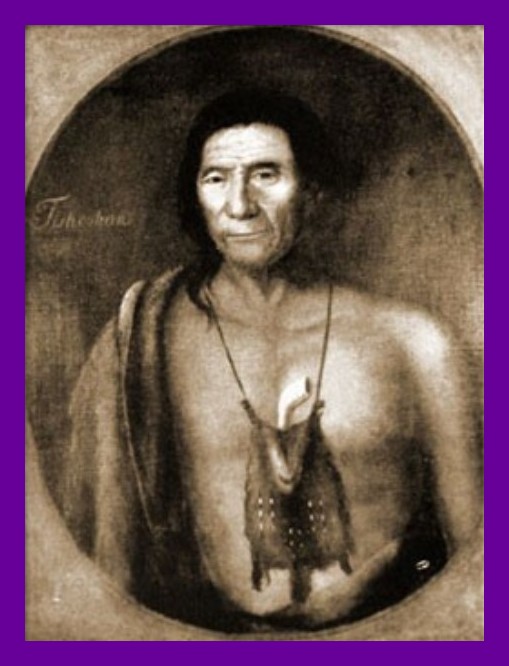

From Teedyuscung‘s Findagrave Memorial:

Teedyuscung was known by the whites as the King of the Delawares because of his unusual abilities and influence among the Indians in the Lehigh, Susquehanna and Delaware River valleys.

He was the son of Capt. Harris and was a broom-maker. Teedyuscung participated in the Treaty of Easton which resulted in the loss of any Lenape claims to all lands in Pennsylvania.

________________________________

From the Souvenir Book for the Millersburg Sesquicentennial Celebration (1957):

TEEDYUSCUNG

Teedyuscung early in life found the fishing exceptional in the Mahantango Gap north of Millersburg. In peaceful, care-free days he spent much time at the foot of the mountain enjoying his favorite pastime.

But more serious task fell to his lot in later years. His people, the Delawares, had been subjugated by the powerful Iroquois Confederacy about 1700, to such a degree that the Iroquois frequently reminded them that “we made women of you.” This situation continued until the early 1750s, when the Iroquois, for reasons appearing best to them, granted the Delawares a greater degree of autonomy, at least tacitly.

This situation fitted the talents and temperament of the crafty and scheming Teedyuscung about as well as a tailored suit fits a Hollywood actor. From then on the Delaware chief played the White Man against the Iroquois Indian, and vise versa, playing both sides of the street to the advantage of the Delawares, and more especially to the advantage of his own hero, Teedyuscung.

So successfully had he cultivated the whites that they built him and other prominent Indians English-style homes in the Wyoming Valley, a region set aside for them by the Iroquois Confederacy. Here he was indeed living like a king, enjoying his firewater for which he had a passion even greater than fishing. And why shouldn’t he? Had he not conferred upon himself the title of “King of Ten Nations?”

On the evening of April 19, 1963, while he was lying in a drunken stupor in this English-style residence, unknown incendiaries set fire to his home, as well as to the who village, and Teedysucung‘s home was a roaring pyre, with the great chieftain perishing in the flames.

What to do with the late King that would be keeping with his greatness became a question for serious discussion by his subjects. Also where would his Spirit find its greatest repose and happiness?

During a lengthy Council, Schela, the daughter of his intimate friend Quiquingus, proposed that his remains be interred at the foot of the Mahantongo, where he had spent so many happy hours indulging in his favorite pastime.

The suggestion was unanimously approved and preparations for the long trip down the Susquehanna were made. After properly dressing the King in war clothes, they placed him in a canoe, and, accompanied by a flotilla of canoes, began the sad journey down the river. The trip was apparently uneventful until they came to Shamokin (now Sunbury), where the garrison of Fort Augusta fired upon them, killing one squaw in the funeral party.

When the party reached the foot of the Mahantongo on the left bank of the river, they disembarked and commenced digging a grave for their dead chief. While they were thus engaged, thunderheads were forming in the western sky, No sooner had the great chief been laid away the elaborate ceremonies than the rapidly-forming storm burst in all its fury at the close of day. Indescribable thunder and lightning, accompanied by a violent wind and torrential rain, caused the Indians to huddle up against the foot of the mountain for at least a minimum of shelter. While the storm was at its height, a crash of thunder, the like of which the Indians had never heard before, shook the mountain to its lowest foundations. An instant later an avalanche of rocks, loosened by the elements, was hurled down from the summit, almost burying the Indians below. Fortunately, all were spared.

The storm continued with unabated fury until morning, when preparations for the return trip were made. One Indian, inadvertently glancing up at the summit of the mountain, beheld the face of their dead chief sculptured there in rock by the very forces of nature which had so nearly united them in death with their departed king.

For these almost two hundred years Teedyuscung in stone has kept his watchful eye trained upon his beloved fishing place below. Do you wonder what he thinks of his white brethren who despoiled the waters of the Susquehanna River with sewage and mine and factory wastes to such an extent that the fish no longer frequent its waters in as bountiful numbers as they did when he was here in the flesh?

Note: Teedyuscung‘s head cannot be seen from the highway. To see it one must go north of town slightly beyond Tarry Hall, the residence of Mr. and Mrs. Harl H. Heckert, pass through the open span of railing, cross the railroad tracks and walk north about 150 feet. The likeness is not so good as [Simon] Girty‘s face across the river.

__________________________________

The story appeared in the Souvenir Book for the Millersburg Sesquicentennial Celebration, published in 1957. For availability of copies of this book, contact the Millersburg Historical Society.

Corrections and additional information should be added as comments to this post.

[Indians]