The Genealogical and Biographical Annals of Northumberland County Pennsylvania was published in 1911 by J. L. Floyd Company of Chicago. According to the sub-title, it contained “a genealogical record of families including many of the early settlers, and biographical sketches of prominent citizens prepared from data obtained from original sources of information.” The book is available as a free download from the Internet Archive.

One of the biographical sketches was on Shikellimy [Shikellamy], an Indian prominent in the Central Susquehanna River area of Colonial Pennsylvania, a colleague and friend of early European settler Conrad Weiser, and a regular attendee at councils in Philadelphia. Shikellamy also had connections to the Six Nations, who had given him the authority to handle their affairs in the colony.

The biographical sketch is sympathetic to Shikellamy. It looks at the power he was believed to have as compared with the power he actually had. It tries to reconstruct his genealogy. In his last days, he was at the mercy of friends and the colonial government for sustenance.

Cautionary Note: Some language used in describing Indians [e. g., “savages”] is found withing the biography.

_________________________________________________

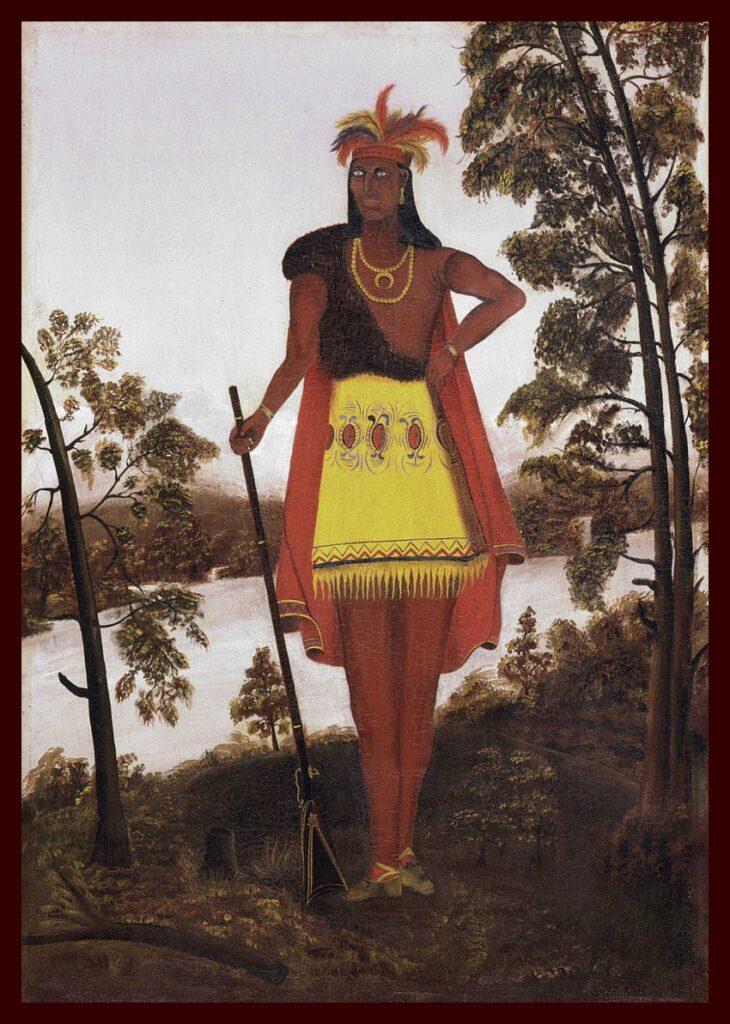

SHIKELLAMY (or SHIKELLIMY)

Shikellamy, the Indian chief whose name for a score of years was associated with every important transaction affecting the Indians of the Susquehanna Valley, was a Susquehannock by birth, descending from the ancient Andastes, and thus returned to govern the land from which his fathers had been expelled. Like many of the more enterprising youth of his tribe, he had entered the military service of their conquerors; his valor in war was rewarded by adoption into the Oneida tribe, of which he at length became a chief, an exceptional preferment for one not a member of that nation by birth.

The Iroquois, although not the actual occupants of any part of Pennsylvania, played an important part in its history, throughout the Colonial and Revolutionary periods. They inhabited the fertile region south of Lake Ontario, and about the headwaters of the Hudson, the Delaware, the Susquehanna, and the Allegheny Rivers, including the valley of the Mohawk on the east and that of the Genesee on the west. Five tribes, the Senecas, Onondagas, Oneidas, Cayugas and Mohawks, originally constituted the confederacy, whence they were called the Five Nations; a sixth, the Tuscaroras, was admitted about the year 1712, and after that they were known as the Six Nations. Each tribe exercised exclusive jurisdiction in purely domestic affairs, while matters concerning the nation as a whole were determined by the great council at Onondaga. This was the center of their power, which was practically co-extensive with the thirteen original States, embracing also southern Canada and a part of the Mississippi Valley. In the extent of their dominion, their absolute power, and the statecraft exercised in rendering conquered tribes subsidiary to their purpose, they have been not inaptly styled “the Romans of America.” In all the arts of a savage people they excelled. Their fields were well cultivated, their towns were strongly fortified, their form of government secured practical unanimity in the execution of military projects, and in their intercourse with Europeans their chiefs often evinced a remarkable skillfulness in diplomacy and profoundness of policy. Their career of conquest was doubtless inaugurated by the subjugation of the immediately contiguous tribes and thus, in the extension of their power to the south, the Andastes and Lenni Lenape were first brought under their sway. The Shawanese, Genawese, Conoys and other Pennsylvania tribes also acknowledged their supremacy, and for the better government of these troublesome feudatories the great Onondaga council was constrained, in the early part of the eighteenth century, to place over them a resident viceroy. To this responsible position Shikellamy was appointed. It is not probable he was appointed viceroy before 1728; he was not present at the treaty with the Five Nations at Philadelphia in July of the preceding year, and LeTort does not mention him among the Indians of consequence whom he met “on the upper parts of the river Susquehanna” in the winter of 1727-1728. The first conference that he attended at Philadelphia was that of July 4-5, 1728, but it does not appear that he took any active part in the proceedings. He was present on a similar occasion in the following October, when, after the close of the conference, the Council considered “what present might be proper to be made” to Shikellamy, “”of the Five Nations, appointed to reside among the Shawanese, whose services had been and may yet further be of great services had been and may yet be further be of great advantage to this government.” The secretary of Council had gained a more accurate idea of his functions three years later, when, in the minutes of August 12, 1731, he gives his name and title as “Shikellamy, sent by the Five Nations to preside over the Shawanese.” At the close of the conference which began at Philadelphia on that date, the governor having represented that he was “a trusty good man and a great lover of the English.” he was commissioned as the bearer of a present to the Six Nations and a message inviting them to visit Philadelphia. This they accordingly did, arriving August 18, 1732. Shikellamy was present on this occasion, when it was mutually agreed that he and Conrad Weiser should be employed in any business that might be necessary between the high contracting parties. In August, 1740, he came to Philadelphia to inquire against whom the English were making preparations for war, rumors of which had reached the great council at Onondaga. He was also present at the conference at Philadelphia in July, 1742, at the treaty at Lancaster in June and July, 1944, and at the Philadelphia conference of the following August. He does appear to have taken a very active part in the discussions, a privilege which, among the Six Nations, seems to have been reserved for the Onondagas. In April 1748, accompanied by his son and Conrad Weiser, he visited Philadelphia, but no public business or importance was considered.

Shikellamy’s residence is first definitely located in 1729 in a letter of Governor Gordon to “Shekellany and Kalaryonyacha at Shamokin [Sunbury].” Within the next eight years he had removed some miles up the valley of the West Branch. In the journal of his journey to Onondaga in 1737 Conrad Weiser states that he crossed the North Branch from Shamokin on the 6th of March; on the 7th he crossed Chillisquaque Creek, and on the 8th he reached the village where Shikellimy lives. “On the 8th he reached the village where Shikelimo lives, who was appointed to be my companion and guide on the journey. He was, however, far from home on a hunt. Weather became bad and the waters high, and no Indian could be induced to seek Shikelimo until the 12th, when two young Indians agreed to go out in search of him. On the 16th they returned with word that Shikelimo would be back next day, which so happened. The Indians were out of provisions at this place. I saw a new blanket given for about one third of a bushel of Indian corn.”

The site of this village is beyond doubt on the farm of Hon. George F. Miller (1886), at the mouth of Sinking Run, or Shikellamy’s Run, at the old ferry a half mile below Milton, on the Union County side. Bishop Spangenberg and his party passed over the same route June 7, 1745; after passing Chillisquaque Creek, and the “site of the town that formerly stood there,” they “next came to the place where Shikellamy formerly lived,” which was then deserted; the next point noted is Warrior’s Camp (Warrior Run). Spangenberg certainly did not cross the West Branch; if Weiser had done so in 1737 there is every reason to suppose that he would have mentioned it, which he does not; from which, it there were no other data bearing on this subject, it would be fair to conclude that in 1737 Shikellamy resided on the east bank of the West Branch at some point between Chillisquaque Creek and Warrior Run. But there are other data, When the land office was open for “the new purchase,” April 3, 1769, there were very many applications made for this location. in all of them it is called wither old Muncy town or Shikelliamy’s town. It is referred to as a locality in hundreds of applications for land in Buffalo Valley.

Shikellamy, some time after Weiser’s visit, between1737 and 1743, removed to Shamokin (now Sunbury) as a more convenient point for intercourse with the proprietary governors. There he resided the remainder of his life. from this point he made frequentl journeys to Onondaga, Philadelphia, Tulpehocken, Bethlehem, Paxtang and Lancaster, as the discharge of his important public functions required. On October 9, 1747, Conrad Weiser says that he was at Shamokin and that Shikellamy was very sick with fever. “He was hardly able to stretch forth his hand. His wife, three sons, one daughter and two or three grandchildren were all bad with the fever. There were three buried out of the family a few days before, one of them was Cajadis, who had been married to his daughter above fifteen years, and was reckoned the best hunter among all the Indians.” He recovered, however, from this sickness, and in March, 1748, was with Weiser, at Tulpehocken, with his eldest son, “Tagheneghdourus,” who succeeded him as chief and representative of the Six Natons. He died in April, 1749, at Sunbury.

Loskiel thus notices this celebrated inhabitant of the valley: “Being head chief of the Iroquois living on the banks of the Susquehanna as far as Syracuse, New York, he thought it incumbent upon him to be very circumspect in his dealings with the white people. He mistrusted the Brethren (Moravians) at first, but upon discovering their sincerity became their firm and real friend. He learned the art of concealing his sentiments; and, therefore, never contradicted those who endeavored to prejudice his mind against the missionaries. In the last years of his life he became less reserved, and received those Brethren that came to Shamokin. He defended them against the insults of drunken Indians, being himself never addicted to drinking. He build his house upon pillars for safety, in which he always shut himself up when any drunken frolic was going on in the village. In this house Bishop Johannes Von Watteville, and his company, visited and preached the Gospel to him. He listened with great attention, and at last, with tears, respected the doctrine of Jesus, and received it with faith.”

There is ample evidence in contemporary records that Shikellamy’s position was one of responsibility and honor rather than profit or emolument. In the general system of national polity of which the Iroquois Confederacy was the only type among the aborigines of America, his post corresponded to that of a Roman proconsul. But there the parallel ceases. Although he was charged with the surveillance of the entire Indian population of central Pennsylvania, and doubtless exacted a nominal tribute, no provision whatever was made for his personal necessities, to which, with characteristic diplomacy, the Provincial authorities were induced to contribute. “The president likewise acquainting the board, that the Indians, at a meeting with the Proprietor and him, had taken notice that Conrad Weiser and Shikellamy were, by the treaty of 1732, appointed as fit and proper persons to go between the Six Nations and this government and to be employed in all transactions with one another, whose bodies, the Indians said, were to be equally divided between them and us, we to have one half and they the other; that they had found Conrad faithful and honest; that he is a true, good man, and had spoken their words and out words, and not his own; and the Indians having presented him with a dressed skin, to make him shoes, and two deer skins, to keep him warm, they said, as they had thus taken care of our friend, they must recommend theirs (Shikellamy) to our notice; and the board, judging it necessary that a particular notice should be taken of him accordingly, it is ordered that six pounds be laid out for him in such things as he may most want.” He was expected to hunt and fish, the natural modes of subsistence with an Indian, regardless of his station, but in the waning vigor of old age he was obliged to relinquish the chase, and in October, 1747, Weiser found him a condition of utter destitution. This he describes as follows, in a letter to Council: “I must at the conclusion of this recommend Shikellamy as a proper object of charity. He is extremely poor; in his sickness the horses have eaten all his corn; his clothes he gave to Indian doctors to cure him and his family, but all in vain; he has nobody to hunt for him, and I can not see how the poor old man can live. he has been a true servant to the government and may perhaps still be, if he lives to do well again. As the winter is coming on I think it would not be amiss to send him a few blankets or match-coats and a little powder to do it and you could sent it up soon. I would send my sons with it to Shamokin before the cold weather comes.”

Upon the consideration of this letter it was immediately decided by Council that goods to the value of sixteen pounds should be procured and forwarded to Shikellamy by Conrad Weiser. The consignment included five stroud match-coats, one fourth of a cask of gunpowder, fifty pounds of bar lead, fifteen yards of blue “half-thicks,” one dozen best buck-handled knives, and four duffel match-coats.

On the occasion referred to (October 1747) Shikellamy was quite ill. Before Weiser left Shikellamy was able to walk about “with a stick in his hand.” The following March he was so far recovered as to visit Tulpehocken, and in April, 1748, he was at Philadelphia. After this he seems to have had a relapse, for on the 18th of June in the same year the Provincial Council was informed that he was “sick and like to lose his eyesight.” He again recovered, however, and in the following December, made a visit to Bethlehem. On the return trip be became ill, but reached his home with the assistance of Brother David Zeisberger, who attended him during his sickness and administered the consolations of religion. His daughter and Zeisberger were present when he died. The latter, assisted by Henry Fry, made a coffin, in which, with the possessions he had valued most highly during life, the mortal remains of the great viceroy were interred at the burial ground of his people.

At his first appearance in Colonial affairs, Shikellamy had a son and daughter and probably other children. A present was provided for his wife and daughter at the conclusion of the treaty of October, 1728; and on August 18, 1729, the governor sent him a message of condolence upon the death of his son and a shroud with which to cover him. Another son, Unhappy Jake, was killed by the Catawbas, with whom the Six Nations were at war, in 1743, and in a letter dated January 2, 1744, Weiser informs Secretary Peters of the fact, suggesting also the propriety of sending the bereaved father “a small present, in order to wipe off his tears and comfort his heart.” Several days before Weiser’s arrival at Shamokin, November 9, 1747, there were three deaths in the family, Cajadies, his son-in-law, the wife of his eldest son, and a grandchild. It is evident that he had more than one daughter at that time; “his three sons” are also mentioned. The eldest, Tachnechdorus, succeeded to the former authority of his father, and, with two others, “sachems or chiefs of the Indian nation called the Shamokin Indians,” affixed his signature to the Indian deed of 1749, Conrad Weiser, writing to Governor Morris under date of March 1, 1755, styles him “Tachnechdorus, the chief of Shamokin, of the Cayuga nation,” the latter part of which is difficult to harmonize with the fact that his father is uniformly referred to as an Oneida. His brother seems to have been associated with him: Richard Peters, the Provincial secretary, in his account of the eviction of settlers from lands north of the Kittatinny mountains not purchased from the Indians, states that his party was accompanied by three Indians from Shamokin, “two of which were sons of the late Shikellamy, who transact the business of the Six Nations with this government.” Tachnechdorus was also known to the English by the name of John Shilellamy. In 1753 he had a hunting lodge at the mouth of Warrior run and resided at a small Shawanese town below Muncy Creek on the West Branch. These facts are derived from Mack’s journal, which also states that Shikellamy’s family had left Shamokin, where they found it very difficult to live owing to the constant drafts upon their hospitality. In April, 1756, he was at McKee’s fort, but greatly dissatisfied, as nearly all his party were sick.

Sayughtowa [James Logan], a younger brother of Tachnechdorus, was the most celebrated of Shikellamy’s sons. he lived at the mouth of the Chillisquaque Creek August 26, 1753, and in 1765 in Raccoon Valley. “In 1768 and 1768 he resided near Reedsville in Mifflin County, and has given his name to the spring near that place, to Logan’s branch of Spring Creek, in Centre County, Logan’s path, etc.

In 1774 occurred Lord Dunmore’s expedition against the Shawanese towns, now Point Pleasant, West Virginia, which was the occasion of Logan’s celebrated speech, commencing “I appeal to any white man to say if he ever entered Logan’s cabin hungry and he gave him not meat,” which will go down to all time, whether properly or not, as a splendid outburst of Indian eloquence.

“He could not speak tolerable English, was a remarkably tall man — over six feet high — and well proportioned of brave, open and many countenance, as straight as an arrow, and apparently afraid of no one.” Heckewelder, who thought him a man of superior talents, called on him in April, 1773, at his settlement on the Ohio below Big Beaver; the same writer says he afterward became addicted to drinking, and states that he was murdered in October, 1781, between his residence and Detroit. He was sitting with his blanket over his head, before a camp fire, his elbows resting on his knees, when an Indian who had taken some offense stole behind him and buried his tomahawk in his brains. His English name, James Logan, was conferred in honor of the distinguished Friend who was so long and prominently identified with Colonial affairs in Pennsylvania; he is generally known to history as “Logan, the Mingo.”

________________________________________

The original painting at the top of this post is part of the collection of the Philadelphia Museum of Art, but the digital image shown here is from Wikipedia and is in the public domain.

Corrections and additional information should be added as comments to this post.

[Indians]