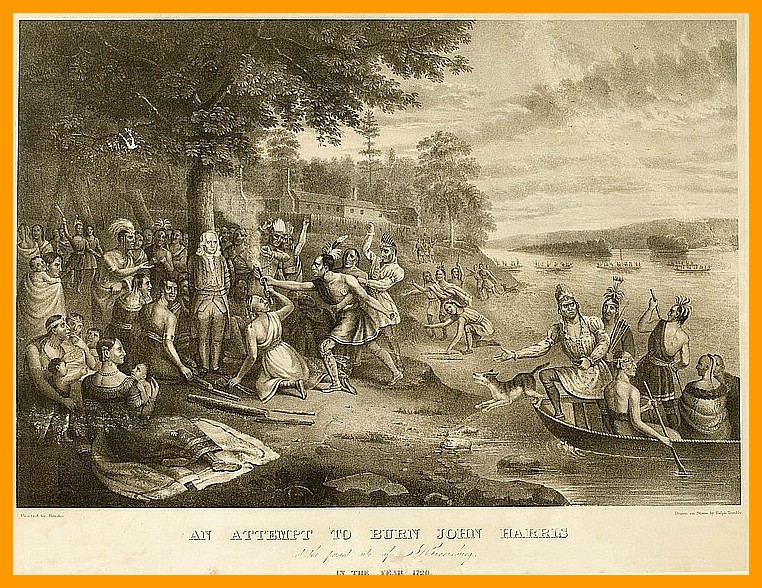

A story of how Indians attempted to burn John Harris and how he was saved.

The following column is from the Harrisburg Telegraph, 20 September 1895:

REWARD OF A KIND ACT

How an Indian Appreciated Shelter on a Rainy Night

[Dr. Robert Harris Awl, the oldest medical practitioner in Sunbury, contributes the following interesting article. The table the Doctor refers to was exhibited in the Pennsylvania Building at the Chicago Exhibition, and had been sent to the exhibition at Atlanta. After its return here it will be placed in the State Library.]

Dr. Awl says:

The announcement that the table prepared under the direction of the ladies of Dauphin County for the women’s building at the Columbian Exposition contains, among other interesting relics, pieces from the mulberry tree where John Harris was once bound by the Indians to be burned, reminds me of several historical facts connected therewith.

“John Harris, who was my great-great grandfather, was the first white settler on the banks of the Susquehanna River where Harrisburg now stands, and the father of John Harris the founder of Harrisburg. He kept a little store and traded with the Indians. One dark and rainy night a large Indian came to his cabin and begged for shelter. He was permitted to dry himself by the fire and sleep there, which pleased him very much. In the morning, by way of expressing his gratitude, as he could speak no English, he gave three loud whoops and departed. Nothing more was though of the circumstances at the time.

The Shawanese

“A few months after this a band of Shawanese (Southern Indians who had been driven north and had been taken under the protection of the Five Nations and located at Shawncetown, on the North Branch, now Plymouth) went down the river on a fishing expedition to Conewago Falls. On their return they stopped at Harris’ store and demanded rum. This he refused to give them, when they became enraged, and seized him, tied him to a mulberry tree and made preparation to burn him. They would have carried out their threat had not Hercules, a Negro slave of Harris, jumped in a canoe and paddling to the other side of the river, gave the alarm to the chief of a friendly band of Indians encamped there. They hurried across the river, drove the Shawanese away and rescued Harris. Their leader, or chief, it turned out, was the Indian whom Harris had given shelter by his fireside that rainy night a few months before. A painting is in existence representing Hercules as one of the stalwart figures in a canoe as the Indians were hurrying across the river. Some of my brothers or sisters, or their descendants, have the picture representing the attempt to burn John Harris, and a number of them have had Hercules painted in it which was not in the original. I have one in my office in which an Indian in one of the canoes has been metamorphosed into a Negro.

First Emancipated Slave

“This act of Hercules in saving the life of his master so pleased him (Harris) that he at once manifested his gratitude by giving him his freedom, and it is believed that Hercules was the first slave emancipated on the American Continent. Harris, when he died in 1748, was buried at the foot of this historic tree, and although scarcely a vestige of the trunk now remains, the grave of the pioneer may still be seen. His faithful Negro, Hercules, was also buried near him.

“This information came from the following persons, who are now all deceased: Mrs. Sarah Irvin, Lewistown, Pennsylvania, the last survivor of the Maclay family; Samuel Awl, Esq., born near Harrisburg, 5 March 1773, who married Mary Maclay, the granddaughter of John Harris, the founder; and William Maclay Awl, M.D., the eldest son of the last named, who was born in Harrisburg, 24 May 1799.

“And I may ass that I now have in my possession a small piece of the trunk of this famous tree, which was brought here by my parents when they came to Sunbury about the beginning of the present century. It has been, therefore, ninety-two or more years in the possession of our family. I was born 27 December 1819 near Sunbury and am now just entering on my seventy-seventh year.

Indian History

“It has been asserted by some writers that the Shawanese Indians were not here in 1720, when the attempt to burn John Harris was made, and it was some other tribe. But there is very conclusive evidence on record that they were here. On page 228, Pennsylvania Archives, 1664-1728, appears a letter from Governor Patrick Gordin, in the form of instructions to Smith and Petty, under date of 1728, who were about to visit Shamokin, on the upper Susquehanna, in which occurs this passage: ‘Tell Shakailamy particularly, that as he is not over the Shawanese Indians, I hope he can give a good account of them; they came to us only as strangers about thirty years ago; they desired leave of this Government to settle among us as strangers, and the Conestoga Indians became security for their good behavior. They are also under the protection of the Five Nations who have set Shakailamy over them,.’ This shows that the Shawanese were here at least as early as 1698, or over twenty years before the attempt to burn John Harris. It is very likely that he was rescued by a band of Conestogas as it appears they had become responsible for their good behavior.

“The original Five Nations were called the Iroquois by the French who found the ‘way back in the misty past’ on the banks of the St. Lawrence River, in Canada, where Montreal is now located. The Mohawks were supposed to be the oldest tribe. They settled in eastern New York upon the banks of the Mohawk River. The next in order were the Oneidas, who lived at the celebrated Oneida stone, or mass of rocks on the summit of a hill near the town of Stockbridge. The Onondages lived between the Oneidas and the Cayuga Lakes. Near to each other upon the beautiful lakes, which still bear their names, were settled the Cayugas and the Senecas. The last tribe which formed the Six Nations were the Tuscaroras, who came from the south.

The Father of Logan

“The Tuscaroras, it is said, were a branch of the original stock, the Iroquis. Shackallamy (now written Shikillimy), was the father of Logan, the celebrated Indian orator and Mingo chieftain,a and governing chief or vice king, stationed at Shamokin, now Sunbury, by the Five Nations to govern the Shawanese and other subjugated tribes. He wsa a great and good Indian, having been baptized in Canada by a Catholic priest at an early date. He was afterward converted by the Moravian missionaries at Sunbury, and adopting their creed and faith, died a Christina, 17 December 1748, and was buried in a wooden coffin in the Indian graveyard on the banks of the Susquehanna, near where Fort Augusta was afterward built. The Rev. David Zeisberger, a native of Moravia in Germany, who was sixty-two years a missionary among the Indians, was present at his death. David Zeisberger died at Goshen, Ohio, 19 November 1808, aged 87 years, (See the History of the West Branch Valley by John F. Meginnese, page 109).

“M. L. Hendricks, the antiquarian, of Sunbury, has many beads and trinkets which were taken from a grave in the old Indian burying place at or near where Fort Augusta stood, and supposed to have belonged to the celebrated Vice King (Shikelany). Among them is a knife tomahawk and a copper medal bearing the portrait of George III, and a piece of the coffin in which he was buried by the Moravians 145 years ago.

“Through ancestry as well as through historic associations, I claim and interest in the famous mulberry tree, and I submit the foregoing to show the line of descent and how I became the possessor of a small portion of the venerated trunk, which is sacredly treasured as a memento of the first John Harris. I congratulate the ladies of Dauphin County on their thoughtfulness in having a portion of the tree incorporated in their memorial table, for nothing more appropriate could have been selected to represent that portion of our State, and the thrilling incidents connected therewith.”

_____________________________

Transcribed from Newspapers.com.

[Indians]

[African Americans]