, was opposed to the measure proposed by our good pastor, it was painful to us to act in opposition to his will, but the Indian in Lancaster was known to have murdered the parent of —–, one of our party.

The plan was mare; three were chosen to break in the doors; five to keep the keepers, &c., from meddling; Captain Stewart to remain outside with about twelve men, to protect those within, to prevent surprise and keep charge of the horses. The three were to secure the Indian, tie him with strong cords, and deliver him to Stewart. If the three were resisted, a shot was to be fired as a signal. I was one of them who entered; you know the rest; we fired; the Indians were left without life; and we rode hastily from Lancaster.

This gave quiet to the frontiers, for no murder of our defenceless inhabitants has since happened.

Matthew Smith, the writer of the above, after the revolution, in which he performed excellent service and rose to high rank in military and civil life, removed to Milton, Northumberland County.

___________________________________________

A letter of the Rev. Mr. Elder to Governor Penn, January 27, 1764, states:

The storm which had been so long gathering , has at length exploded. Had Government removed the Indians from Conestoga, which had frequently been urged without success, this painful catastrophe might have bee avoided. What could I do with men heated to madness? All that I could do, was done. I expostulated: but life and reason were set at defiance. And yet, the men, in private life, are virtuous and respectable; not cruel, but mild and merciful.

The time will arrive, when each palliating circumstance will be calmy weighed. This deed, magnified into the blackest of crimes, should be considered as one of those youthful ebulitions of wrath caused by momentary excitement, to which human infirmity is subjected.

__________________________________________

In connection with this subject an extract from a remonstrance presented to Governor John Penn, from the inhabitants of Lancaster County, is quoted:

We consider it a grievance, that we are restrained from electing more than ten representatives in the frontier counties — Lancaster four, York two, Cumberland two, Berks one, Northampton one — while the city and county of Philadelphia, and the counties of Chester and Bucks, elect 26. A bill is now about to be passed into a law, that any person accused of taking away the life of an Indian, shall not be tried in the county where the deed was committed, but in the city of Philadelphia. We can hardly believe the Legislature would be guilty of such injustice as to pass this bill, and deprive the people of one of their most valuable rights. We protest against the passage of such a law, as depriving us of a sacred privilege.

We complain that the Governor laid before the General Assembly letters without signatures, giving exaggerated and false accounts off the destruction of the Indians at Conestoga, and at Lancaster. That he paid but little attention to the communications received from our representatives and Mr. Shippen; that certain persons in Philadelphia are endeavoring to rouse the fury of the people against the magistrates, the principal inhabitants of the borough of Lancaster, and the Presbyterians of Paxton and Donegal, by gross misrepresentations of facts; that we are not allowed a hearing at the bar of the House, or by the Governor; that our rangers have never experienced any favors from Government, wither by remuneration of their services, or by any act of kindness; that although there is every reason to believe that the Indians who struck the blow at the Great Cove, received their arms and amunition [sic] from the Bethlehem Indians, Government protects the murderers at Philadelphia; that six of the Indians now in Philadelphia, known to have been concerned in recent murders, and demanded by us, that they might be tried in Northampton County, are still at liberty; that Renatus, an Indian was legally arrested and committed on the charge of murder, is under the protection of government in Bucks County, when he was to be brought to trial in the county of Northampton, or the county of Cumberland. Shall these things be?

Matthew Smith, James Gibson

____________________________________________

The following document, printed at the time, is interesting in this connection:

“DECLARATION. LET ALL HEAR!”

Were the counties of Lancaster, York, Cumberland, Berks and Northampton protected by Government? Did not John Harris, of Paxton, ask advice of Co. Croghan, and did not the Colonel advise him to raise a company of scouters, and was not this confirmed by Benjamin Franklin? And yet, when Harris asked the Assembly to pay the scouting party, he was told that he might pay them himself. Did not the counties of Lancaster, York, Cumberland, Berks and Northampton, the frontier settlements, keep up rangers to watch the motions of the Indians; and when a murder was committed by an Indian, a runner with the intelligence was sent to each scouting party, that the murderer or murderers might be punished? Did we not brave the summer’s heat and the winter’s cold, and the savage tomahawk, while the inhabitants of Philadelphia, Philadelphia County, Bucks and Chester “ate, drank and were merry.”

If a white man kill an Indian, it is a murder far exceeding any crime upon record; he must not be tried in the county where he lives, or where the offence was committed, but in Philadelphia, that he may be tried, convicted, and sentenced and hung without delay. If an Indian kill a white man, it was the act of an ignorant heathen, perhaps in liquor; alas, poor innocent! — he is sent to the friendly Indians, that he may be made a Christian. Is it not a notorious fact, that an Indian who treacherously murdered a family in Northampton County, was given up to the magistrates, that he might have a regular trial; and was not this Indian conveyed into Bucks County, and is he not provided with every necessary, and kept secured from punishment by Israel Pemberton? Have we not repeatedly represented that Conestoga was a harbor for prowling savages, and that we were at loss to tell friend or foe, and all we asked was the removal of the Christian Indians? Was not this promised by Governor Penn, and yet delayed? Have we forgotten Renatus, that Christian Indian? A murder of more than savage barbarity was committed on the Susquehanna; the murderer was traced by the scouts to Conestoga; he was demanded, but the Indians assumed a warlike attitude, tomahawks were raised, and the fire-arms glistened in the sun; shots were fired upon the scouts, who went back for additional force. They returned, and you know the event — Conestoga was reduced to ashes. But the murderer escaped. The friendly and unfriendly were placed in the workhouse at Lancaster. What could secure them from the vengeance of an exasperated people? The doors were forced, and the hapless Indians perished. Were we tamely to look on and see our brethren murdered, and see our fairest prospects blasted, while the inhabitants of Philadelphia, Philadelphia County, Bucks and Chester, slept and reaped their grain in safety?

These hands never shed human blood. While am I singled out as an object of persecution? Why are the bloodhounds let loose on me? Let him who wished to take my life — let him come and take it. I shall not fly. All I ask is, that the men accused of murder be tried in Lancaster County. All I ask is a trial in my own county. If these requests are refused, then not a hair of those men’s heads shall be molested. Whilst I have life, you shall not either have me, or them, on any other terms. It is true. I submitted to the sheriff of York County, but you know too well that I was to be conveyed to Philadelphia like a wild felon — manacled — to die a felon’s death. I would have scorned to fly from York, I could not bear that my name should be marked by ignomy. What I have done, was done for the security of hundreds of settlers on the frontiers. The blood of a thousand of my fellow creatures called for vengeance. I shed no Indian’s blood. As a ranger I sought the post of danger, and now you ask my life. Let me be tried where prejudice has not prejudged my case. Let my brave rangers, who have stemmed the blast nobly and never flinched — let them have an equitable trial; they were my friends in the hour of danger — to desert them now, were cowardice. What remains, is to leave our cause with our God, and our guns.

Lazarus Stewart

____________________________________________________

When the news of the transactions at Conestoga and Lancaster reached Philadelphia, the authorities removed the savages confined on Province Island, to the barracks in that city for greater safety. This was deemed necessary from the fact that large delegations of the frontier inhabitants, who determined that the Assembly should redress their grievances, were marching on Philadelphia, and whose hatred for the Indians was intense. This demonstration produced much alarm, in the city, as all sorts of rumors were afloat as to the objects of the settlers. The Governor fled to the house of Dr. Franklin, and unnecessary military measures were taken to repel the so-called insurgents. Finding that the excitement was great, upon consultation among themselves, the majority of the Paxtonians concluded to return to their houses in Lancaster and Cumberland counties, leaving Smith and Gibson to to represent them in the real object of the march on Philadelphia — a redress of grievances.

At various periods between 1752 and 1760 the Provincial Government erected a line of forts between the Delaware River and the Potomac. Of these Fort Hunter, Fort Manada, Fort Brown, and Fort Halifax, were in the territory which subsequently became the county of Dauphin.

Fort Hunter, which seems to have been of considerable importance, was situated at the mouth of fishing Creek, about five miles north of Harrisburg. The spot was originally settled by the Chambers, but is now [1876] well known as “McAllisters.”

The precise locality of this fort is not known. According to a letter of Edward Shippen, Esq., dated April 19, 1756, it stood five or six hundred feet from Hunter’s house. It was surrounded by an entrenchment, which, however, seems to have been leveled in 1763. Rev. John Elder, who was also a colonel, writing to Gov. Hamilton, says:

I have always kept a small party of men stationed at Hunter’s, still expecting that they would have been replaced by 17 or 20 of the Augusta troops, as your honor was pleased once to mention; and if that point is destined to be maintained, as the entrenchment thrown up there in the beginning of the late troubles, is now level with ground, it will be absolutely necessary to have a small stockade erected there to cover the men, which may be done at an inconsiderable expense.

________________________________________

According to the Commissary General’s returns, in November, 1756, the state of the garrison at Fort Hunter was as follows:

2 sergeants, 34 privates; ammunition — 4 pounds of powder, 28 pounds of lead; provisions — 1,000 weight of flour, 2,000 pounds of beef; 2 men’s time up.

________________________________________

In August, 1757, in a petition to the Provincial Council the inhabitants of Paxton set forth:

that the evacuation of Fort Hunter is of great disadvantage to them; that Fort Halifax is not necessary to secure the communication with Fort Augusta, and is not so proper a station for the batteaux parties as Fort Hunter; pray the governor would be pleased to fix a sufficient number of men at Hunter’s under the command of an active officer, with strict orders to range the frontiers daily.

______________________________________

The Rev. John Elder backed this petition with the following letter to Richard Peters, Secretary of Council:

Paxton, 30th July, 1757.

Sir:

As we of this township have petitioned the Governor for a removal of the garrison from Halifax to Hunter’s, I beg the favor of you to use your interest with his honor in our behalf. The defence of Halifax is of no advantage; but a garrison at Hunter’s under the command of an active duty officer, will be of great service; it will render the carriage of provisions and ammunition for the use of Augusta more easy and less expensive; and by encouraging the inhabitants to continue in their places, will prevent the weakening of the frontier settlements. We have only hinted at these things in the petition, which you will please t enlarge on in conversation with the Governor, and urge in such a manner as you think proper. ‘Tis well known that representatives from the back inhabitants have but little weight with the gentlemen in power, they looking on us wither as incapable of forming just notions of things, or as biased by selfish views. However, I am satisfied that you, sir, have more favorable conceptions of us; and that from the knowledge you have of the situation of the places mentioned in our petition, you will readily agree with us and use you best offices with the Governor to prevail with him to grant it; and you will very much oblige.

Sir, your most obedient And humble Servant

John Elder

__________________________________________

Pending the consideration of this question in the Council, Commissary Young was called before that body. He stated

that Fort Halifax is a very bad situation, being built between two ranges of hills, and nobody living near it, none could be protected by it; that it is no station for batteaux parties, having no command of the channel, which runs close on the western shore, and is beside covered with a large island between the channel and the fort, so that numbers of the enemy may even in day time run down the river without being seen by that garrison.

He further said that though the fort or block house at Hunter’s was not tenable, being hastily erected and not finished, yet the situation was the best upon the river for every service, as well as for the protection of the frontiers.

__________________________________________

The Indians made several invasions near to Fort Hunter, and as we have already mentioned, killed a man in 1757. Bartram Galbraith says in a letter, dated Hunter’s Fort, October 1, 1757:

Notwithstanding the happy condition we thought this place in, on Capt. Busse’s being stationed here, we have had a man killed within twenty rods of Hunter’s barn. We all turned out, but night coming on soon, we could not make any pursuit.

__________________________________________

When Col. James Burd visited Fort Hunter in February, 1758, he says

he found Capt. Patterson and Levis here with eighty men. The captain informed me that they had not above three loads of ammunition to a man. I ordered Mr. Barney Hughes to send up here a barrel of powder and lead answerable. In the meantime borrowed of Thomas Gallager four pounds of powder and one hundred pounds of lead. I ordered a review of the garrison to-morrow morning at 9 o’clock.

We continue from Col. Burd’s journal:

Tuesday, 19 [February 1758]. Had a review this morning of Capt. Patterson’s company, and found them complete — fifty-three men, forty-four province arms, and forty-four cartouch boxes — no powder nor lead. I divided one-half pint of powder, and lead in proportion, to a man. I found in this fort four months’ provisions for the garrison.

Captain Davis with his party of fifty-five men, was out of ammunition. I divided one-half pint of powder and lead in proportion to them. Capt. Davis has got twelve hundred weight of flour for the batteaux. Sundry of the batteaux are leaking and must be left behind. Capt. Patterson cannot scout at present for want of officers. I ordered him to apply to the country to assist him to stockade the fort agreeable to their promise to his honor, the Governor. There are three men sick here.

________________________________________

Fort Hunter, or Hunter’s Mill, like Harris Ferry, was a great shipping point for provisions and military stores up and down the Susquehanna. As early as 1748, when Joseph Chambers resided there, the place was of some consequence. The Colonial records mention several formal “talks” with the Indians at Hunter’s Fort.

Fort Halifax was built at the mouth of Armstrong’s Creek, about half a mile above the present town of Halifax. There is nothing now [1876] to mark the place, except in a slight elevation of the ground and a well known to have belonged to the fort. The fort was built in 1756 by Col. William Clapham. in a letter to Gov. Morris, dated June 20, 1756, Col. Clapham says:

The progress already made in this fort renders it impracticable for me to comply with the commissioner’s desire to contract it, at which I was surprised, as I expected every day orders to enlarge it, it being yet, in my opinion too small. I shall have an officer and thirty men with orders to finish it when I march from hence.

In a postscript, the colonel adds:

The fort at this place is without a name till your honor is pleased to confer one.

_________________________________________

Gov. Morris replied to this letter, as follows:

Philadelphia, June 21, 1756.

The fort at Armstrong — I would have it called ‘Fort Halifax.’

_________________________________________

Col. Clapham was under orders to proceed to Shamokin [Sunbury], and previous to embarking for that post, he wrote to Governor Morris, under date of July 1, 1756, as follows:

I shall leave a sergeant’s party at Harris , consisting of twelve men, twenty-four at Hunter’s Fort, twenty-four at McKee’s store (twenty-five mile above Fort Hunter), each under the command of an ensign; and Captain Miles, with thirty men, at Fort Halifax, with the inclosed instructions, as I have removed all the stores from Harris Ferry and McKee’s to this place.

_______________________________________

The instructions to Captain Miles, above mentioned, were as follows:

Fort Halifax, July 1, 1756.

Sir:

You are to command a party of thirty men at Fort Halifax, which you are to finish with all possible expedition. observing not to suffer your party to struggle in small numbers into the woods, or to go any great distance from the fort, unless detached as an escort, or in case of special orders for that purpose. You are to build barracks within the fort for your men, and also a store house, thirty feet by twelve, in which you are carefully to lodge all your provisions, stores, &c., belonging to the province. If the board purchased for that purpose are not sufficient to finish the banquette, and execute the other designs herein recommended, your men are to be employed in sawing more out of the pine logs now lying near the fort. You are to keep a constant guard, and relieve regularly, to have continual one sentry in each bastion, and in case of attack, to retreat to the fort, and defend it to the last extremity.

If anything extraordinary occurs, you are immediately to dispatch notice thereof to his Honor, the Governor, and to signify the same to me, if any relief or instructions may be necessary.

William Clapham

__________________________________________

Besides these regular provincial forts, there were several others, built by the settlers themselves. Such were Forts Manady (near the present Manada Furnace) and Brown (near Adam Reed’s, at the “big bend” of Swatara). Some of the more substantial dwelling houses of the settlers were also converted into block-houses, and in times of danger, became rallying points for the people. The Colonial records mention several of those as existing in Hanover and Paxton Townships.

In a letter, dated October 29, 1755, John Harris writes:

I have this day cut loop-holes in my house, and am determined to hold out to the last extremity, is I can get some men to stand by me.

He subsequently strengthened his defences by erecting a stockade, which is mentioned by Edward Shippen in a letter to Governor Morris, under date of April 19, 1756. —

John Harris has built an excellent stockade around his house, which is the only place of security that way for the provisions of the army, he having much good cellar room; and as he has but six or seven men to guard it, if the Government would order six more men there to strengthen it, it would, in my opinion, be of great use t the cause.

________________________________________________

Corrections and additional information should be added as comments to this post.

[Indians]