Part 5 of 6. In October 1881, new trials began for Henry Romberger and Frank Romberger, who had been previously been convicted of the murder of Daniel Troutman; the new trials were granted because of problems with the instructions the judge gave to the jury in the first trial. In the end, both were again found guilty of murder in the first degree. This series of posts follows the second trials through to their conclusion, including the death sentences imposed by the court. The newspaper articles describing the trials are from the Harrisburg Telegraph.

For all other parts of this series on the second trials, see: Second Trials of Henry Romberger, etc.

For all parts of the series on the first trial, see: First Trial of Henry Romberger & Frank Romberger.

________________________________

From the Harrisburg Telegraph, 21 October 1881:

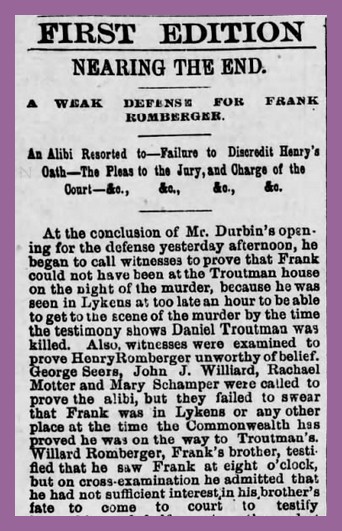

NEARING THE END

A WEAK DEFENSE FOR FRANK ROMBERGER

An Alibi Resorted To – Failure to Discredit Henry’s Oath – The Pleas to the Jury, and Charge of the Court – &c., &c., &c., &c.

At the conclusion of Mr. Durbin’s opening for the defense yesterday afternoon, he began to call witnesses to prove that Frank could not have been at the Troutman house on the night of the murder, because he was seen in Lykens at too late an hour to be able to get to the scene of the murder by the time the testimony shows Daniel Troutman was killed. Also, witnesses were examined to prove Henry Romberger unworthy of belief. George Sears, John J. Williard, Rachael Motter and Mary Schamper were called to prove the alibi, but they failed to swear that Frank was in Lykens or any other place at the time the Commonwealth has proved he was on the way to Troutman’s.

Willard Romberger, Frank’s brother, testified that he saw Frank at eight o’clock, but on cross-examination he admitted that he had not sufficient interest in his brother’s fate to come to court to testify in his behalf at the last trial. William Gemberling, Joseph McAllister, Dr. W. J. Smith, W. H. Kemble and Alfred G. Stanley were called to prove that Henry Romberger’s general reputation for truth was so bad that he could not be believed on oath, but they all acknowledged, with the exception of Dr. Smith, that they had never heard Henry’s veracity questioned. H. C. Demming, the court stenographer, was then put on the stand to contradict his notes Mary Kenter’s testimony. Court then adjourned.

This Morning’s Session.

Josiah Romberger, the father of the defendant, was then put on the stand and testified that for nineteen or twenty months previous to July 1880, Frank was in Delaware. This was to contradict John Dietrich who swore that he had seen Frank of and off for two years previous to the murder. On cross-examination the witness said Frank went away November, 1879, and returned July, 1880.

Willard Romberger then testified that Frank went away from Lykens December 1878, and returned July 1880. On cross-examination the witness got slightly mixed, being unable to give the name of the place in the State of Delaware where he swore Frank and he had been together.

The defense here closed, and the Commonwealth having no rebutting evidence, Mr. Hollinger went to the jury with a statement of the facts on which the Commonwealth relied for conviction. He gave a plain statement of the evidence as developed by the witnesses, and explained to the jury applicable to the case. He then took up Henry’s testimony, sentence by sentence in every detail by disinterested witnesses.

Mr. Durbin then made the closing argument for the prisoner. After reading some authorities which did not have much relevancy to the case, counsel said that discarding Henry’s testimony, there was nothing on which to convict the defendant. He then reviewed the testimony, being very strenuous in his efforts to convince the jury that Henry was unworthy of belief. It was further argued that murder was not intended, because the old man was not killed in his bed room. Taking all the evidence as presented, and excluding Henry’s evidence as not being corroborated, counsel claimed the jury could do nothing else than acquit, or, at most, find Frank guilty of murder in the second degree.

District Attorney McCarrell closed for the Commonwealth in an eloquent manner. He reviewed the evidence in the case, and charged the shooting of old man Troutman upon Frank Romberger. Frank’s connection and participation in the crime, he said, had been proven not only by the witnesses for the Commonwealth, but they had been corroborated by some of the witnesses called by the defense. He asked that the jury bring in a verdict of murder in the first degree , as being in consonance with the powerful evidence produced. Mr. McCarrell’s speech occupied an hour and a half in its delivery, and at the conclusion court adjourned until two o’clock.

At two o’clock this afternoon Judge Henderson took his seat on the bench, and the jury, having had their dinners, filed in and took their seats. Shortly afterwards Frank Romberger came, attended by the sheriff’s deputies, and took a seat by his father, who had been waiting on him.

Judge Henderson when charged the jury. He told them to be cautious and clear in weighing the evidence, and to let no fear of consequences swerve them from their conviction. The degrees of murder were clearly explained, the Judge dwelling particularly on the phrase “malice aforethought.” The testimony in the case was reviewed at length and carefully explained in all its detail. “If you find that the life of Daniel Troutman was taken during a robbery or an attempt to rob, then it is murder in the first degree.” The question of an alibi, as defense endeavored to prove by Frank’s brother, was passed by. The question of whether these men were fleeing when the shot was fired has been raised. None of the evidence was to that effect. On the contrary, they lingered in the vicinity of the house after the old man was shot, and were there when the wife came out of the house. It is of little consequence who fired the shot if both were present in pursuance of a plan to rob. Both would be equally guilty, in the event of the death of the man shot. The old man had the right to use every means to expel the intruders from his premises, even to killing them. The man who fired the shot was armed – the pistol had already been presented at the breast of the old man. Is it not the natural inference that Frank intended to use his weapon? He had it with him and had an opportunity to escape. It is said that Henry Romberger’s evidence should be disregarded. It was supported by other witnesses and is in harmony with the facts brought out by the Commonwealth. It is for the jurors to say what weight it is entitled to. Very little evidence was brought out that was damaging to Henry’s reputation for truth. The points submitted to the court by prisoner’s counsel were then taken up and answered at length.

At three o’clock, after Judge Henderson had finished, the jury retired and the court room was rapidly emptied of the large crowd of spectators.

_________________________________

From the Harrisburg Telegraph, 22 October 1881:

DOOMED MEN

HENRY AND FRANK ROMBERGER, THE MURDERERS

The Jury in the Case of Frank Romberger Find Him “Guilty of Murder in the First Degree” – Remarkable Nerve of the Condemned Man.

The jury in the case of Frank Romberger left the box yesterday afternoon at three o’clock, after a very careful charge from Judge Henderson, wherein their duties were fully explained. They entered the jury room and immediately prepared for business. Their first ballot resulted – 10 for murder in the first degree and 2 for murder in the second degree. The same result followed the second ballot. The third stood 11 to 1, and this result continued until the end of the eighth ballot, the balloting proceeding at intervals as the hours wore on, there being a consultation after each vote. On the ninth ballot it was 10 to 2, and on the tenth it was unanimously agreed to find a verdict of murder in the first degree. At half-past six o’clock the sheriff was notified that the verdict was ready and the jury was anxious to appear in court. Judge Henderson and Pearson were notified and soon appeared, and the prisoner brought into the court room from jail. The first tap of the court house bell sent men running from all directions, and in a few minutes the court room was filled with an eager, scrambling crowd of curious people, all anxious to catch a glimpse of the unusual scene. Several times the tipstaves shouted order, but there was very little order observed.

“Frank Rumberger, stand up,” said Clerk Mitchell.

The prisoner arose. Not a muscle quivering. He eyed the foreman of the jury intently, but not a trace of emotion was visible in his countenance. His face, perhaps, was a trifle paler, but outwardly he gave no sign of the terrible emotion that must have been raging within.

“What say you gentlemen of the jury; have you agreed upon a verdict?” asked the clerk.

“We have,” came the response. “Our foreman shall answer for us.”

“What say you, Mr. Foreman; do you find the prisoner at the bar. Frank Romberger, guilty or not guilty?”

“Guilty, and in the first degree.”

As the awful words were spoken the prisoner did not shudder. His wonderful nerve held him up. He was game to the last and there was that in his remarkable stoicism that challenged admiration.

Ovid F. Johnson, Esq., in the absence of Mr. Durbin, Frank’s counsel, asked that the jury be polled, and the prisoner eyed each juror as the fatal words were pronounced.

As the conclusion the jury was discharged by Judge Henderson and left the room, the vast crowd rapidly following and lingering about the rear door. Frank clapped his hat on the back of his head and then held up his hands for the nippers to be placed on his wrists. He said nothing, until on the way to jail he remarked to one of the deputies it was all up now, and greeted Mrs. Duey with the same remark.

The verdict is considered by everybody who has heard or read the evidence as a just one, the circumstances connected with the murder of old man Troutman being peculiarly atrocious.

Court has adjourned until next Wednesday, when the prisoners will probably be sentenced.

FRANK ROMBERGER’S STORY

Where He Claims to Have Spent the Sunday of the Murder

A TELEGRAPH reporter passed an hour with Frank Romberger, in his cell, this morning, for the purpose of listening to what the condemned man had to say in reference to the crime, for the perpetration of which he has been convicted. He is the same spirited , voluble, emphatic man he has ever been, protesting his innocence in statements to show where he was on the night of the murder of Daniel Troutman.

Reporter – Good morning, Frank.

Frank – I am glad to see you; take a chair.

Reporter – The end is coming, Frank, and you case now looks very gloomy.

Frank – It does, but I am innocent of all wrong to Daniel Troutman.

Reporter – You maintain your innocence, Frank, and assert you were not with Henry Romberger, and did not accompany him to Daniel Troutman’s on the night of November 14, 1880.

Frank – I was not – did not see him that day.

Reporter – When did you see Henry last?

Frank – About 9 o’clock A.M., Saturday, November 13, 1880. I was then with Charley Brinton, coming from Henry Slayder’s store, with my pay for the month of October. We went to the barber shop opposite the Odd Fellows’ Hall, from where we went to the shoe store of J. B. Moyers, who I paid $10.35. I asked Brinton to go to the saloon opposite to get beer, but he declined, saying he wanted to see Joe Davis, at the corner. Henry Romberger was standing at the Odd Fellows’ Hall. He called me over. I went. He opened a side door leading to the yard. We entered, and when inside he asked me to loan him $10. I told him I could not under any circumstances. I showed him $25, which I had for a shooting match on the 27th of November, when he pressed me to loan him $5, in return for which he would bring me twenty or thirty pairs of birds on the following Wednesday. I still declined to loan him money, and he came down to $1, which I refused to give him. He then said he would tell me where I could get $8,000. I asked where, and how, and why he did not get it? His reply was that he could not himself open the safe in which it was. I then asked how he knew it was in a safe. I then asked how he knew it was in a safe. He said his mother had a little girl about nine years old, whom she had taken to a doctor in Tremont to have her mouth examined, when the doctor told her to open her mouth, and if she sat still while he operated on it he would show her a nice pile of money. The girl did as the doctor wanted her to do, when he opened his safe and showed her $8,000 in bank notes in a tin box. Henry’s mother told him this story, and advised him to steal it, as it was easily gotten. She said Henry should get some one to help him, a man to watch outside while he entered and stole the money. I told Henry I did no such business. He said, Frank I know you have done such things before. I asked him how he knew it? He said by other people’s talk. I denied it. He then said, “if you get this money you need only give me $500,” but I refused his offer, when he said he would be satisfied with fifty dollars. This I also refused, telling him I had work at good wages, and was earning all the money I wanted in an honest way. He then in an angry tone, said: “Very well, I’ll get even with you for refusing to help me in this job.” We then had some hot words, but I told him he could not harm me. He again asked me for one dollar, which I refused, but told him I would treat him to all the beer he could drink. He left me, going out the back way. I returned by the way I came and re-entered the saloon, when I put a dollar on the bar and asked the boys present to come and drink, Henry, being there and drank three glasses. He advised me, as I was leaving the saloon, to keep mum about the $8,000. I made no reply, when he left the saloon before I did. Charley Brenner and my father entered as Henry went out, when we had more beer. This was on Saturday, November 13, 1880. I did not see Henry again until I met him at Alderman Maurer’s office in Harrisburg, Monday, November 22, 1880.

Reporter – Then you did not see Henry on the day or night of the Troutman murder?

Frank – Turning quickly to the reporter and looking at him steadily in the face, with a blank, inperturable stare said, “No sir.” Closing his lips down very firmly at the utterance of the no. “I got home on Sunday morning, November 14, 1880, about three or four o’clock, and at once went to bed, from which I did not rise until two or three o’clock P.M. After taking my dinner and starting to go out, my wife called to know where I was going, and I said down town. She asked me to go with her to my father’s, and I told her I would when I got back. She told me she had no faith in my promise, when I said to her, we’ll go up on Monday, which did not suit her as she had to wash on that day. We then parted, with a kiss, as usual. I went down town, stopped at Barrett’s corner in company with Charles Schoffstall, Evan Harris, Jacob Smeltzer, Henry McCoy, Jacob Hoffman, and others. I stayed at the corner for an hour or more – then went down town to fulfill a promise I had made with Ida Haines, to go out walking that evening with Mrs. S——-g; but her husband was at the window when I got to the house, and I passed on; returning I again passed, but Mrs. S did not come out. I met John Milliard on Charley Morts’ corner. He inquired about Jacob Reddinger. I told him I had seen him, and where he went. He left, when Mary Kinter came out of her house, and asked where my wife was, I said at home; my wife’s sister was at Kinter’s, and asked about my little boy, who I said was at his grandfather’s. I then went to Barrett’s corner, where I spoke to Mr. Barrett and a number of others, and when I left it was about sundown. I proceeded to Charles Brinton’s house, where I saw his wife and sister and asked him to take a walk, but he declined because he had promised to stay at home and give the girls an oyster supper. I went down the road and met Lewis Kelly and Jacob Searer, who were in a carriage, and I spoke to them. A woman stopped before me. She came from the woods. I walked ahead to see her, but could not recognize her. I then returned to Barrett’s corner, meeting Henry Searer on Irving’s corner. This was about 6:45 P.M. I then went to Stanly’s corner, went to the drug store and got cigars, and as I got back to the corner Dr. Smith, with Clay Sherbin, drove up, the latter slighting. Dr. Smith spoke to me and I replied. I again went to Barrett’s corner and had a talk with Lawrence Glessig about Delaware, and with Obediah Reigel about his grandfather, who had been buried that day. I left and went down street, and met my brother, to whom I gave a segar, and inquired about the folks at home. He asked me where I was going, and I said to Ida Haynes’, and I passed on over to Ida’s, crossing the commons to get there. As I entered Ida inquired the time when to mislead her, I said between six and seven o’clock. We met in the kitchen, but soon went to her bed room, where I stayed for about an hour. When we got to the kitchen it was 9 o’clock. She showed me notes of money due her, that she had loaned different parties in sums from $300 to $700. Ida and I remained in the kitchen about forty-five minutes. As I was leaving she asked me if I had seen Mrs. S. that night, and I told her I had not. When I left Ida it was about ten o’clock, as near as I can tell, and I went direct home, walking slowly. When I reached the town I met two young ladies; one a Miss Clara Snyder, who was accompanying the other to her home. I can’t recall now who she was, but I think she is a daughter of Mrs. Schuler, or a young lady who is in Lem Lowe’s block. When I got into my own house and was in bed, I looked at the clock, and it was 10:45 P.M. My wife asked me when do you want your breakfast? I said seven o’clock.

This statement was made by Frank in an emphatic tone, and with a very pleasant manner.

Reporter – This accounts for your whereabouts when the Troutman murder was perpetrated?

Frank – It does, and every word I tell you is true, so help me God, and I will maintain it with the rope around my neck, if I am to hang.

Reporter – You had a fair trial.

Frank – I did – the judge was fair, but the jury found a verdict on perjured testimony. Henry Romberger swore to a lie in all he said about me.

At this point Frank’s father came into the cell, and the reporter left.

___________________________________

News articles from Newspapers.com.

Corrections and additional information should be added as comments to this post.