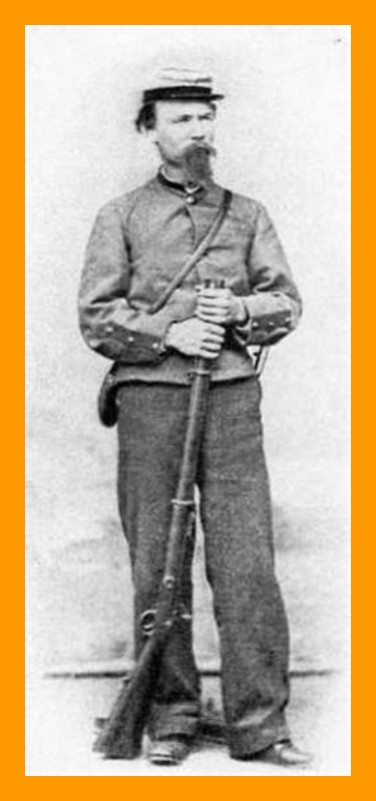

A portrait of Confederate Sergeant. Barry Benson, who tunneled out of Elmira Prison, Elmira, New York.

Benson, of Company H., 1st South Carolina Infantry was a prisoner at Elmira from July 25, 1864 to October 7, 1864. He had arrived at Elmira Prison via the Erie Railroad from Jersey City, New Jersey, ten days after the train wreck at Shohola, Pike County, Pennsylvania, and was in one of the early groups of prisoners to arrive at the Union prison.

At 4:00 a.m. on October 7, 1864, he and nine companions entered a tunnel sixty-five feet long, which they had been digging for about sixty days. Two of the ten headed north to the area around Auburn, New York, but eight headed south – including Barry Benson. Those who traveled south did so alone. Different routes were taken.

Several of the escapees wrote detailed stories of their escape, and these are reprinted in the book, The Elmira Prison Camp, a copy of which is available as a free download from the Internet Archive (click on title and follow download instructions at left). The portrait of Barry Benson, in uniform, is also from the same book (see top of post).

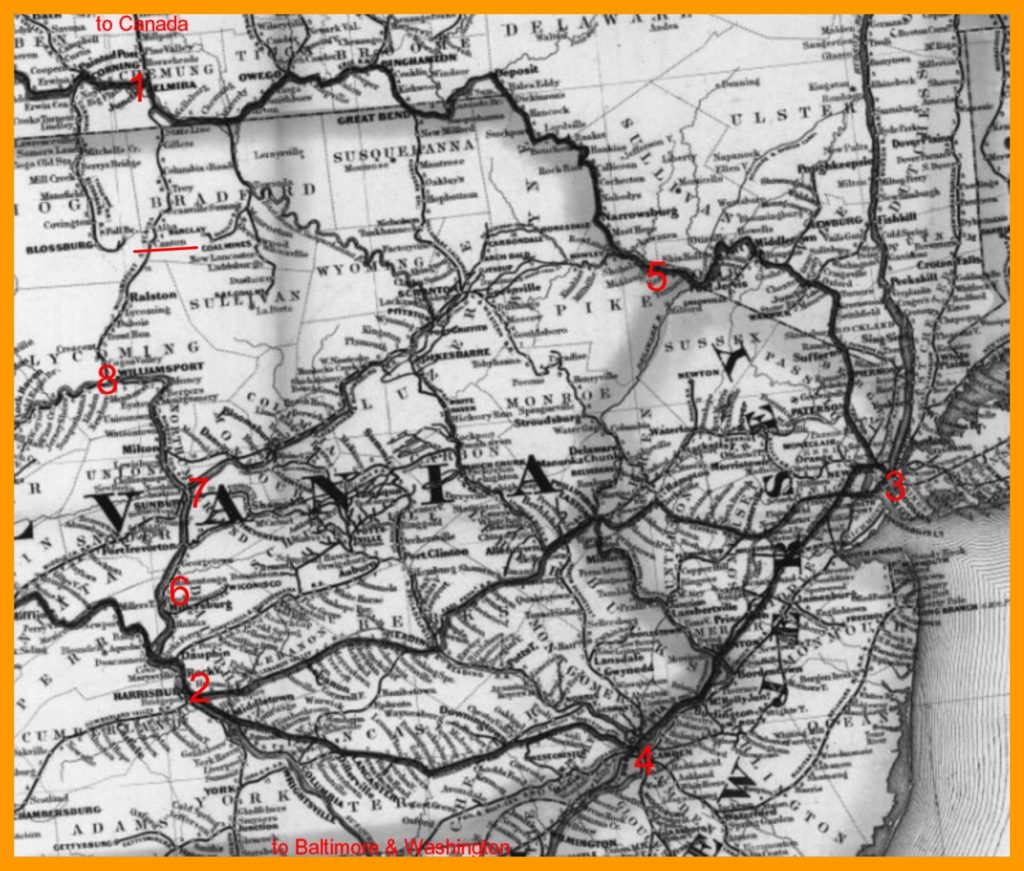

The Escape Route of Barry Benson. On the map above, the Elmira Prison Camp is designated as #1. Following south on the Northern Central Railroad, the town of Canton is underlined in red. South from Canton is Williamsport (#8), Northumberland and Sunbury (#7), Millersburg (#6), and Harrisburg (#2).

Portions of his detailed escape account are presented below as they pertain to the Northern Central Railroad from Canton in Bradford County, Pennsylvania, to Baltimore. The entire account can be found in The Elmira Prison Camp, written by Clay W. Holmes in 1912.

After crossing into Pennsylvania, Barry Benson came upon the village of Fall Brook on 10 October 1864. It was there he took a meal with a man named Michael Adams – the first cooked meal since his escape from prison. From the time of his escape, he had lived on apples. According to Wikipedia, Fall Brook is a now a ghost town in Tioga County, Pennsylvania, and has been deserted since 1900 when the coal ran out. Adams told Benson that Canton was about nine miles to the south, so he headed off in that direction.

At a cottage a short distance from the Adams house, Benson

stopped… to make a survey. All seemed asleep. The front door being locked, I went to the back door. It was locked too. On the banisters hung trousers and stockings. As I had no stockings I put on a pair; and as I had no drawers, I put on a pair of trousers under mine….

It was nine miles to Canton. It was a rough way, up mountains, down into valleys. I saw the moon set behind me, then rise and set again…. I walked all night, stopping but twice, once to borrow a chicken, and once to examine a horse in a pasture….

And at daylight I struck the railroad three miles north of Canton. By what devious route I wandered this Monday night’s march, I never will know….

In a field just west of the road, in a hollow or wide gully, overgrown thick with bushes, I camped. I ate a broiled chicken, regretting now I had not taken two, and slept through the Tuesday.

At dark I marched, passing by Canton and its little old church steeple pointing the way to heaven.

Five miles south from Canton I came to a track-walker’s shanty just at the right of the road. A sleeper snored inside. A barrel of potatoes stood at the door. When a man has lived at a hotel in Elmira from July to October he realizes that roasted potatoes go well with broiled chicken, so I helped myself to potatoes, thank you.

In a square hole cut in the wall for a window, was something dark. I felt of it. It was rough cloth. I pulled it gently…. I unhooked to buttonholes from two nails in the wall and drew the coat out.

It was a famous good overcoat, thick and warm, albeit shabby, as it suited my other dress.

Stockings, breeches, overcoat! What good thing next? ….

A mile-post told me it was 33 miles to Williamsport….

This was a beautiful country. I knew it even by moonlight, and I longed to see it by day. On the right, far below, lay a valley, through which ran a stream, and along its course lay farms dotted with farmhouses. Beyond the valley slept mountains dark and wooded.

On my left hand looked down a mountain, dark with shadows, and at one place a cascade came tumbling down its side, white in the moonray, so sweet the music of its singing in the silence of the midnight. Now, indeed, truly….

The next day, after spending the night camping near the railroad, Benson encountered a train of box cars filled with soldiers, to whom he waved, and as they yelled to him, he pointed south and shouted back, “On to Richmond!” He then mused over the idea of enlisting and going down to Richmond as a recruit, and then deserting – of course keeping the thousand dollar bounty. This idea was quickly dismissed.

On 12 October Benson continued toward Williamsport.

It was good daylight when I reached the depot at Williamsport…. Evidently the soldiers of the day before had stopped here awhile. Pieces of broken hardtack strewed the ground. Some were as big as a dollar…

If the people of Williamsport had known who I was, and that I was there, I felt sure they would come out to see me, but as they did not know, and as I had not time to tarry, I passed on.

I walked over the bridge; then the railroad ran on an embankment through wide fields planted in corn, turnips, and pumpkins. I took a turnip as a sample; the pumpkins were too huge to take…. As I followed the road up Bald Eagle, I picked up chestnuts in the ruts….

Hid between two great boulders, I lay down and slept till late in the evening…. Then… I went down to the railroad…

The railroad now followed close to the bank of the Susquehanna, and the foot of Bald Eagle Mountain – there being but a narrow strip, and the foot of Bald Eagle Mountain – there being but a narrow strip; often the railroad was cut into the mountain itself. The scenery was fine; I knew that in the moonlight. That was pleasant to my eyes, but as for my feet, I suffered. For the soles of my shoes were worn through, wide holes let my bare feet upon the ground. Not so unpleasant if the road were smooth, but, here, for miles, the road was ballasted with broken rock and I must carefully keep step with the ties. Walking on crossties is tiresome, as well as monotonous, and after a little of it I was fain to walk again upon the broken rock, and that hurt my feet.

The river being hard by, it came to me I might find a boat and so escape walking…. and there was a boat, chained to a stump. There was no lock. I took up the oars and pulled out to midstream….

Some miles I rowed, and drifted – the river running eastward, passing a big hotel on the left bank, advertising itself in a gigantic sigh I could read far out in the stream. At length came to my ears the ominous sound of falling water, and I was soon aware of a fall below. I stayed in the boat as long as I dared, then I landed on the right bank again.

Here was a lumber yard, and, as I soon found, a distillery, all in one enclosure…

Benson then found a business coat, better than any one he had.

Traveling the railway again, in a few miles I came to a place where I heard music and dancing. Near the depot was a large house, lit up – a hotel, I though – and there was the ball I waited, charmed with the music and the rhythm of the feet….

Under that depot I found a valise…. Some fellow, coming to the ball on foot, had worn his old clothes; arriving had changed, and this valise, hidden there, now held his old clothes. Did I want the? Of course….

Some time in the night I crossed the river on the railway bridge, to the eastern side, passing soon after through a deep cut. When day came, I did not stop, as usual, but marched and rested and slept, at intervals.

Then he arrived at Northumberland, just north of Sunbury, and knocked at the door of a house.

Emboldened by my day’s safety, I turned into the town.

A young woman answered and after he asked for a drink, she gave him some supper consisting of home-baked bread spread thick with butter.

I thanked her and went ruefully away, vowing that whenever the war should end I would come back to Northumberland.

I went back to the railroad; a train of lumber had come it, the engine smoking. I had never beaten my way on a train; was I too old to begin? Under the projecting ends of boards I stowed myself. The train moved off, and I was happy. Soon it stopped, and I waited for it to go on. I waited half an hour. Then, crawling out, I found the engine gone. My ride was three short miles to Sunbury….

Coming back to the station, I found many people there waiting for a train. I mixed with them. … A whistle blew, and the express train shot up to the station and stopped…. Everybody was getting off, and everybody was getting on….

Off shot the train, and Benson on it….

I stay on the platform, watching though the glass for the conductor to come, collecting fares. He is slow, the slower the better…. At length he comes. I watch till he is nearly at the door. Then I go down, place my left foot on the end of the bottom step, grasp the rail with my left hand, and swing my body forward, flat against the car…. I swing my body back, and sit on the steps.

Presently, back comes the conductor. I sit still. He comes behind me and stops. I know he sees me…. I know he is holding his lamp over me, looking at me. I sit still. I am wondering what he will say….

He says nothing. He goes away.

And so I sit for two hours….

It was on this two hour stretch of the railroad, sitting on the step of the platform, that Barry Benson passed through the Lykens Valley – through the stations at Herndon, Dalmatia, Millersburg, Dauphin Borough, and eventually arriving at Harrisburg.

Now we are in Harrisburg. Everyone comes out, and I learn that we change cars here. It is now twelve o’clock. At one, a train leaves for Baltimore. I wait in the waiting-room with the others….

Now, again, I am on the platform of a car….

I watch through the glass. The conductor comes through the car. Again I am hanging outside.

Then – a touch on my arm! I face the conductor.

Benson is asked for a ticket and explains he doesn’t have one and has no money, but is going to York to see his sister who is not expected to live long. The sympathetic conductor tells him to go into the car and have a seat, as it was less dangerous inside. Finally, the train arrives at York.

People are getting off. I sit still, loath to go. Then I reflect, if the conductor finds me on the car again, after the facts I have told him about my dear sister, he will be suspicious, and he will hand me over to the police…. I get off quickly.

For the next forty-two miles, Barry Benson walked, crossing the Mason-Dixon line and arriving at Cockeysville – only fifteen miles from Baltimore. Then a train came along and stopped for water. Benson climbed aboard. It was a freight train and he was confronted by the conductor.

“Where are you going?”

“Just to Baltimore.”

“We’re not allowed to let anybody ride on freight; I don’t want to get in any trouble; when we slow up you jump off, you hear?”

“All right, sir!“

By eleven o’clock in the morning Barry Benson arrived in Baltimore.

____________________________________________

This post was first published on the Civil War Blog on May 27, 2014.

Corrections and additional information should be added as comments to this post.