Part 4 of 4. On 28 April 1881, the trial of Henry Romberger and Frank Romberger for the murder of Daniel Troutman began in Dauphin County Court, Harrisburg. Here follows the reporting on the trial from the Harrisburg Telegraph, 28 April 1881 through 2 May 1881.

Note: The Harrisburg Telegraph spelled the surname “Romberger.”

For all other posted parts of this series of 4 articles, see: First Trial of Henry Romberger, etc.

__________________________________

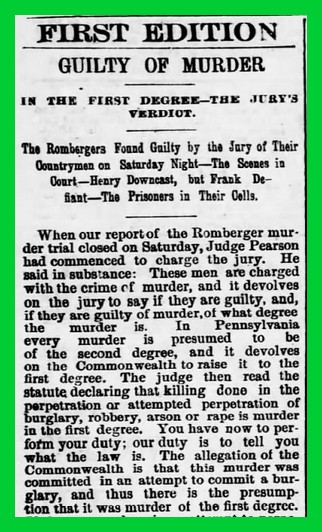

GUILTY OF MURDER

IN THE FIRST DEGREE – THE JURY’S VERDICT

The Rombergers Found Guilty by the Jury of Their Countrymen on Saturday Night – The Scenes in Court – Henry Downcast, but Frank Defiant – The Prisoners in Their Cells

When our report of the Romberger murder trial closed on Saturday, Judge Pearson had commenced to charge the jury. He said in substance: These men are charged with the crime of murder, and it devolves on the jury to say if they are guilty, and if they are guilty of murder, of what degree the murder is. In Pennsylvania every murder is. In Pennsylvania every murder is presumed to be of the second degree, and it devolves on the Commonwealth to raise it to the first degree. The judge then read the statue declaring that killing done in the perpetration or attempted perpetration of burglary, robbery, arson or rape is murder in the first degree. You now have to perform your duty; our duty is to tell you what the law is. The allegation of the Commonwealth is that this murder was committed in an attempt to commit a burglary, and thus there is the presumption that it was murder of the first degree. If the act was done in an attempt to perpetrate this crime then it is murder in the first degree. If not done in this attempt, then the act must be presumed to be murder of the second degree, but this presumption is often overturned and the murder shows to be of the first degree. The evidence here tends to show that these defendants were at the house of Daniel Troutman and tried to rob him. It is said they entered the house burglariously. It was at night. He and his wife and his children were in bed. It is said these defendants came in stealthily. The wife heard them. They came forward, and the one with the pistol demanded money. Troutman said he had no money. They said he had other people’s money and they were going to have it that night. He was alarmed at first, but afterwards took down his gun and ordered them to go. Finally they retreated and he followed them. He was in the line of his duty in following them. He would have been in the line of his duty if he had shot both, or had shot down one and beaten out the brains of the other. He followed them out and shot at one, and this one Henry confesses was himself. Immediately after there was a pistol shot from a No. 32 revolver, as was shown afterwards when the ball was found, and the wife looking out at the window saw her husband lying in the garden. A little while after the shooting the alarmed wife ran towards her neighbors. One of the men said: Let’s follow her. This shows they were around and were acquainted with the scene. Mrs. Troutman aroused the Gieses. They came over, examined the house and found no one. They then carried the murdered man and put him in bed. After a while he spoke, and when he inquired of as to who shot him, replied: “Hen Romberger shot me.” They then asked who was with him and he answered that he didn’t know, it was a stranger. This is a kind of evidence that often must be heard – the declarations of a person in the extremity of death. This man declared it was Henry Romberger and he must have known he was in the extremity of death. It is said now the persons who pursued this man were not guilty of murder, or of burglary, when they shot him. It is said they were running away and so were not guilty. I do not conceive such to be the law. Suppose persons attack men on the highway and attempt to rob them. The men resist and the robbers retreat. Suppose the robbers retreating were pursued, and firing at their pursuers killed on. I have no hesitation in saying they did the deed while attempting to perpetrate a crime. But did these men retreat when the wife went out some time after the shooting? They said, “there she goes,” which looks as if they were not ready to go. This leaves it for the jury to decide if they did not expect to rob the house. There is no doubt as to the attempt to rob at first, or that they did commit burglary in going into the house.

Now, who was there? The offense as described by the woman is murder in the first degree. If the jury believes the men were there intending to burglarize or rob, who were the men? Was Henry Romberger one of them? The evidence shows that the Wednesday previous he was at Troutman’s house to borrow money. He knew Troutman had money because he saw him get it at a sale a short time before. Henry knew Troutman had money because when Troutman said he had no money, the reply was you have other people’s money. Henry went to a town in Schuylkill County and hired a horse and buggy. He drove down to Lykens and there another man joined him. This is proved by five witnesses. They say the curtains were all down through the evening was pleasant. Two men were in the carriage because they were heard talking. The carriage then drove down towards Uniontown. The same horse and carriage were met along the road several times until Uniontown was reached. There they were recognized. Troutman lived four and a-half miles above Uniontown. Ultimately these persons got to Troutman’s, if the witnesses are to be believed.

Now, the confessions come in. It is said these confessions ought to be discarded. There is no reason I have heard why they should be. The confession is corroborated in every particular by Mrs. Troutman. In confession Henry tries to throw the shooting on Frank. But once for all let me say, if two men go out for a common illegal object, and one shoots while the other stands ready to assist, both are equally guilty. Of his murder. Were these men there? If the confessions are believed, Henry was there. These confessions cannot be used against Frank. Five witnesses say they saw Frank get into the carriage about five o’clock. Another witness says he saw the same carriage come back about eleven o’clock and a man got out and walked towards Frank’s house. This would amount to very little except in the chain of circumstances. If the burglary was committed and Frank was present – no matter who shot, both are guilty of murder. It is said these men didn’t mean murder. Probably not. Troutman running out and shooting at them does not palliate in the least their crime. They had no business there, and is they hadn’t been there this murder would not have occurred. The killing under the circumstances was clearly murder in the first degree. You must carefully consider one branch of the case as to Frank. A woman says Frank was at another place. An alibi is often set up – is of every-day occurrence. It is the easiest defense to make, if you can get persons to swear. The judge then referred to several cases of alibi within his experience. It is easy to be mistaken as to the day. How in this case? The woman tells the whole thing; but her husband comes here and says nothing of the kind occurred on this night, but that it did occur on the Sunday night before. You must judge whether the man or the woman is correct. Also whether all who saw Frank on this day are mistaken and this woman is right, or whether they are right and the woman is wrong. If you have any reasonable doubt give the defendants the benefit of the doubt. If you have no reasonable doubt, you must return them guilty in manner and form as the stand indicted, but be particular to state the degree.

The tipstaves were then sworn and at 6:30 the jury retired to deliberate on the verdict.

At ten o’clock on Saturday night the ringing of the court house bell announced that the jury had agreed upon their verdict. The streets leading to the court house were filled as if by magic with a rushing, yelling, pushing mob of excited persons, who besieged the temple of justice and sought advantageous positions that they might see and hear the last act in the trial of the two Rombergers. The rumor that the jury had agreed had reached the street sometime before the bell rang and the court house was already occupied by a number of persons. Consequently when the rush was made for entrance there was confusion worse confounded made by the noise of stamping feet and the pushing and loud talking of those who scrambled down the aisles. The tipstaves were no good in their efforts to keep order, and although they pounded on the floor with their poles and cried “Silence!” the crowd wouldn’t be silent until the room was packed with a steaming hot, perspiring mass of men, who stared at the judge on the bench and wondered what the verdict would be.

Shortly afterwards Henry Romberger and Frank Romberger appeared in charge of the sheriff’s officers, and were escorted to seats inside the bar. The rear door again swung open and the jury filed slowly in, taking their seats in the jury box. Clerk Mitchell told the prisoners to stand up, which they did, mechanically, Henry looking from the jury to the judge with a vacant stare, and Frank eyeing the jury sharply as if he would catch every word. Foreman Painter was then asked by Clerk Mitchell whether the jury had agreed upon a verdict, and replied that they had – a verdict of “guilty of murder in the first degree.” As the awful words were uttered Henry’s stolid countenance did not move a muscle. His eyes were fixed intently on the foreman in a set stare. Frank’s face flushed and he started slightly, then braced himself and setting his teeth he looked defiantly at the jury. “Let the jury be polled,” said Mr. Muench, one of Henry’s counsel. This was done by Clerk Mirchell, each juryman answering, “Guilty of murder in the first degree.” The crowd in the court room made no demonstration. It seemed to have discounted the verdict and were prepared for its public proclaiming. Messrs. Bowman and Durbin made a motion for a new trial and stated that they would file their reasons in a few days.

After this had been done, Mr. Muench shook hands with Henry and remarked, “Well, Henry, we did the best we could for you.” The same look remained in the prisoner’s face as he answered “Yes, sir,” in a melancholy tone. Frank remarked to his counsel that if they had put him on the witness stand he could have told something. “I know Dockey swore to a lie,” said Frank, excitedly, “I know I’m as innocent of that charge as an unborn babe. I’m perfectly satisfied.” Both of the prisoners were then led out to jail, and the jury was discharged with the thanks of the court.

At the jail, after the verdict, the two men as they reached the corridor stood looking at each other, but said nothing. They walked down towards their cells, Frank waiting for the door to be opened, but Henry shoving back the bolts and entering unassisted. Henry, in conversation, said he expected the verdict. He seemed very much downcast. Frank, on the contrary, was talkative and insisted on conversing with those outside his cell. His manner had totally changed from that of the afternoon when he cried passionately during an interview with his father. He was severe on Dockey and Williard, whom he said had sworn his life away, and said that if his advice had been taken there would have been more witnesses to establish the alibi. As the officers left the vicinity of the cells both prisoners said good might and lay down to sleep under the shadow of the gallows.

The members of the jury are reticent regarding the manner in which their verdict was made up, and say that they mutually agreed not to say anything about it. Enough has been made public, however, on which to rest the assertion that the jurymen had made up their minds on a verdict of guilty shortly after entering the room, but concluded, in order not to let it look like unseemly haste in so important a matter, to wait a while before going into court. At nine o’clock they got their supper and then sent word to the court that they were ready. They entered the court at 10:15 o’clock.

A TELEGRAPH reporter had a talk with Frank Romberger and Henry Romberger this morning, at the trap in the iron gate of each cell. Frank is bright, emphatic and voluble in his conversation, protesting his innocence with weeping, and declaring that if he is hung it will be the taking of an innocent life. His father, he said, would be here to-day “with the money to employ A. J. Herr to aid in the argument of his case for a new trial.” He had just finished scrubbing up the floor of his cell, and had his sleeves rolled up as if prepared for other work which he said he wanted to do this morning. Henry, who is several cells beyond Frank, when called to the trap in his iron door, looked gloomy and haggard, not in any degree as bright as Frank. He was eating peanuts, and seemed not disposed to enter into conversation, but when spoken to in reference to the verdict, said it was what he expected, but still hoped it might be for murder in the second degree. He had nothing now to expect but the sentence of the court.

__________________________________

From the Harrisburg Telegraph, 2 May 1881, via Newspapers.com. Corrections and additional information should be added as comments to this post.