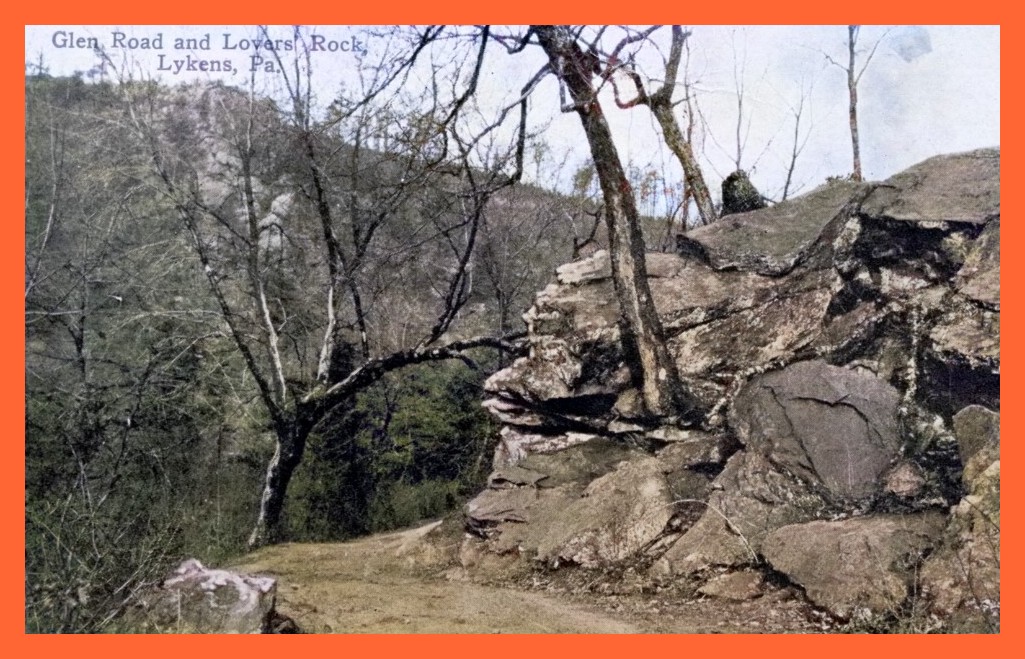

An undated, colorized post card view of Lovers’ Rock (also known as Love Rock), located on Glen Road, Lykens, Dauphin County, Pennsylvania. This rock is the subject of a legend involving Indians and early frontier brothers Harold Wingans and William Wingans.

It is believed that the legend was first put into print in an early edition of the Lykens Register. It was published in the Lykens-Williams Valley history by Allan Barrett in 1922 (available as a free download). Barrett gave an explanation of the origin of the story which included that a badly worn newspaper copy from the Lykens Register had been supplied to him by Lykens resident Edward L. Rowe who assisted in transcribing it. The Barrett history was reproduced in an edition sold throughout the valley for the U. S. Bicentennial in 1976, and it is from there that the author of a Harrisburg Patriot, May 27, 1981, article most likely condensed and paraphrased the story. The Barrett history, when it came to describing the Indians, was racist by today’s standards, particularly when it came to describing the peaceful people who were the original inhabitants of the area. Fortunately, the paraphrased version of 1981 omitted the worst racist references that Barrett embedded in his 1922 work.

From the Harrisburg Patriot, May 27, 1981:

______________________________________________

LEGEND LIVES ON FOR ‘LOVE ROCK’

By Lynn C. Schadle, Spotlight Correspondent

LYKENS — The story of Love rock does not begin on Berry’s Mountain, south of Lykens, but in New Amsterdam with the arrival of a group of young Englishmen before the American Revolution.

They left their native land to find wealth and adventure in the new world. Being anxious to start exploring the boundless uninhabited country, the young men stayed on Manhattan Island for only a short time, then separated and agreed to meet again in one year.

Among the group were fraternal twin brothers, Harold Wingans and William Wingans, 24. Since they held each other in high regard, when it came time to choose a traveling companion the two naturally chose one another.

For six months the brothers roamed the wilderness, living for weeks on end without seeing another person. They shelved their plans for seeking wealth and, captivated by the natural beauty of their surroundings, turned instead to hunting, trapping and fishing. At times they were required to defend themselves from the scalp-seeking Indians of the wilderness.

In their roaming, it wasn’t long before they arrived in the province of Pennsylvania, where they were completely taken by the beauty of the Susquehanna River and the valley it carved.

In following the river to the south, the brothers stumbled upon a party of Indians encamped along the broad river at a point where a narrow creek emptied into it. By being friendly and making a prompt show of confidence, the brothers were accepted and welcomed by the Indians.

They learned that this group was a small part of a much larger group of Indians encamped about sixteen miles to the east of the hills. After a short period of time, the Indians invited the brothers to travel with the, back to their main group for a feast.

The adventuresome spirit of the twins caused the to accept, and group set out shortly thereafter. Before noon they arrived at the encampment the foot of what is now Berry’s Mountain.

The brothers were struck by the appearance of the camp which resembled a permanent village. Bustle and confusion were present everywhere. Nude youngsters were playing with wild-looking dogs. Squaws and maidens were doing the camp chores as the warriors watched. In the center of the encampment was a ceremonial wigwam streaming with cloth of gaudy and variegated colors.

The brothers stopped at the edge of camp and contemplated the animated scene. They had seen quite a bit of Indian life during their rambles in the wilderness of America but never had they beheld such a commotion.

Within a short time, the brothers were approached by one of the group that had originally invited them to the encampment. The Indians told them that the chief’s adopted daughter was to wed his son that very evening.

Before long the Englishmen were conducted to a wigwam and served generous portions of venison and delicious trout. While eating, William remarked that he would like to have a look at her but said that he felt they should do their observing discreetly.

As the brothers strolled through the village, they were amazed to note that they seemed to be well accepted and were not in he [sic] least disturbed. Everyone was good-natured and the brothers soon were caught up in the gaiety of the occasion. Through the din and bustle they made their way to the decorated wigwam in the center of the camp. The place was guarded by several tough-looking braves. The brothers were lamenting their disappointment at not being able to see the future bride in a rather loud voice when they heard within a woman’s voice singing in excellent English. Harold had to be restrained by his brother or he would have dashed immediately to behold the owner of the beautiful voice.

They listened to the voice in astonishment and were shocked to hear that the words were not that of a song but, instead, the words of a story. The brothers were being told by this woman that she was a white girl, captured by the Indians, adopted by the chief and now being forced to marry his son. The Indian sentinels could not understand English so she sang the words to throw them off guard.

At that moment the brothers were startled by the appearance of the Indian chief and his handsome son. The Indians welcomed their guests but would not allow them to follow them into the wigwam of the white maiden. Harold was disappointed but resolved that they must rescue the girl as soon as possible. The ceremony was to take place that very evening.

The Englishmen split up and reconnoitered their surroundings. After a short time they met on the outside of the camp and, acting naturally, strolled back into the camp. They walked close to the gaily decorated shelter and outlined their scheme to rescue the girl in a loud enough voice for her to understand.

William further noticed that the Indians had whiskey and, after drinking for some time, would become roaring drunk. William’s prediction soon proved to be true but not as fast as the brothers wished. To accelerate matters, the two joined with groups of the Indians and prodded them to drink more and be merry.

It was a strange picture that the last rays of the sun fell upon in the Lykens Valley on that particular evening. With the disappearance of the sun the uproar of happiness and drunken revelry became very loud. The ear-splitting mixture was the combination of the howls of men, women and children, the melancholy howls of the dogs and the noise made by the primitive musical instruments – all in celebration of the marriage of the chief’s son.

Amid the confusion, the young girl slowly came out of the wigwam and, with a cherry [sic] smile, advanced to the young brave who was soon to be her husband.

At this point, Harold Wingans emerged from the bushes in the direction of a path that he had earlier followed up the mountain. He told William that the chief’s horse was under a big oak tree in the brush and that e was to be mounted within ten minutes and be ready to take the girl from his arms. from his mount he observed that Harold and advanced to a position about ten yards from the girl and her soon-to-be husband.

The girl, knowing her part, chose this moment to ask the chief it it might be permissible for her to pray privately to the Great Spirit, saying that she felt all was not well. The chief nodded his assent and the girl walked with bent head and slow steps toward where Harold Wingans stood concealed.

She did not know the exact location of the hidden Englishman until she heard a low hiss from the underbrush. She sank to her knees on the spot and commenced to pray.

In a moment, Harold was on his horse and scooped the rising girl into the saddle before him. The horse jumped the path and arrived at William’s hiding place beneath the brush. At that time, the loudest howl that has ever been heard in the Lykens valley was raised by the watching Indians.

“Quick, take her!” shouted Harold to his twin. “Follow the path up the mountain and keep on it until you are on the other side. I will take the road below and decoy them. See!” The last word called William’s attention to a blanket which was folded in the shape of a human form. Harold held it as he had held the girl. He recrossed the path and the Indians saw and followed him.

As Harold’s decoy deceived the Indians, William rode along the path higher and higher up the mountain. The path was well screened for the most part but before the two could gain any kind of a lead, they came to a clearing in the path.

Glancing behind him, William saw that he had been observed and was being followed. He urged the horse on but with the double weight that it was carrying, the horse soon became exhausted. William’s heart sank when he heard the crackling of twigs and branches behind him and realized that he was being closely pursued and the sturdy warriors might overtake him at any moment.

On reaching the top of the mountain, William found himself almost completely surrounded with only one way of escape from death itself. Just before him the hill came to an abrupt ending. At that moment he heard Harold’s voice call from below, “Jump the horse over, and keep well on him; they have wounded me to death.”

William, not stopping to think any longer, turned his horse’s head toward the cliff and jumped. The horse struck the ground like a piece of lead and William sprang off with the maiden, glancing at the horse to see him dead.

William plunged into the thicket with the girl and was able to make his escape. Fortunately, the two met up with a party of settlers in the morning.

The sad part of the story is that old chief’s son did love the maiden and he mourned her for months to come. He led many a fruitless search for her throughout the wilderness but turned up nothing. In time he began visiting the spot where the miraculous leap took place.

One day, coming down from the precipice to his people, he was laughing and singing love songs. His hair was decorated with bright flowers and pretty grasses as he danced throughout the camp. His people stared in surprise at him but his father, now feeble and ill, looked at him and fell back dead. His heart was broken to see his noble son now so hopelessly deranged.

The tribe chose this time to leave the valley but could not persuade the chief’s son to accompany them. He climbed the precipice one more and for five years he lived and labored there. During that time, it is said, he cut two large recesses out of the solid rock. In one of these, the broken-hearted lover sat and waited for his live to return.

Ten years later, William Wingans brought the Indian’s intended bride, now his own wife, to the wilds of the Lykens Valley on a hunting party, They returned to the spot where the jump was made and looking down, saw the Indian waiting for Mrs. Wingans.

The chief’s son smiled at her and motioned to the empty recess beside him. Then he laid back and closed his eyes.

When Wingans reached him, he found the Indian dead. From that point to this in local lore the name of the spot has been “Love Rock.”

__________________________________________________

An early version of the Love Rock story was found in the Lykens Register, September 1, 1898; this may be the one that was referenced by Barrett, without giving a date. It was repeated in the Lykens Standard of October 10 and October 18, 1924. A poem version by Daisy Rowe appeared in the Lykens Standard of May 3, 1935.

See also:

The Harrisburg Patriot article is from the on-line resources of the Free Library of Philadelphia.

Corrections and additional information should be added as comments to this post.