Part 1 of 4. On 28 April 1881, the trial of Henry Romberger and Frank Romberger for the murder of Daniel Troutman began in Dauphin County Court, Harrisburg. Here follows the reporting on the trial from the Harrisburg Telegraph, 28 April 1881 through 2 May 1881.

Note: The Harrisburg Telegraph spelled the surname “Romberger.”

For all other posted parts of this series of 4 articles, see: First Trial of Henry Romberger, etc.

________________________________

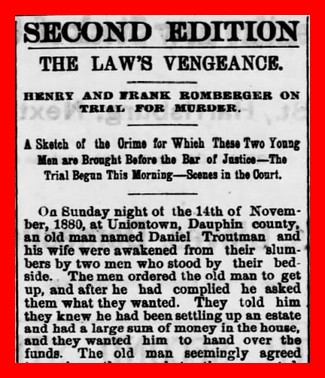

THE LAW’S VENGEANCE

HENRY AND FRANK ROMBERGER ON TRIAL FOR MURDER

A Sketch of the Crime for Which These Two Young Men are Brought Before the Bar of Justice – The Trial Began This Morning – Scenes in the Court

On Sunday night of the 14th of November, 1880, at Uniontown, Dauphin County, an old man named Daniel Troutman and his wife were awakened from their slumbers by two men who stood by their bedside. The men ordered the old man to get up, and after he had complied he asked them what they wanted. They told him they knew he had been settling up an estate and they wanted him to hand over the funds. The old man seemingly agreed to give them what they wanted, and pretended to make search for it. While doing so, and when the robbers were off their guard, he seized a shotgun and prepared to defend himself. The robbers, seeing this action, ran out of the house, followed by the courageous veteran. They ran around a corner of the house, the old man in pursuit, and disappeared in the darkness. Troutman returned to the door and as he was about to enter the house he turned and looked back, when one of the villains fired, the ball striking the old man in the left breast, making a fatal wound. He dropped in the doorway and was assisted into the house by his wife, who gave the alarm. Troutman lived but half an hour, and was conscious part of the time. In that time he repeatedly declared that the man who fired the shot was named Romberger, and that he lived at Tower City, Schuylkill County. In pursuance of this dying statement of Troutman, Henry Romberger was arrested. After his arrest, Henry Romberger made a statement implicating Frank Romberger, of Lykens, his cousin. A hearing was given the two men before Alderman Maurer, and the evidence being sufficient they were held for trial.

Thus the Rombergers fell into the clutches of the law, were indicted, and this morning were brought before the court to answer the grave charge of murder in the first degree. District Attorney McCarrell and ex-District Attorney Hollinger represented the Commonwealth, and Robert L. Muench, James Durbin and Simon S. Bowman attended to the interests of the defendants.

At 10:19, precisely, the district attorney moved the cases of the Commonwealth vs. Henry Romberger and Frank Romberger. Mr. Bowman asked for a continuance on the ground of the absence of material witnesses. Two of these witnesses the counsel said would probably arrive at noon. The third witness, a girl named Alice Doerr, could not be found. Another witness, named John D. Boyer, had been sent word by an outside person that he should not come. District Attorney McCarrell said an attachment could be taken out, served this afternoon, and the witnesses be produced by to-morrow, by which time the case of the Commonwealth will not have been closed. In addition, the District Attorney said, that if the defendants’ counsel would be put in writing what they expected to prove by these witnesses, the Commonwealth would decide in a few minutes whether it could go in by agreement. But the court said this is too grave to be conducted in that way. Mr. Durbin, in behalf of Frank Romberger, said he was ready to go to trial, if one witness after whom the sheriff now is, arrived. After consultation the Court said it was resolved that it should be decided at once whether Frank Romberger and Henry Romberger were to be tried together or separately and followed this by ordering the prisoners to be arraigned and to plead to the indictment.

The prisoners were then called before the court, when Mr. Durbin moved to quash the indictments on the grounds of irregularities in drawing the grand jury that found the indictments, and the panel of petit jurors in attendance at the present term. The irregularity charged is that the name and surname were not written out by the Jury Commissioners as required by law; in other words, that if the name of John D. Jones was to be put in the jury wheel it would have to be written John D. Jones and not J. D. Jones. Mr. Muench made an extended argument on the necessity of writing out in full the Christian name of men liable to be summoned as jurors. District Attorney McCarrell answered by saying that the act of 1834 made it necessary to write out the name and surname, but the act of 1867 only required the name to be written out. Finally the court decided that the venire and indictment could not be quashed for the reasons given, but jurors summoned by their initials alone could be challenged for cause and that given as the reason. The court would pass upon that question then. An exception was allowed the defense. The prisoners were then arraigned, they standing up while Prothonotary Mitchell read the indictment, concluding with: “What say you, guilty or not guilty?” Henry replied “not guilty,” and Frank “guilty,” in one breath; but Frank immediately corrected himself, saying “not guilty.” Mr. Muench then again moved for a continuance on the ground of the absence of material witnesses. The court at once overruled the motion, but Mr. Muench argued so forcibly and persistently for a change in the court’s view, that without reaffirming its decision a recess was taken until two o’clock.

After the Recess

The court reassembled at two o’clock. Judge Pearson announced that the trial should go on. The prisoners were then called to the bar and told that they had the right to challenge of the jurors called – twenty peremptorily, and as many more as they could show cause. The panel of jurors was then called over and the selection of a jury proceeded with, each one being sworn on his voir dire.

Jacob Painter, blacksmith of Susquehanna Township, had not formed and expressed an opinion as to the guilt or innocence of the prisoner, and was accepted as the first juror.

Henry Shrope, farmer, of Lower Swatara Township, had formed and expressed an opinion, but thought he could give a verdict according to the weight of the evidence. Afterwards he said he had conscientious scruples. Challenged for cause and challenge sustained.

John H. Hummel, farmer, of Hummelstown, had formed but not expressed an opinion. Challenged peremptorily by the defense.

W. G. Kinneard, justice, of Middletown, had not formed and expressed an opinion. Challenged peremptorily by the defense.

William Agney, laborer, of Steelton, had not formed and expressed an opinion, and had no conscientious scruples on the subject of capital punishment. He was accepted as the second juror.

Henry Raker, miller, of Uniontown, was challenged peremptorily by the defense.

Peter Bowman, gentleman, of Millersburg, had not formed and expressed an opinion, neither had he conscientious scruples on the subject of capital punishment. He was stood aside.

Joseph B. Landis, merchant, of Halifax, had formed and expressed an opinion, but might give a verdict on the evidence without regard to his opinion. Challenged peremptorily by the defense.

Michael E. Kerper, farmer, of Washington Township, had not formed and expressed an opinion. Challenged peremptorily by the defense.

Joseph Montgomery, forwarder, of Harrisburg, had formed and expressed an opinion but could give a verdict on the evidence, though his previous opinion might have some weight. Challenged for cause and challenged sustained.

John H. Rupp, farmer, of Swatara Township, challenged peremptorily by the defense.

Henry Summey, farmer, of Middle Paxton Township, had not formed and expressed an opinion, and was accepted as the third juror.

Cornelius O’Brian, farmer of Middle Paxton Township, challenged peremptorily by the defense.

Thomas Finn, miner, of Wiconisco, had formed but not expressed an opinion. He was stood aside at request of Commonwealth.

Uriah Rutter, farmer of Halifax, had formed and expressed an opinion, but could render a verdict on the evidence without regard to the opinion. Challenged peremptorily by the defense.

Frank Stevenson, bricklayer, of Harrisburg, had not formed and expressed an opinion. Challenged peremptorily by the Commonwealth.

Newton Noblet, teacher, of Halifax, had formed and expressed an opinion, but could give a verdict on the evidence alone. Challenged peremptorily by the defense.

Andrew Foltz, grocer, of Harrisburg, had formed and expressed an opinion, and if he went into the jury box would go in biased. Challenged peremptorily by the defense.

Edward Snyder, gentleman, of Harrisburg, had formed and expressed an opinion and could not go into the jury box unbiased. Challenged for cause by the defense and challenged sustained.

G. W. Baker, coachmaker, of Lower Paxton Township, was challenged because he had been summoned as a juror under the name of G. W. Baker instead of George W. Baker. The court said the challenge amounted to nothing, but if it was pressed, the doubt would be given to the prisoners, and the challenge sustained. The defense did not press the challenge, but challenged him because he had formed and expressed an opinion. Challenged for cause by the defense and the challenge sustained.

George Pancake, lumberman, of Harrisburg, had not formed and expressed an opinion. Challenged peremptorily by the Commonwealth.

Jonas Deibler, farmer, of Upper Paxton Paxton, did not understand the English language and was excused.

Richard Orndorf, storekeeper, of Wiconisco, had formed and expressed an opinion, but could give a verdict on the evidence alone. Challenged peremptorily by the defense.

W. S. Fortney, salesman, of Middletown, had not formed and expressed an opinion. He was stood aside.

John W. VanHorn, farmer, of Susquehanna Township, had not formed and expressed an opinion. He was stood aside.

George W. Freeeland, farmer, of Upper Paxton Township, had not formed and expressed an opinion. Challenged peremptorily by the defense.

Samuel Mumma, farmer, of Swatara, had formed and expressed an opinion, and might be a little troubled to render a verdict on the evidence alone. Challenged for cause by the defense and challenge sustained.

Charles P. Greenawalt, stonecutter, of Hummelstown, had not formed and expressed an opinion, neither had he conscientious scruples on the subject of capital punishment. He was accepted as the fourth juror.

Daniel Wagner, farmer, of Susquehanna, had formed and expressed an opinion, and could not give a verdict on the evidence alone. Challenged for cause by the defense and challenged sustained.

James B. Mersereau, lumberman, of Harrisburg, had formed and expressed an opinion, but might give a verdict on the evidence alone without regard to his previous opinion. Challenged for cause by the defense and challenge sustained.

H. W. Snyder, merchant, of Lykens, was called, but being a witness in the case, was excused.

Frank Fiddleg, carpenter, of Gratztown, had not formed and expressed an opinion. Challenged peremptorily by the defense.

Benjamin Romberger, gentleman, of Berrysburg, had not formed and expressed an opinion, and had no conscientious scruples. He was accepted as the fifth juror.

James Hipple, supervisor of Middletown, had not formed and expressed an opinion, and being without conscientious scruples was accepted as the sixth juror.

Ira Nissey, farmer, of Susquehanna Township, had talked about the case, but had not formed an opinion. He had no conscientious scruples was accepted as the seventh juror.

J. J. Miller, carpenter, of Williams Township, had not formed and expressed an opinion, neither had he conscientious scruples about hanging. So he became the eighth juror.

During the preliminaries both prisoners regarded the proceedings with great interest. Frank Romberger, the youngest of the two, sat near his counsel, Mr. Durbin. He was dressed in a dark suit of clothes, wore a standing collar and in his flat scarf was a large, square pin. His hair was combed down over his forehead, and slight side-whiskers and moustache relieved the pallor of his face. Altogether his appearance was much neater than when first arrested and placed in prison. He watched intently each juror called, and seemed relieved when any juror who had formed an opinion was challenged. Henry Romberger, the eldest, was dressed in a dark suit and wore a dark shirt. A thick moustache and whiskers covered the lower part of his face, and his hair was neatly combed. He was evidently very nervous, his eyes roving from counsel to judge and thence to juror, as if his fate depended on his catching every incident or movement. His stolid face would occasionally light up as a question was asked, and he carefully scanned the jury list as each new name was called. He sat close to his counsel, Messrs. Muench and Bowman, and occasionally would turn and look out on the crowd in the court room. Both of the prisoners were evidently gratified to be out of their cells.

__________________________________

From the Harrisburg Telegraph, 28 April 1881, via Newspapers.com.

Corrections and additional information should be added as comments to this post.