Part 7. The Nathan Henninger farm was located in Cameron Township, near Shamokin, Northumberland County, Pennsylvania. While four to six men were burglarizing Henninger’s stone house, a gunfire exchange took place, and one of the robbers was killed. Four men were later captured and put on trial in Sunbury in March, 1876. All four were found guilty and sent to prison. Another man, who testified against the burglars, was believed to have been involved but was never charged.

Follow the story as reported by newspapers of the time.

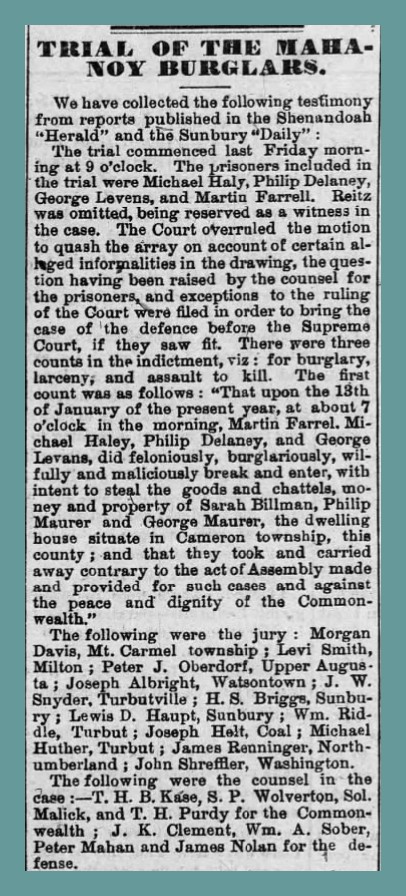

Featured photo (above) is the beginning of an article that appeared in the Sunbury Gazette, March 24, 1876.

From the Sunbury Gazette, March 24, 1876 (continued):

Sunbury, March 18 [1876] – The first witness placed upon the witness stand was the man upon whom the Commonwealth principally depends, Gilbert Reitz. Before Reitz weas allowed to open the ball, the defense moved that the opposite side put their offer in writing, and one whole hour was consumed in the performance of this by the Commonwealth, and the writing of the objections by the defense. Reitz, a solid sensible looking fellow, without any of the distinguishing marks of a bad character, all this time occupied the stand, and amused himself by looking as composed as possible, and straight ahead. He is a man of probably forty years of age, with a rather heavy looking head, and smooth face adorned by a small brown moustache. The Court having overruled the objections of the defense and filed bills of exceptions in their favor Mr. Wolverine for the Commonwealth proceeded to examine Reitz, and as his evidence is important, and will bear more heavily against the prisoners, we give it pretty fully:

Testimony of Gilbert Reitz

I lived on the 12th of January [1876], in Cameron Township, about three miles from Nathan Henninger‘s; am not much acquainted with defendants; had met them before the robbery about a year ago; in January 1875, I worked in Big Mountain drift, where Phil Delaney and I held a conversation about rich men. Old Joe Henninger was inside boss, and he complained that he had nothing to do except pay bail, in the presence of Delaney. Joe said that he lost considerable money on strangers but not on his brothers, who were not doing well, except Nathan, who was the richest man in the valley. Afterwards Delaney came to me and said that there must be a good many rich men in the valley. I said I did not think so. He asked me if Henninger was the richest man in the valley, and I said there were two old fellows who were richer. Then he said, “Let’s go over and take their money;” I said I didn’t want anything to do with it, when he said if if I I said anything about it I would get my brains blown out, and I promised to say nothing.

I left that place and did not see Delaney again until January, 1876; think on the 8th, and as I was crossing the railroad, I met a man who asked me if I saw Delaney; I said no, and he said that Delaney was looking for me. I said for what, and he said (objected to). Michael Haley is the man although I didn’t know him at the time. I said that I was going to May’s office to get some money. The office was shut, and as I was near the railroad crossing I met another man at that time I did not know, but found out afterwards it was George Levans. He asked me if I saw that man, and I said what man? He said the man I wanted to see. I asked him if he meant Delaney and he said no; told him that I was in a hurry, but would see him at Weaver’s; met him again at the crossing; and he said that Phil Delaney wanted to see me for a good while about that money. Haley told me this, and he wanted me to go along, but I said I wouldn’t; he said you show us the place and we will take it. I said I didn’t want to get into any scrape; he said I wouldn’t, that Delaney himself would go over and see about it. They said that they would come over on Saturday morning, and I said I wouldn’t show them the place, and he said I would get my share of the money. Michael Haley and George Levans I met at Boyer’s Tavern; went with them to about a quarter of a mile of the place, and showed them the roof. They took a look at the place and coming back told me that they would go there on Saturday or Sunday night, as just then they were not ready, or hadn’t met or guns enough. They went up the mountain and I went home. On Monday I went to Shamokin on business, and saw Phil Delaney; he told me that things were all right; then Farrell walked up to us – to me and Delaney. I never saw him before, but Delaney says, “This boy is all right;” and Farrell says, “Oh, yes, I’m all right, and won’t squeal, and would see anybody that squealed shot through the bars of the prison;” Delaney then told me that Haley was at work, and Farrell said that Levans had gone to Locust Gap to get more men and guns, and that one of these nights would go over. Well, that’s about all that I know about it. They said that, I should come to Shamokin after the affair was over, and that I would get my share of the money to the cent. Delaney and Farrell said that I would either get it in the woods, or from Billy McAndrew. Farrell said he had not or would never squeal. They said that any one who squealed would be shot. No threats were made against me in prison. Delaney told me I shouldn’t say anything about the affair (this was in jail), and that I should get my share; in the yad of the jail, Delaney said that one of us was enough to go to jail, if any. I asked him where the money was, and he said that was none of my business. Some of them came over to view the place on the Saturday before the robbery. They took a drink at Boyer’s Tavern. I didn’t see any of the defendants on Monday (the day of the robbery). The remainder of the witness’ testimony merely particularized the foregoing. Upon the close of the examination of the witness, which had been conducted by Mr. Wolverton, the defense asked the Court for the confession of Reitz, which had been offered as evidence.

The Court informed the counsel that the confession had been rejected, and that it lay with the Commonwealth whether the request should be complied with. The Commonwealth refused, and the cross-examination, conducted by General Clement, proceeded. Reitz was not materially shaken in any important particular throughout the entire cross-examination, which occupied several hours. He proved himself a sharp, shrewd man, as a witness, but did not impress his hearers with the idea that he was immaculate, but rather gave one to understand that he was a good-natured fellow enough, but with a liking for money, which he would be glad to get honestly, but if not in that manner, any way. In a clear manner, he sowed the several parts that each of the four prisoners took in regard to the preliminaries connected with the robbery, but was careful and cute enough to place the part that he took in the transaction in the best possible light. When asked by General Clement it he would not have taken his share of the stolen money had it been offered by him, he answered, “Of course I would, and, perhaps you might have done the same thing yourself.” This, of course, generated a loud smile, which, in addition to the answer, put the General on his mettle; but to no purpose, for Reitz had himself in hand, and kept himself so. The fellow must be of an exceedingly candid nature, for he seems to have told several people of his part in “the affair” before he left the State or was taken into custody. And he must be something of a walkist, as he didn’t seem to think that there was anything out-of-the-way in his walking from John Betler‘s house to his father’s place, a distance of twenty-three miles. He swore that he never received a cent of the money or knew where it was, but he had an idea of who had it, but for good reasons (we suppose) he wasn’t requested to divulge the name of the party or parties. According to his statement, after the job was finished, he was to receive his share of the money in the woods near Shamokin, or from Billy McAndrew, a gentleman who is unfortunate enough to be blessed with a decidedly bad character. He gave and account of his travels from the time he got scared, just after the robbery, until he gave himself up to the authorities in Canesteo, New York. It seems that he went from home to Sunbury, then took the train for Niagara Falls, and from thence went to Hamilton, Ontario, but having no money and not being able to get work, he footed it to Conesteo, where feeling sick at heart and, as he says himself, “troubled in conscience,” he gave himself up. He seems to be quite confident that if he regains his freedom he will be killed, but says that it will be his own fault, and that no one but himself would be to blame. Upon being asked if he were tried and acquitted last week on a charge of burglary, he answered no, but that such was the case this week, and also that he did not know before he was tried that he was to be acquitted. Altogether, Reitz showed himself to be what we might call a first class witness, and told his story to such a straightforward fashion, and stuck to what statements he made so undeviatingly that we are inclined and almost satisfied to believe that in the main he told the truth, almost if not the whole truth, and not much that was not truth, nor did we hear him breathe a sigh of relief, when, after occupying the witness stand for over three hours, he once more took a retired seat.

To be continued….

_______________________________________________________

Articles from Newspapers.com.

Corrections and additional information should be added as comments to this post.