A story of an unsolved murder of a Lykens man in 1889 with his reminiscences of life in Lykens at the beginning of the Civil War. This blog post, by Jake Wynn, first appeared on the Civil War Blog on May 29, 2013.

_________________________________________

A rare thing is to hear the Civil War years as described through the eyes of a child who grew up in the shadow of the war.

Dr. Charles H. Miller, originally of Lykens, gives us that exact thing in a book he published as a young college graduate of the University of Pennsylvania medical school.

Born around 1850 in Lykens, Charles was the last of three sons born to Joseph Jonas Miller, a wealthy land surveyor and Dauphin County clerk, and Barbara Hoffman. It is likely that the family also held a house and property in Gratz as well, as several documents attest to this ownership. However, for this post we will focus on the Lykens connection. His account of growing up in Lykens during the 1850s is captured in a short story, titled, “Lykens, Twenty Years Ago: An Historical Sketch,” and was published by the Lykens Register in 1876. Dr. Miller describes the life and adventures of a young boy growing up in a developing coal and transportation hub. The text is an incredible asset for anyone researching the early years of the town, and within the pages of this text, many names and interesting facts can be gleaned.

Near the end of the text, Miller goes into describing some of his final days as a boy in Lykens, before his family moved to Harrisburg and his father took up the position of Dauphin County clerk. The most likely time period for the events described is during the early months of 1861.

Twenty years ago the glory of the Battalion Day was just in its wane. For more than a half century its lustre was a thing of renown and its name a guiding star of the almanac. The threats of secession in the South, the mutterings of war in the North attracted the attention of the country to something more defensive than pop-beer and ginger-bread, and the grand strut of the militia captain, awing and soul inspiring upon that all conspicuous day, had lost its fear and importance in the impending crisis.

The last of such days was held at Lykens at this period. The woods, for many acres square upon what is now North Second street, beyond the railway embankment, were hewn down and removed, and the undergrowth of shrubbery burned to the surface. The tent-pole took the place of the sapling and the flag-staff and canvas crowned the scene. Never before had the village enjoyed so much importance. The war horse danced and pranced before admiring multitudes in the street, snuffing danger afar off. From his glossy sides, like a thing that had grown from him, towered the brave commander, stiff with silent grandeur. How our heart went up and our breath came fast and thick at the sight of this august personage! His extensive epaulets, glittering sword and gorgeous plumage upon his hat! If we could have exchanged our lot with any one in the wide, wide world at that moment, it would have been with that statue of pomposity at the head of such magnificence.

Every fresh arrival of militia brought with it its own brass band or drum corps, which struck up a lively strain the moment it entered the village, and only ceased after breath became an object of extreme solicitude. Every fresh arrival also brought to the doors all the village that could contain itself, and with it such an aroma of cinnamon and ginger as brought tears of anguish to the nose of the visitor and such friendliness of heart and head as extended its own welcome anywhere. The streets were a holiday attire; and root beer was only two cents a glass. The amount of cake that could have been bought for a penny at any of the numerous stands, would have disgusted the stomach of an elephant.

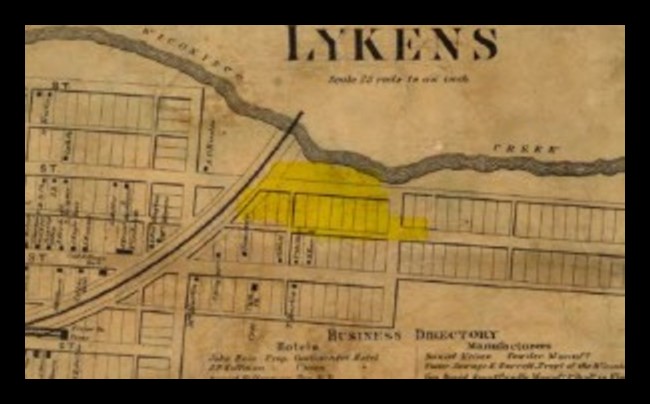

Several very important facts can be retrieved from Dr. Miller’s boyhood memories. An interesting line points to the location of the militia’s parade ground and encampment.

The woods, for many acres square upon what is now North Second street, beyond the railway embankment, were hewn down and removed, and the undergrowth of shrubbery burned to the surface. The tent-pole took the place of the sapling and the flag-staff and canvas crowned the scene

Section adjacent to North Second Street and railroad embankment. Possible site of parade ground and encampment.

Another important item that Miller points out is just the sheer importance of this community to the region during the time of crisis. The Lykens of 1860 and 1861 was a fast growing community of over 3000 people, according to the Census of 1860. The coal trade and railroad were proving to be a profitable business, and the town was the staging area for all mining operations located within the Lykens and Williams Valley region. With war looming on the horizon, Lykens became an important marshaling point for local residents who wished to volunteer for the Union army. Much can be taken from even the smallest details of the young man’s remembrances of one of the most critical moments in the history of the nation.

Now for Dr. Charles H. Miller, life took a turn for the worse following the publishing of this text. The opening page of the document states:

Read before the Lykens Harmonic and Literary Association, Friday evening, December 22, 1876.

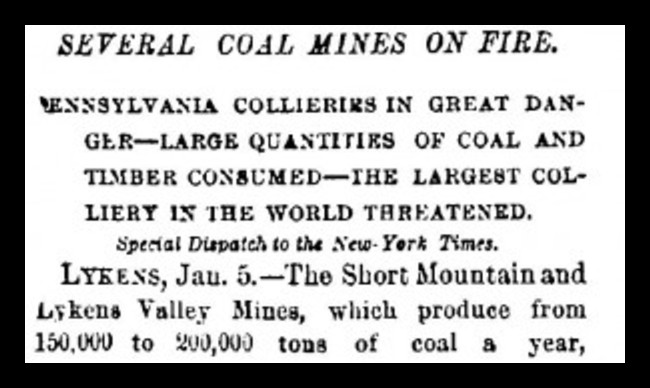

Miller’s promising writing career would be choked off only a few days after he read this book before a group of local citizens. A fire on New Years’ Day 1877 in the Lykens Valley Slope, located in the colliery above Wiconsico, shut down the mines for nearly a year. Not one shipment of coal from the Lykens collieries made it to market that year. Paired with the economic depression resulting from the Panic of 1873, the Miller family saw their money and standing dwindle. The family seems have to broken apart at this point, with the older brothers leaving the area and heading to Philadelphia.

Charles was forced to forgo his writing career and head west, eventually landing in the area of Hutchinson, Kansas with his wife, Frances Elizabeth Miller and several children. For one reason or another, this venture failed and Dr. Miller attempted to come back to Pennsylvania, possibly to friends in the Lykens area, or further on towards family in Philadelphia. Regardless of his intended destination, Miller never made it past the Allegheny rail yard in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania in the early summer of 1889.

Miller, according to reports, was found beaten and bloodied to nearly the point of unconsciousness in a rail car. Miller later succumbed to his wounds in a Pittsburgh hospital. A coroner’s inquest into the events suggested that foul play was likely in his death and an investigation called, although no suspect or person of interest was never named.

IT WAS MURDER

The Coroner’s inquest on the death of Dr. Charles H. Miller, who died in the West Penn Hospital from wounds received in some mysterious way, was concluded yesterday. He was found, as will be remembered, in a box car on the Allegheny Valley Railroad. The jury’s verdict was that he came to his death from wounds inflicted with a blunt instrument in the hands of persons unknown. Special Officer Edward Fillinger, of the Allegheny Valley Railroad, was censured for not making a more careful investigation of the car in which Dr. Miller was found. Coroner McDowell is confident that it is a clear case of murder; the police think otherwise.

However, several theories were floated through newspapers throughout 1889 and into early 1890. Speculation abounded as to Dr. Miller’s destination on that fateful ride. A New York Times article published in February of 1890 suggested that Dr. Miller succumbed to starvation aboard a locked boxcar and that that was the cause of death. Several other newspapers reported similar stories.

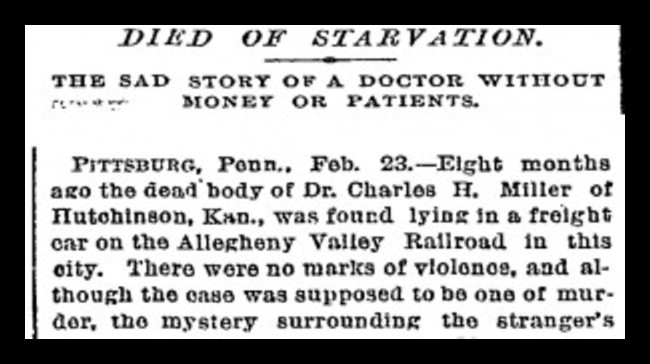

DIED OF STARVATION. The Sad Story of a Doctor Without Money or Patients.

Pittsburg, Penn., Feb. 23.– Eight months ago the dead body of Dr. Charles H. Miller of Hutchinson, Kan., was found lying in a freight car on the Allegheny Valley Railroad in this city. There were no marks of violence, and although the case was supposed to be one of murder, the mystery surround the stranger’s death was never cleared up….

However, this theory runs directly into the testimony of witnesses at the scene, including the rail yard workers who discovered the bloodied Miller. The doctor who first aided Miller was a certain Dr. R. M. Sands, who reported that he “discovered that he had sustained a fracture of the skull and had two ugly gashes above his eyes. It is my opinion that the wounds were made with some blunt instrument.” All of this adds up to a case of sizable intrigue.

Unfortunately, the site of Dr. Miller’s grave is not currently known, but the search continues. The case will never be solved and we are left with the curious details surrounding his unfortunate demise and to surmise what could have befallen him that night in June 1889.

__________________________________________

Corrections and additional information should be added as comments to this post.