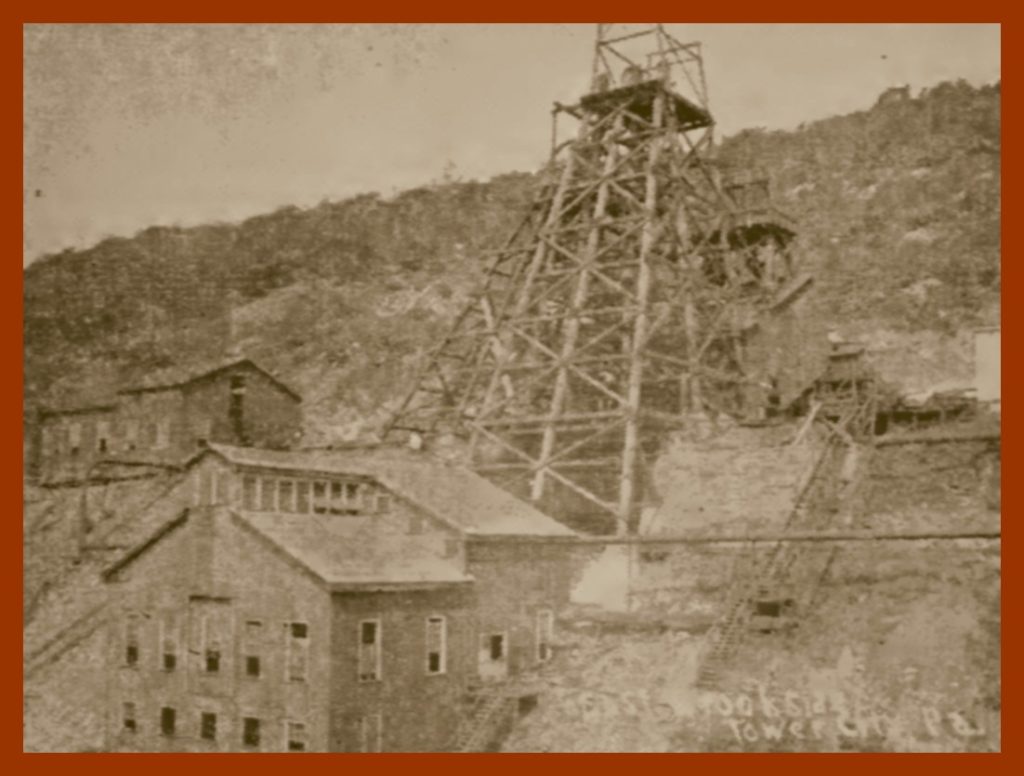

An undated photo post card view of the East Brookside coal mine shaft in Porter Township, Schuylkill County, Pennsylvania. In March 1977, at the time miners were trapped and killed at the same mine which was then operated by the Kocher Coal Company, the West Schuylkill Herald of Tower City reflected on a mine disaster that occurred in August 1913 in which twenty men were killed. The article appeared in the Herald on March 24, 1977.

___________________________________

RECALL MINE DISASTER OF 1913

The recent mine disaster at the Kocher Coal Mine was first time news for the younger generation of this area, also for the many people throughout the country who learned of it through the news media and sympathized with the local residents. However, the senior citizens of our valley were not so prone to disbelief, as their experiences in growing up included hearing reports of mine explosions, rushes of water, no air, and something called black damp.

Back in August 8, 1913, the West Schuylkill Herald, Tower City, carried a full page report of a disastrous explosion at the East Brookside Mine which killed 19 men and injured one, who also later died. We, perhaps, felt during the past few weeks that the news media had imposed on the privacy of the victims and were looking for a sensational story, but the account back in 1913 also gave all the sordid details.

The explosion occurred on Saturday morning, August 2, and the newspaper stated it “made a record for this valley that probably will never be forgotten.

Out of the 19 dead, 10 were Americans, one an Austrian, and eight Italians. The account stated, “Every one of the ten was widely known and respected, and nine were married and leave families.

Quote: “Not only was there sympathy in this valley, but the whole United States sympathizes with us in our affliction.”

“The Austrian was a resident of Reinerton, resided in this community for many years and was thoroughly Americanized, and was a good citizen.” He was Alex Lishmet, 37, a repairmen, who when he died, left a wife and several children.

The eight Italians had come to this country and most of them boarded at Reinerton. Three were married but their names are no longer familiar in this area.

Harry Schoffstall, 29, of Orwin, was the one man who escaped alive, but he died a week later of severe burns. It is said he suffered untold agony, the burns exuding blood and matter. Although it is stated that registered nurses attended him at his home, he was not hospitalized.

The dead were John Lorenz, 60, district superintendent of the Tremont District of the Philadelphia and Reading Colliery, of Tremont, leaving a widow and nine children, mostly grown.

Daniel McGinley, 46, fire boss, left a widow and seven children.

Henry Murphy, 51, fire boss, left a wife and three daughters.

Daniel Farley, 40, left a widow and five children.

John Fessler, 36, left a widow and three children.

Thomas Behney, 29, left a widow and one child.

Jacob Koppenhaver, 27, bottom man, left a widow and four children.

Howard Hand, Muir, 20, was single.

Harry Hand, 24, a brother to Howard Hand, left a widow and three small children.

The story tells of the three caskets of Farrell, McGinley and Murphy, fire bosses, being carried into the Catholic Church for the funeral, all placed in the center aisle. Following the service they were placed in trolleys and hearses and taken to the railroad depot to be loaded on the trains for their places of burial.

The funeral of Behney was held from his home at Reinerton, a double funeral was held tor the Hand boys at “Reiner City,” and the others were held at the homes.

The account of the explosion reads —

The explosion took place in No. 5 level not far from the tender slope and in a tunnel which is being driven from the gangway to make a short cut to the shaft. For the benefit of those who were never inside a mine, we would say that gangway is like the main street of a town, the difference being that it is an underground street or railway and another difference being that it is nearer to hell than to heaven. It varies in width from 8 to 12 feet and in height about the same. It starts at the bottom of a slope or shaft and continues for miles, or only a short distance as the coal holds out. The breasts or working places of the miners start out from a gangway. There a number of gangways in every mine. As a gangway is the main traveling road for the men to and from their work, and as all coal mined must be hauled through a gangway before it is sent to the surface, repairmen are continuously kept on a gangway to see that it is in safe condition and as free from danger as possible. A tunnel differs from a gangway only that it is driven through solid rock or slate to make a shorter cut between two points. It does not follow a vein of coal. A gangway is also used as an airway.

The No. 5 lift at East Brookside was always known to contain gas. The pitch of the vein is about 70 degrees and at places is 16 feet thick. The coal is dry, dusty and very fine. The gangway had to be kept in the best condition to keep the coal from rushing away.

The air in the gangway was very strong and pure and always took care of any gas that might be made or might accumulate at some other point and might be forced into the gangway. That was the condition of the gangway on the day of the explosion. The foreman, assistant foreman, district superintendent, Lorenz, the drivers and laborers of the tunnel used it all morning and there had been no signs of gas.

About 11:20 o’clock there was an explosion in No. 5 lift not far from the tended slope. Charles Heckler, one of the engineers at the water hoist at East Brookside, saw a cloud of dust coming out of the fan hole north of the engine house. Daniel Morgan and his helper, Joe Mendig, who kept the shaft in repair, were at the top of the shaft. They felt a shock. McGinley, Behney, Murphy, Schoffstall and Howard Hand were outside the mine at the top of the tender slope and also felt some shock from the explosion. The six last named at once procured safety lamps and after giving the engineer the signal were lowered into the mine. That was the last seen of them until their bodies were recovered in the mine.

The story then relates and account similar to what took place in the past few weeks [of 1977] – of rescue workers responding, telephone into the mines being used trying to make contact, and many relief workers coming out to help.

A sordidly detailed story tells of the bodies of the men being found, mostly without clothing and shoes, arms and legs hanging only by the skin, many bones broken and crushed to a pulp, bodies and faces burned black. Mining men claimed that this was proof that the explosion took place inside the gangway and the men walked into it. The force of the explosion blew them up against the sides, which accounted for the injuries mostly on the backs.

The bodies of miners were taken to the wash house and cleaned up by teachers, ministers and others who assisted, before being sent to their homes.

Sounding like the recent story: “Mine inspector Price and General Manager Richards are at the colliery night and day and will likely remain there until the bodies of the men are all recovered.”

There was no confusion around the colliery while the rescue parties were in the mine or while the dead were being brought to the surface. Several hundred men, women and children gathered about the works and no one who was called upon to lend assistance, refused to give service. The entrance to the tender slope was roped off and Coal and Iron officials would permit only those who had business there to go behind the ropes. The bodies of the men were carefully covered with canvas, and only those who assisted in washing the bodies, were able to view them before they were sent to their homes.

The first explosion was supposed to have taken place at about 11:20. Whether it was dynamite or gas explosion is not known, although experienced mining men believe it was dynamite. It is known that 175 pounds of dynamite was sent into the mine that morning for the use of the men who are driving a rock tunnel under the direction of contractor Portland of Pottsville.

As near as can be figured out the second explosion took place about 20 minutes before 12 o’clock. The second explosion is believed surely to be caused by mine gas. The theory is that the first shock caused the fall of coal and rock that closed up the gangway beyond the tunnel, preventing the proper circulation of air. The shock also disturbed some hidden gas. The air being diverted by the fall, the gas is supposed to have backed out into the gangway, in so short a time. What is perplexing the officials most, is to find where the gas came from. Another matter that is puzzling is what set off the gas. Did someone walk into it with a naked lamp, strike a match, or open up a safety lamp? Or assuming that the first explosion was from dynamite, did this cause a fire in the tunnel which later set fire to the gas? It is a positive fact that gas will not exploded of its own accord and that fire of some kind is the only thing that will explode it. What set off the gas? Those who could solve the problem are dead.

Other Men in Mine at Time of Explosion

The Herald was informed that in addition to the 20 men injured and killed, there were three other workmen in the mine at the time of the explosion: James Culbert of Reinerton; Frank Farrell, a son of the dead inside foreman; and Hillery Zimmerman of Orwin. They said the first explosion sounded like a heavy door being slammed shut and the second like train of cars passing along the gangway. However, they were at a safe place.

August 15, 1913

The Herald of August 15, 1913 reports that after thorough investigation it was proved that the first explosion at East Brookside was not caused by dynamite. The box of dynamite was found by rescue workers completely intact, just as it had been taken into the mine.

The theory is now that there was only one explosion. It was believed that the first noise was a pillar of coal being released, closing the gangway and loosening up a large body of hidden gas.

The bodies of John Fessler and Daniel Farley had not been found at this time. Work continued night and day to clear the gangway.

In this issue, reporting the obituary of Harry Schoffstall, it was stated that this was the second explosion in which he was involved, the first being on November 27, 1912, when Daniel Tobias of Donaldson lost his life.

[Example from an obituary:] “Henry Winfield Schoffstall was one of the best known young men in the upper end of the valley. He was loved and respected by everyone who knew him and his friends were many. He was a Christina gentleman, not only in church on Sunday but every day in the week. He took an active interest in the Orwin Union Sunday School and was the teacher of the Young Ladies’ Bible Class of the school. As a husband and father he was ideal and his married life was one long honeymoon.”

The four year-old daughter of Henry Schoffstall grew up to later become a music teacher in the Porter Township Schools.

In the August 22, 1913, issue, the bodies of Farley and Fessler were reported being found. An inquest was held. No one was found to blame and the newspaper carried many interview of the men who helped at the mine.

_______________________________________

News article from West Schuylkill Herald, Mach 24, 1977, via Newspapers.com.

Note: The names of the Italians who died in this mine disaster were not included in the West Schuylkill Herald reporting. All of the twenty victims are recognized by name in a previous blog post. See:

Corrections and additional information should be added as comments to this post.