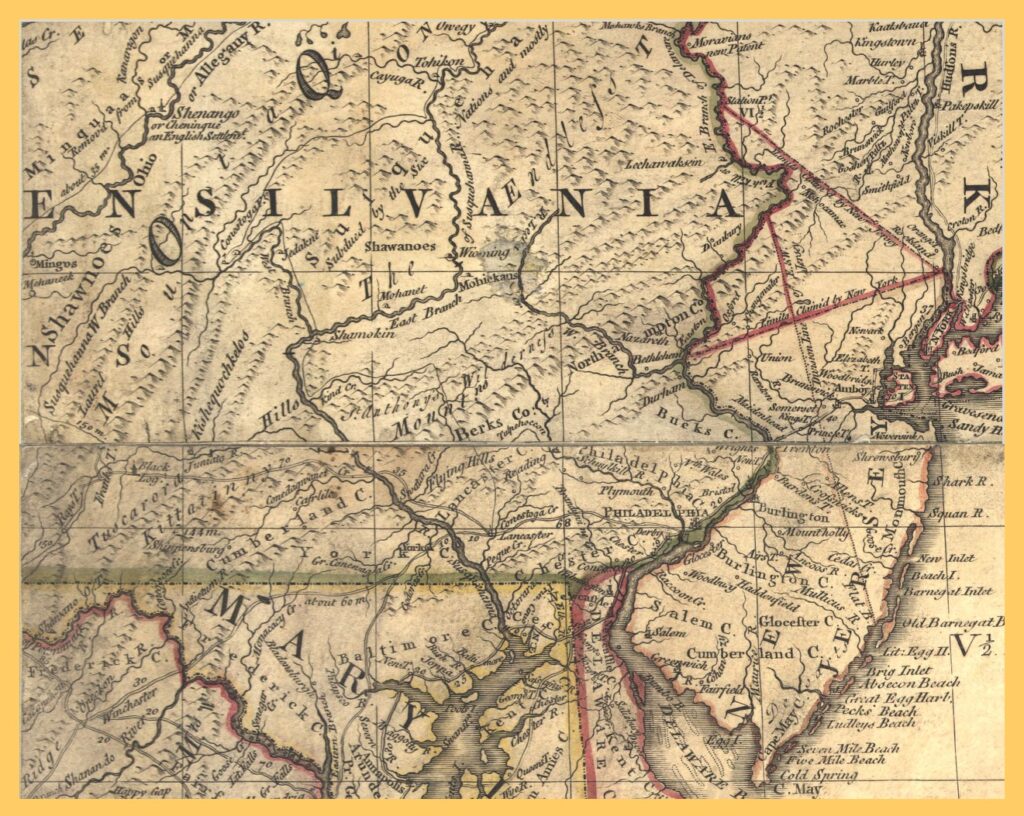

A cut from a 1755 map of British and French Dominions in North American, by John Mitchell, focusing on southeastern and south-central Pennsylvania. The map is from the collection of the Library of Congress.

Early Colonial history in the area known today as Schuylkill County, Pennsylvania, is told by Joseph H. Zerbey in Volume 4 of his History of Pottsville and Schuylkill County, beginning on page 1602. The book is available as a free download from the Internet Archive.

Today, some of the terminology used by Zerbey is considered racist, e.g., the words “savage” or “red men” to describe Indians. It is very rare in the time period that this was written to find any writings sympathetic to Indians.

Note: Tolheo means hollow in the mountain, and referred to the place where the Tulpehocken Trail crossed the mountain. This is now the route of the Millersburg or Bethel Road. Millersburg, as mentioned in the chapter, is the present town of Bethel.

______________________________

CHAPTER 3

FRENCH & INDIAN WAR

The treaty of the Aix-la-Chapelle signed October 1, 1748, nominally closed the four years of war between England and France. But this treaty did not settle the controversy between the two nations with respect to territory on the American continent. The English colonies were originally established along the seacoast. The English, therefore, claimed the right to extend their settlements inland.

The French were in possession of Canada to the north and the extensive Louisiana Territory to the south. Because of these possessions, they too, claimed the right to the intervening territory.

Both countries laid claim to the same territory, but neither party exercised their rights until England gave a grant of six hundred thousand acres of land in the disputed territory to the “Ohio Company.” This company was an association formed in Virginia, about the year 1748, under a royal grant, both to trade with the Indians, and to open the territory to settlement. Its concessions were large and conferred special privileges on the corporators.

To counteract these designs of the English, the Governor General of Canada in 1749 sent General Celeron down the Allegheny and Ohio Rivers to take possession in the name of the King of France. His command comprised 215 French and Canadian soldiers, and 55 Indians of different tribes. As they moved southward they marked points along their march with leaden plates, upon which were inscribed the date and name of the place, to assert possession.

In 1752, another expedition set out comprising 300 men under the command of Monsieur Babeer, who was succeeded in May of that year by Monsieur Morin, who arrived with 500 white men and 20 Indians.

The Governor of Virginia, alarmed by the advances of the French sent George Washington late in 1753 to demand of the French an explanation of their designs. He was told the matter would be taken up with the Governor General, but pending a decision, the French would remain in the country.

In January 1754, a company of Virginia Militia was sent into the disputed territory to cooperate with the Ohio Company in supporting its claims to the territory. They arrived at the Forks of the Ohio on February 17th and established a clearing. Their stay was short, however. On April 16, 1754, the French suddenly appeared in great force and obliged the company to surrender.

The French, determined to contest the claims of the Ohio Company, proceeded to the confluence of the Allegheny and Monongahela Rivers where they erected a fort which they named Duquesne in honor of the Governor General of Canada.

The British government immediately ordered the various governors of the provinces to resort to force in defense of their rights and to drive the French from Ohio.

The duty of carrying on active operations against the French fell upon Virginia. George Washington, having been commissioned a lieutenant colonel by Governor Dinwiddie, was sent with one hundred and fifty men to take command at the forks of the Ohio, finish the fort already started there by the Ohio Company and to resist with force all who interrupted the English settlements. With great difficulty he succeeded in reaching the Great Meadows. Learning that fifty of the enemy were in striking distance of his command, he immediately marched against them, attacked and defeated them on the morning of May 28th, 1754. When the news of the engagement reached Fort Duquesne the French organized a strong party and advanced against Washington. He built entrenchments and erected palisades, naming his stockade “Fort Necessity.” With vastly superior forces against him Washington carried on a spirited and heroic defense but was forced to capitulate. At daybreak, on the fourth of July, the garrison filed out of the Fort with all the honors of war. The English flag on the Fort was struck and the French flag took its place. Washington and his little army passed over the mountains homeward leaving the entire territory west of the Alleghenies in the possession of the French.

The French, anticipating an early campaign by the English, greatly strengthened their force at Fort Duquesne during the late fall of 1754. At one time more than one thousand regular French soldiers with several hundred Indians were in the garrison.

The British decided upon aggressive operations in the late fall of 1754. Major General Edward Braddock, was made General-in-Chief of the English forces in North America. He arrived in Virginia on the 20th of February, 1755, with two regiments of royal troops. With the addition of provincials from Virginia and Maryland, and two independent companies from New York, he started for the Ohio at the head of two thousand two hundred troops. They were well armed and supplied.

Dragging his artillery over the Allegheny mountains and marching his troops with military precision he made about three miles a day. His horses, for want of grass, weakened, and many of his men became sick as they moved along through the endless forest.

The French, learning of Braddock’s advance, induced the Indians to harass the struggling army. They not only picked off the stragglers, but carried on a border warfare against all settlers. George Washington, who accompanied Braddock, advised strongly against the cumbersome tactics of the English General, and finally prevailed upon Braddock to leave his artillery and press forward with twelve hundred men.

Braddock moved along with good discipline with scouts thrown out till he reached a ford of the Monongahela on July 8th seven miles from Fort Duquesne. The French were alarmed and could hardly prevail upon the Indians to engage the English. Finally about nine hundred, mostly Indians, under the command of Beaujeau, met Braddock’s army just after it had come out of the ford, a meeting hardly expected by either party.

The British army in solid order went forward to the attack, and the Canadian French fled and were not seen again that day. The Indians however sensed the weakness of the English position. They had the advantage of a high hill on one side and each Indian, selecting a tree or a log for cover, sent his deadly fire into the close ranks of the British. The British regulars fell thickly, but they held their position. Washington, realizing the futility of such fighting, took his provincials and protected the remnants of the fine army by fighting Indian fashion. Washington advised Braddock to adopt the same plan with the regulars, but he persisted in forming them into platoons, consequently they were cut down from behind logs and trees as fast as they could advance. Fighting continued until late afternoon of the ninth, when the remnants of the army retreated in great disorder from the field. Baggage, stores, artillery, everything was abandoned.

The shattered army continued its flight after it had crossed the Monongahela, a wretched wreck of the brilliant little force that had marched along its banks only a short time before, confident of victory.

It continued its march, until it reached the Great Meadows on the 13th, where Braddock died that night of wounds received in the battle, and was buried in the lonely wilderness.

The effect of Braddock’s defeat was staggering. The Province was wholly unprepared to resist an invading army of savages. Fifteen years before the Provincial government had petitioned the King to place the Province in a proper state of defense. A discussion of the subject was carried on continuously in the Assembly till 1744, but that body, under Quaker influence, held there was no need for such action.

On July 26, 1755, immediately upon the receipt of the news of Braddock’s defeat, Governor Morris convened the Assembly and asked for financial aid. Two days later this was granted by a bill raising fifty thousand pounds for the King’s use by a tax of twelve pence per pound and twenty shilling per head yearly for two years on all the estate, real and personal, and taxables within the Province. This included a tax on all property and greatly affected the estates of the proprietaries. Difficulty immediately arose. The Governor acting on their behalf, would not agree claiming the lands were not taxable, and being unprofitable, should not be taxed.

Benjamin Franklin, as leader of the Assembly, took sharp issue with the Governor, each accusing the other of insincerity.

During the controversy the Quakers, who cited their religious principles, worked hard to prevent an appropriation for defense purposes. Thus, both sides refused to cede a single point, until November 24, 1755, when a gift of five thousand pounds was received from the proprietaries. The Assembly then passed an amended act granting fifty-five thousand pounds, while exempting the proprietary estates from taxation.

Following Braddock’s defeat, scouts and friendly Indian runners brought the news of the English defeat to the eastern part of the colony and gave warning that bands of warring Delawares and Shawanese Indians were coming east to join with their clansmen at Shamokin in a war against the colonists.

On October 16, 1755, the Indians opened hostilities on the Susquehanna, when they suddenly fell upon the inhabitants along Mahahany or Penn’s Creek, a settlement about four miles south of Shamokin. The Provincial records state that thirteen persons were killed and twelve were either scalped or carried away.

In a petition to Governor Morris the inhabitants on the west side of the Susquehanna near the mouth of Mahanany Creek, urged speedy relief for the frontier settlements. The governor was informed “that on about the 16th, inst. (October 1755) the enemy came down upon Mahahany Creek and killed, scalped, and carried away all the men, women and children, amounting to twenty-five in number, and wounded one man, who fortunately made his escape, and brought the news, whereupon the remaining settlers went out and buried the dead, whom they found most barbarously murdered and scalped.”

Subsequent to the attack, a company of 46 inhabitants on the Susquehanna under the leadership of Capt. Thomas McKee and John Harris, the founder of Harrisburg, went to Shamokin to assist the unhappy settlers in burying the dead. On their return from Shamokin they were fired upon by Indians who lay in ambush, and four of the party were killed, four drowned, and the rest put to flight. When the news of the attack reached the people living along the Susquehanna all settlements between Shamokin and Hunter’s Mill, for a space of 50 miles were deserted.

The massacre at Penn’s Creek encouraged the Indians to move southward, and it was fear of this movement by them, that drove terror into the peaceful frontier settlements in Pine Grove and across the mountain in the Tulpehocken Region.

The new of the shocking cruelties that the Indians had inflicted upon the inhabitants of the province on their way eastward spread rapidly. Among the first to be apprised of the tragedy at Penn’s Creek was Conrad Weiser, who expressed his fear of invasion of the frontier settlements of Berks County in a letter to Governor Morris, concerning the outrage at Penn’s Creek. “The people are in great consternation,” he wrote, “and are coming down, leaving their plantations and corn behind them.”

Realizing the seriousness of the situation, Weiser immediately set about to arouse his neighborhood. He sent his servants from farmhouse to farmhouse with the news of the Penn’s Creek massacre. In response to his alarm, people started to assemble at his house early in the morning. After discussing the news of the Penn’s Creek affair, the people decided to organize and start immediately in quest of the enemy, provided Weiser assumed command. He gave them orders to go to their home and get their arms, whether guns, swords, pitchforks, axes of whatever they might have which might be of use in fighting the enemy. He also told them to bring three days’ provisions in their knapsacks, and meet him that afternoon at the place of Benjamin Spycker‘s, a justice of the peace, about six miles away.

What followed is told with great detail in a letter from Mr. Wieser to Governor Morris, dated October 27, 1755.

After sending word to the Tulpehocken folk to meet him at Benjamin Spyckers, he carefully describes what later transpired.

“I immediately mounted my horse, and went up to Benjamin Spycker‘s, where I found about one hundred persons who had met before I came there; and after I had informed them of the intelligence, that I had promised to go with them as a common soldier, and be commanded by such officers and leading men, whatever they might call them, as they should choose, they unanimously agreed to join the Heidelberg people and accordingly they went home to fetch their arms, and provisions for three days, and came again at three o’clock. All this was punctually performed; and about two hundred were at Benjamin Spycker‘s at two o’clock.

“I made the necessary disposition, and the people were divided into companies of thirty men in each company, and they chose their own officers; that is, a captain over each company, and three inferior officers under each, to take care of ten men, and lead them on, or fire as the captain should direct.

“I sent privately for Mr. Kurtz, the Lutheran minister, who lived about a mile off, who came and gave an exhortation to the men, and made a prayer suitable to the time. Then we marched toward Susquehanna, having first sent about fifty men to Tolheo, in order to possess themselves of the gaps or narrows of Swatara, where we suspected the enemy would come through. With those fifty I sent a letter to Mr. Parsons, who happened to be at his plantation.

“We marched about ten miles that evening. My company had now increased to upwards of three hundred men, mostly well armed, though about twenty had nothing but axes and pitchforks – all unanimously agreed to die together, and engage the enemy wherever they should meet them, never to inquire the number, but fight them, and so obstruct their way of marching further into the inhabited parts, till others of our brethren come up and do the same, and so save the lives of our wives and children.

“This night the powder and lead came up, that I sent for early in the morning, from Reading, and I ordered it to the care of the officers, to divide it among those that wanted it most. On the 28th, by break of day, we marched, our company increasing all along. We arrived at Adam Reed‘s, Eds., in Hanover Township, Lancaster County, (now Harpers in Lebanon County) about ten o’clock. There we stopped and rested till all came up.”

Upon reaching Mr. Reed’s home, Mr. Weiser was informed of the experience of Captain McKee, John Harris and others who had gone to Shamokin to help bury the dead at Penn’s Creek. It was promptly decided that it would be best for the men to return home and take care of their own townships. He cautioned the people to “hold themselves in readiness, as the enemy was certainly in the country, to keep their arms in good order, and so on, and then discharged them – and we marched back with the approbation of Mr. Reed. By the way, we were alarmed by a report that five hundred Indians had come over the mountain at Tolheo to this side, and had already killed a number of people. We stopped and sent a few men to discover the enemy, but on their return, it proved to be a false alarm, occasioned by that company that I hade sent that way the day before, whose guns getting wet, they fired them off, which was the cause of alarm- this not only had alarmed the company, but the whole townships through which they marched. In going back, I met messengers from other townships about Conestoga, who came for intelligence, and to ask me where their assistance was necessary, promising that they would come to the place where I should direct.

“I met, also, at Tulpehocken, about one hundred men well-armed, as to fire-arms, ready to follow we; so that there were in the whole about five hundred men in arms that day, all marching up towards Susquehanna. I and Mr. Adam Reed counted those who were with me – we found them three hundred and twenty.”

Immediately after receiving Weiser’s letter Governor Morris sent a letter to him in which he conferred upon him the commission of colonel. He wrote:

“I have the pleasure of receiving your favor of the 30th instant, and of being thereby set right as to the Indians passing the mountains at Tolheo which I am glad to find was a false alarm. I heartily commend your conduct and zeal, and hope you will continue to act with the same vigor and caution that you have already done. and that you have the greater authority, I have appointed you a colonel by a commission herewith.

“I have not time to give you any instructions with the commission but leave it to your judgment and discretion, which I know are great, to do what is most for the safety of the people and service of the crown.”

Col. Weiser with keen discernment, recognized the strategic advantages of the gaps in the mountains, and realized that if the settlers in Pine Grove Township and south of the mountain were to be protected against invasion, the gaps that commanded the Indian trails, would have to be fortified.

He made wise preparation for this on the day he started with his three hundred men on the march to the Susquehanna. He not only sent about fifty men to take possession of the Shamokin Trailcrossing the Blue Mountain, but also instructed William Parsons by messenger to meet this company and additional men at the foot of the mountain on the Shamokin Road. It was Col. Weiser’s plan to have Parsons fortify the road at the foot of the north side of the mountain with a breast-work of trees near the Lengel Farm in Pine Grove Township and the next day proceed “to the Upper Gap of Swarotawro,” (Lorberry Junction) and there make another breastwork of trees.

When Parsons met his company, he found only half of them provided with lead and powder. He urged them to go forward and arrange the defenses, while he went to Tulpehocken to get the necessary supply of ammunition. In a letter to Richard Peters, Provincial secretary on October 31, 1755, he gives an interesting account of the affair. He stated:

“Monday evening I received an express from Mr. Weiser, informing me that he had summoned the people to go and oppose the Indians, and desired me to meet a large company near the foot of the mountain in the Shamokin Road (Millersburg Road) while he went with about 300 to Paxtang. When I came to the company at the foot of the mountain, about 100 in all, I found one-half of them without any powder or lead. However, I advised them to go forward, and those that had no ammunition In advised to take axes, in order to make a breast-work of trees for their security at night; and the next day advised them to go forward to the Upper Gap of Swarotawro (Lorberry Junction) and there to make another breastwork of trees, and to stay there two or three days in order to oppose the enemy if they should attempt to come that way; which, if they had done, I am inclined to think what has since happened, would have been prevented.

“I promised them to go to Tulpehocken, and provide powder and lead, and a sufficient quantity of lead to be sent immediately after them. But they went no further than to the top of the mountain, and there those that had ammunition, spent most of it in shooting up into the air, and then returned back again after firing all the way, the great terror of all the inhabitants thereabout, and this was the case with almost all the others, being about 500 in different parts of the neighborhood; there was another company who came from the lower part of Bern Township, as far as Mr. Freme’s Manor, so that when I came to Tulpehocken I found the people there more alarmed than they were near the mountain. For when they saw me come along they were overjoyed, having heard that we were all destroyed, and that the enemy were just at their backs, ready to destroy them. At Tulpehocken there was no lead to be had; all that could be heard from Reading was taken to Paxtang. I therefore sent an express over to Lancaster to Mr. Shippen that evening, Desiring him to send me some lead. He sent me seven pounds, being all that town people were willing to part with, as they themselves were under great apprehensions. I also procured twenty pounds of powder, papered up in one quarter pounds, and ordered out a quantity of bread near the mountains, but when I returned home I learned that my people had given over the pursuit in the manner above mentioned. I have since distributed a good deal of the powder and lead and the bread I ordered to the poor people who are removing from their settlements on the other side of the mountain (Pine Grove Township) from whence the people have been removing all this week.

“It is impossible to describe the confusion and distress of those unhappy people. Our roads are continually full of travelers. Those on the other side, of the men, women and children, most of them, barefooted, have been obliged to cross those terrible mountains with what little they could bring with them in so long a journey through ways almost impassable, to get to the inhabitants on this side. While those who live on this side near the mountain are removing their effects to Tulpehocken. Those at Tulpehocken are removing to Reading, and many at Reading are moving nearer to Philadelphia, and some of them quite to Philadelphia. This is the present unhappy situation of Pennsylvania.”

The letter from Mr. Parsons to Secretary peters conveyed the first news of the massacres in Pine Grove Township to the provincial council at Philadelphia. Reference is made to the killing of Henry Hartman, and the finding of two other men, who had been killed and scalped.

Mr. Parsons wrote:

“Yesterday afternoon I was informed that Adam Read was coming over the mountain and reported that he had been at the house of Henry Hartman (a resident of Pine Grove Township), whom he saw lying dead, having his head scalped. I sent for him, and before five o’clock this morning he came to me and told me that between eleven and twelve o’clock yesterday being then at his home on his plantation on the west side of ‘Swatawro,’ about nine miles from my house and about five miles from the nearest settlement on this side the hills, he heard three guns fired toward Henry Hartman‘s plantation which made him suspect that something more than ordinary was the occasion of that firing. Whereupon he took his gun and went to Hartman’s house being about a quarter of a mile from his own, where he found Hartman lying dead with his face to the ground, and all the skin scalped, from his head. He did not stay to examine in what manner he was killed, but made the best of his way through the woods to this side of the mountain. He told me further that he had made oath before Adam Reed, Esquire, of the whole matter. This day I set out with some of my neighbors to go and view the place and to see the certainty of the matter and to assist in burying the dead body.

“Mr. Reed had appointed the people about him to go with him for that purpose, and we intended to meet him at the place by way of Shamokin Road. When we got to the top of the mountain we met with seven or eight men who told us they had been about two or three miles further along the road and had discovered two dead men lying near the road about two hundred yards from each other and that both were scalped, whereupon I advised to go to the place where these two men were, and with great difficulty we prevailed with the others to go back with us then being then twenty-six men strong. When we came to the place, I saw both the men lying dead and all the skin of their heads was scalped off. One of them we perceived had been shot through the leg. We did not examine further, but got some tools from a settlement that was just by and dug a grave and buried them both together in their clothes just as we had found them to prevent their being torn to pieces and devoured by wild beasts. There were four or five persons, women and children yet missing. one of the dead men had been over this side of the mountain with his family and was returning with his daughter to fetch some of their effects that were left behind. She is missing for one. It is not for me to describe the horror and confusion of the people here and of the country in general. You can best imagine that in your own mind.”

In a letter to the Pennsylvania Gazette on November 3, 1775, reference is also made to the finding of two murdered men “along Shamokin Road.” The bodies were found “near the first branch of the Swatara on the road to Shamokin. One of the men was John Odwaller, who had a plantation in, what is now the upper part of the borough of Pine Grove. Odwaller and his family had removed some of their effects to the south side of the mountain, and he and his eleven-year-old daughter were returning, with other persons to carry away some of the things that remained.

They were approaching the ford near where the Little Swatara flows into the Swatara, along what is now the Fredericksburg Road south of Pine Grove Borough when they were set upon by Indians. Odwaller was killed outright, and his daughter was carried away. One other man, whose name was unknown was killed and several women were also carried away.

Almost simultaneous with the murder of Henry Hartman, the news of the massacre of the Eberhart family was brought to the settlers. George Eberhart, and his family, had come to this country from Germany on the ship, Jacob, on October 2, 1749, and had built a home near the southerly part of Pine Grove Borough, just west of St. Peter’s Church. When the Indians made their descent on the township they launched a surprise attack on his cabin. Eberhart was slain and scalped, together with his wife and all their children except Margaret Eberhart, a child of six years of age, who witnessed the brutal murder, and the burning of her home. She was taken captive by the Indians and carried to Kittanny. From there she was taken to an Indian camp along the Muskingum in Ohio. For more than nine years, she was compelled to live after the modes of the Indians.

In 1763, Colonel Bouquet made his campaign against the Indians on the Ohio, and in the following year conquered them and compelled them to sue for peace. One of the conditions upon which peace was granted was that the Indians should deliver up all the women and children whom they had taken into captivity. Among them were many who had been seized when very young and had grown up to womanhood in the wigwam of the savage. They had contracted the wild habits of their captors, learned their language and forgotten their own, and were bound to them by ties of the strongest affection. Margaret was delivered with other captives to Fort Pitt. From there a great number of the restored prisoners were brought to Carlisle. Col. Bouquet advertised the names and descriptions of captives, and friends of Margaret went to Carlisle and brought her back to the Tulpehocken settlement, where she was married, on February 8, 1771, to John Sallada, and became the ancestress of a large posterity.

About the time of the Eberhart massacre Jacob Gistwite was killed in the neighborhood of Suedburg. The unfortunate victim had settled there the previous spring and was erecting a log cabin at the time of his murder. He was found by relief parties lying near the unfinished cabin with the skin all scalped from his head.

Coincident with the murders near the Swatara was that of Michael Ney, who lived on a clearing on the northerly side of the Blue Mountain south of Hammond Station. Two of the Ney boys were at work in a clump of woods near their clearing loading wood on a wagon when they were set upon by several Indians, who sprung from the bushes and attacked the boys. Michael Ney knocked one of the Indians to the ground and defended himself with a piece of wood against his other assailants. The Indian who was grappling with his brother, struck him a stunning blow, on the head, and then assailed Michael, by hitting him on the head with his tomahawk. He was struck other blows and died almost instantly of his injuries. The other brother became conscious, but witnessing the murder of his brother feigned death. After Michael had been killed, the Indians, believing the other brother dead ran away. As soon as the Indians had departed, the surviving brother ran home and informed his parents of the melancholy news. The neighborhood was alarmed and some of the farmers set out in pursuit of the Indians, who succeeded in making their escape.

The effect of the murders upon the other residents of Pine Grove Township beggared description. Most of the settlers were poor, and many almost impoverished. Forced by a hostile foe to flee, they abandoned their homes in the greatest confusion, bringing with them whatever small effects they could carry. For several days the almost impassable roads across the mountains witnessed the moving of numbers of families to seek refuge among charitable neighbors on the south side.

In a letter to Governor Morris, on November 2d, Col. Weiser describes the wretched condition of the settlements in Pine Grove Township during this exciting period. His letter also indicates, with some sarcasm the want of patriotic feeling on the part of the residents south of the mountain despite their perilous situation.

He wrote:

“I am going out early tomorrow morning with a company of men, how many I can’t tell as yet, to bring away the few and distressed families on the north side of Kittinany Hills (Pine Grove Township) tet alive (if there is yet alive such). They cry loud for assistance, and I shall give as my opinion tomorrow, in public meetings of the townships of Heidelberg and Tulpehocken, that they few who are alive and remaining there (the most part is come away) shall be forewarned to come to the south side of the hills, and we will convey them to this side. If I don’t go over the hills myself, I will see the men so far as the hills and give such advice as I am able to do. There can be no force. We are continually alarmed; and last night I received the account of Andrew Montour. My son Peter Weiser came up this morning from Reading, at the head of about fifteen men, in order to accompany me over the hills. I shall let him go with the rest; had we but good regulations, with God’s help we could stand at our places of abode, but if the people fail (which I am afraid they will, because some go, some won’t, some mock, some plead religion and a great number are cowards). I shall think of mine and my family’s preservation and quit my place, if I can get none to stand by me to defend my house.”

Two years after the murders in Pine Grove Township and on the south side of the mountain where Fort Henry was later constructed, the colonial secretary requested Peter Spycker, of Tulpehocken to compile a list of the people murdered or taken captive.

In a letter to the secretary, dated November 28, 1757, he wrote:

Honored Sir:

According to your desire, to make out a list of the people who are murdered and taken captive by the Indians, I send hereby so near as possible, I could get, to wit-

George Eberhard and his wife and 5 children killed and scalped. Balzer Shefer killed and scalped and his daughter taken captivity (in the Month of October (31st) 1755, on the Shoemokee Road over the Kittitiny Hill.

Henry Hartman killed and scalped in his house over the Mountain (in November 1755).

John Leyenberger and Rudolf Kendel, George Wolf and John Apple, Caspar Spring and Jacob Ritzman, Fred Wieland and George Martin Bouer are all killed (in November 1755 as they were going on the watch on the Kittiting Hill on Saturday at noon where Fort Henry is built at present).

Philip House killed the same evening in his house.

Henry Robels, wife and 5 children and a girl of William Stein are killed and some scalped (on the next day or Sunday).

_______________________________________